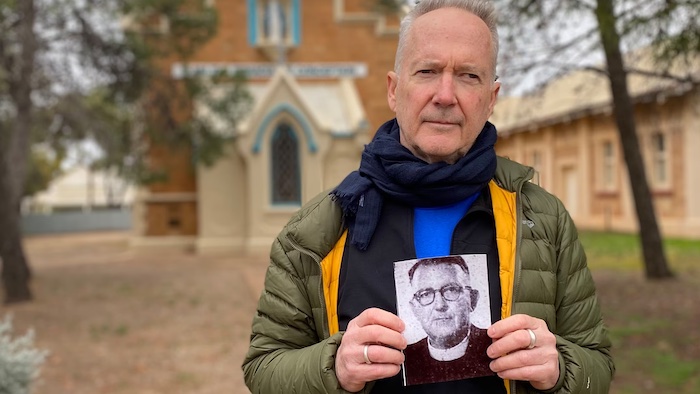

— Brendan Watkins is one of thousands of children of priests who found their biological parents through DNA testing and social media. His birth wasn’t the only secret his father kept.

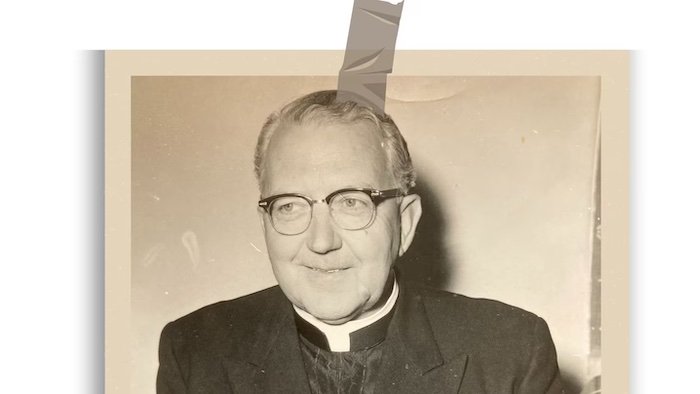

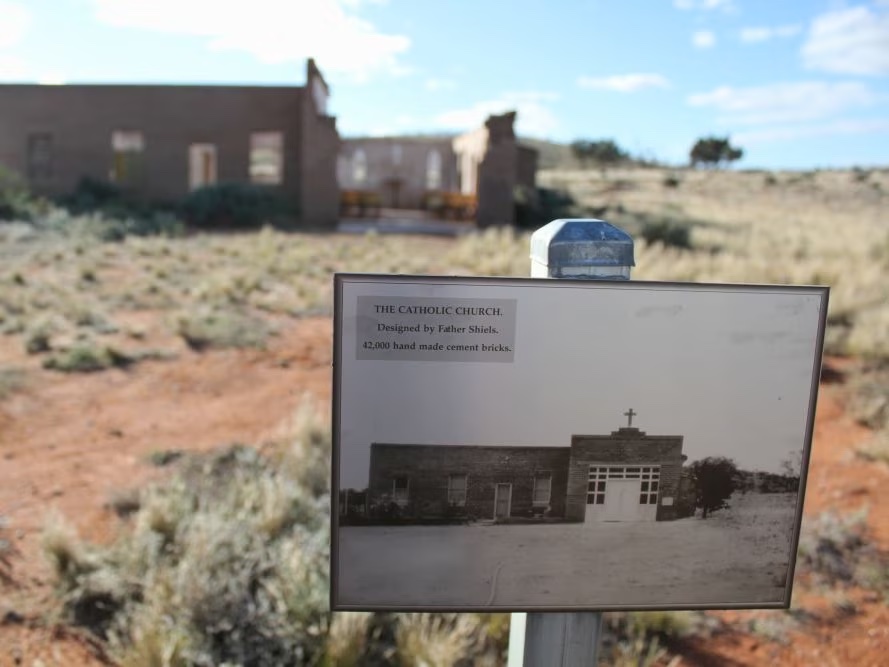

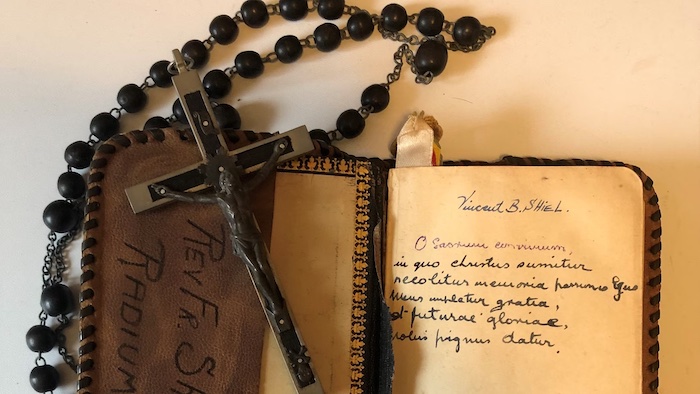

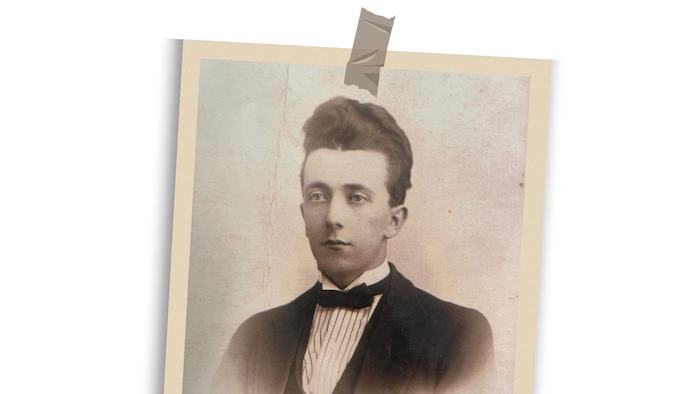

There is a half-crumbling church, covered in red dust, at Radium Hill, a former uranium mine deep in the South Australian desert. It was built by Father Vincent Shiel, with his own hands, in 1956. Six years later, his son Brendan was born in Melbourne to a former nun — a secret the priest kept until he died 37 years later.

Brendan was one of the lucky ones. Both he and his brother Damien were adopted by Roy and Bet Watkins, in Richmond, Melbourne. As Damien, who was adopted two years before Brendan, recalls: “One day a clergyman was talking to Roy and said, ‘Uh, how come you don’t have children yet?’ And Roy said, ‘Well, we haven’t been blessed’. And he said, ‘Maybe that’s something we can help you with’.”

Adoptive brothers Brendan and Damien Watkins in 1962.

Brendan and Damien had an idyllic life with Roy and Bet, who were huge Richmond Tigers fans. They told the boys they were adopted when they were young, but it was Brendan who was most curious about finding his biological parents.

In 1990, at the age of 29, Brendan decided to apply for his original birth certificate because it would carry the names of his biological parents. A meeting was set up at the Catholic Family Welfare Bureau in Melbourne. But it wasn’t what he expected.

“I was hoping that the birth certificate would have both parents’ names,” says Brendan. “It just had my mother’s”. And she wasn’t 16, 17 or 18, as he expected, but much older — 27 — and from South Australia.

Brendan asked the social worker to contact her, but she was reluctant. He was later called back for another meeting. “I was told that I wouldn’t meet my mother, I wouldn’t talk to her,” he says. “And very directly told to go home and forget about her forever. It was the most wounding, impactful trauma of my life.”

A search for answers

Brendan has discovered that globally there are thousands of children of priests, just like him, who as adults found their biological parents through DNA testing and social media groups. There are 450,000 Catholic priests around the world and, though there are no accurate records, it is estimated that they have fathered over 20,000 children.

Crucially, a 25-year study of 1,500 Catholic priests found less than half the priests in the United States attempt celibacy — which experts say is a major factor fuelling so-called reproductive abuse. The study’s author, ex-priest Richard Sipe, argued it creates a culture of secrecy that tolerates and even protects paedophiles — though he estimated that four times as many priests involve themselves sexually with women than with children.

Brendan’s partner Kate did her own research on Brendan’s mother and eventually found one of her relatives. “I recall being at work, and Kate rang and said, ‘Are you sitting down? I found your mother. She’s a nun’, he says. “I pictured my mother in a nun’s habit in a convent walking silently through churches … it gave me some peace.”

But he still had many questions — and was determined to find answers. He eventually made contact with his mother, ‘Maggie’ (not her real name) through letters and a short visit. But who was his biological father? “What followed was essentially 30 years of different stories,” Brendan says. “My father was dead … or she didn’t know what happened to my father.”

Maggie eventually gave Brendan a name, but it turned out to be false. “I wrote back to my mother, and I told her that. And she wrote back and said, ‘Well, I was dumped and so were you’. And she was right … the chase was over.”

Five years later, in 2015, Brendan sent a DNA sample to Ancestry.com.au. Four men came back as possible candidates for his father. One was ruled out. “He was a Catholic priest, so it couldn’t be a Catholic priest. Could it?”

But Brendan’s mother Maggie then confirmed he was indeed the son of Father Vincent Shiel, who died in 1993, at the age of 90. He was still alive when Brendan first contacted Maggie.

But the priest had sworn his mother to secrecy – Brendan says this was a form of spiritual abuse. “It says so much about the misogyny of the Catholic church, the institution,” he says. “It’s a male-centric institution that doesn’t recognise the rights of women. I found that my mother had met my father when she was 14 or 15, and he was 30 years older … so he had enormous influence over her.”

Documents missing, records destroyed

Now he had his father’s real name, Brendan applied to Mackillop Family Services in Melbourne for his file. The archivist couldn’t find any records and told Brendan this was very “unusual”. Brendan had to appeal to the Victorian Department of Justice to receive his file.

“The more children of priests I met and spoke with, I found all sorts of anecdotal stories about destroyed records and people knowing and systems within the church [for] hiding the children of priests and documents going astray,” says Brendan, who was unable to track down his birth records and baptism certificate.

Charlotte Smith, the chief executive of Vanish, an advocacy agency for adopted persons in Victoria, says it’s an “ongoing theme”. “Records have been known to fall off the back of a truck or be destroyed in fires,” she says. “I think it’s really important to investigate what happened. We have quite a few adoptees over the years who have found no paper trail.”

Brendan has spent the last few years writing a book about his adoption journey — Tell No One — published this week. He has made several trips to remote South Australia to find out more about his priest father and the diocese he oversaw. From 1943 to 1977, Father Vincent Shiel lived and worked across a vast area of remote inland towns and coastal cities.

But Brendan’s birth wasn’t the only secret Father Vincent Shiel kept. In 1950, Father Shiel received a call from a doctor from Whyalla Hospital on the Eyre Peninsula. A baby had been born 10 days earlier to a 16-year-old girl who fell pregnant to a farm worker. The problem was, the baby had been left languishing in the ward.

That baby is now 72 years old and lives in Perth.

The right to know

Father Vincent Shiel organised for a young woman to take the baby to Sydney to be brought up by his brother, William Shiel.

Terry grew up the youngest of 10 children. His siblings later told him Father Shiel had sworn them to secrecy. Terry always felt lucky to have such a loving family, and William’s last words to him were: “Just remember, you are my son and you always will be.”

Terry only found out he was adopted in his 30s, when he applied for his birth certificate. It showed he wasn’t officially adopted until he was two years old. He confronted the priest, who was living in the Blue Mountains, and asked for the name of his biological mother.

“I said to him, ‘I found out I was adopted … can you help me out? And I’m trying to track down my birth mother.’ And he sort of shook his head and said … [they’re] probably all dead.”

But Terry’s biological mother wasn’t dead — he eventually met her before she died four years ago — Father Shiel had told him a lie. “I think it’s something that should have been brought out in the open a long, long time ago,” he says. “Everybody has a right to know where they come from … what their background is.”

A global issue

Greens Senator David Shoebridge says Terry’s case raises concerning questions. “These are extraordinary facts that seem to show a national undocumented trade in babies being run by the Catholic Church, says Shoebridge. “But from a systemic level it raises just so many troubling questions about what happened and where the documents now lie.”

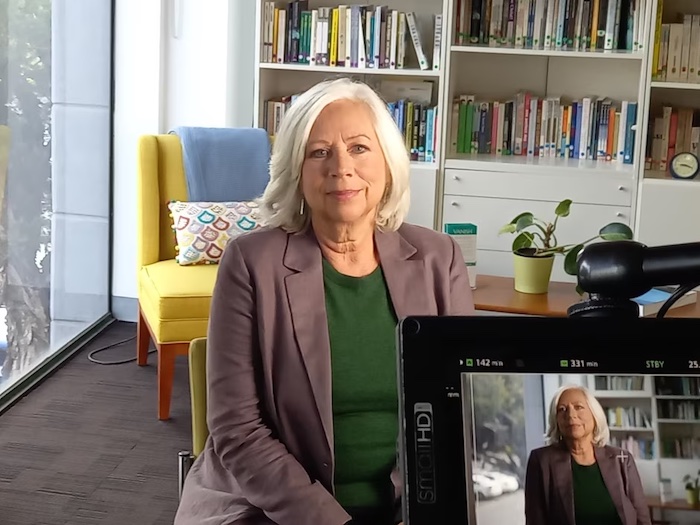

There has never been a global scholarly study on the numbers of children of priests and nuns. But in 2022, Doris Reisinger, a senior academic at the Goethe University in Frankfurt and a former nun published a landmark report on the issue in the United States.

“We are definitely talking hundreds of thousands of children affected by reproductive abuse,” says Dr Reisinger, who has examined thousands of pages of survivor accounts, court documents and newspaper articles. “I found the first abortion case involving a 13-year-old girl. And I found cases with girls even younger than that — 11-year-olds who had become pregnant as a result of sexual abuse by a priest.”

In many cases, Dr Reisinger says, mothers were put under pressure by priests to have abortions or were coerced into hiding, where they’d give birth under “terrible” circumstances.

“I actually think we can assume that this is still going on because none of the contributing factors has been erased,” she says. “The clerical power of priests, mandatory celibacy that often works as a perfect excuse and cover for reproductive abuse — all of that is still fully in place. And no major research has [looked] into reproductive abuse. So there is still lots to be done.”

What DNA evidence reveals

Linda Kelly Lawless is another child of a priest who is seeking official recognition of her ancestry from the Catholic Church through Melbourne Archbishop Peter Comensoli.

Linda’s father Father Joseph Kelly said mass for pregnant unwed mothers who came to the St Joseph’s Receiving Home in Carlton to have their babies and adopt them out. Linda says he was having an affair with her mother at the same time – she was not at the home.

“Only a few months later he was actually using the adoption system to get rid of me, which happened the following year,” she says. “And when I was born … my paperwork was never finished and … seemed to vanish from this hospital. All my paperwork has ‘baby for adoption’, false names, I can’t find my baptism records.”

Over the last five years, Linda has met with Archbishop Comensoli and presented him with many documents, including DNA reports and affidavits from family members. But Archbishop Comensoli said while he personally believed she was the daughter of Father Joseph Kelly, any formal recognition would need to come from the state, not the church.

Linda engaged the US company Parabon, which is used by the FBI and Queensland Police Service in criminal and missing persons cases. “I had legal DNA testing with Parabon in America, and a cousin from my grandfather’s side and a cousin from my grandmother’s side set forward,” she says .“The results came back that I was 99 per cent related to both of them.”

Linda presented the results to Archbishop Comensoli. In April this year, she received a letter in response in which he suggested an exhumation of Father Joseph Kelly’s body would be necessary in order for the Catholic church to officially recognise Kelly has her father. He wrote:

“In saying this, I must be very clear that I cannot state categorically that he is your biological father. There is simply not the level of information to do so. You have provided significant evidence of a shared heritage, but it directly doesn’t lead to a singular person … I again note that although I do not have the authority to request an exhumation of Father Joseph Kelly, if it is to be sought, it would need to come from you. I would be prepared to support such an application from your yourself.”

In a statement, Archbishop Comensoli told Compass that the Archdiocese of Melbourne has “supported Linda … and have offered financial support”:

“There is no denying the historical fact that priests have fathered children. The church now steps forward in finding ways to acknowledge children who have priests as their father.

“I cannot state categorically that Fr Kelly is her biological father — there is simply not the level of information to do so at this point in time.

“Regardless of the above, I have shared with Linda in writing that I believe that Fr Kelly is her biological father.”

Linda says she will consider exhumation if that is what it takes to get official recognition from the Catholic Church.

The cemetery where her father is buried has allowed her to take ownership of his plot and put her name on the headstone. “I now actually own my father’s and grandfather’s grave in the private Catholic cemetery,” she says. “They seem to believe my evidence and DNA was enough to show that he was my father.”

She says she is not seeking legal compensation: “I’ve asked for a letter of recognition that they acknowledge that he’s my father. I asked for some support to sort out my birth certificate because it’s not finished. I don’t have a surname, which they have helped me with. I asked for an apology for my mother.”

An inquiry for truth and justice

Vanish, the peak adoption advocacy group in Victoria, is calling for an independent public inquiry into the treatment of the children of priests and their mothers.

“It’s clearly the case that he’s the father and it would appear that since they’re not accepting responsibility, that an inquiry is required to push that,” says Charlotte Smith. A public inquiry would help shed light on how many children have been fathered by priests, she adds, and provide victims and survivors with “some sort of justice”.

Dr Reisinger agrees: “We need an independent inquiry with a strong political backing and with thorough scholarly experience to look into this.”

Federal Greens Senator David Shoebridge wants a federal inquiry. “There clearly needs to be an inquiry which has the power to compel the truth out of the church,” he says.

“We cannot leave these people who were literally stolen at birth by the church to do this fight alone. This is a matter that I think needs to be closely considered by the Federal Attorney General and by the federal government — the fact that it was happening all over the country and the fact that these children were moving across borders.”

Brendan Watkins wants an inquiry to also look at the church’s treatment of the mothers.

“In truth, there’s probably thousands of women like my mother, who live with enormous shame and guilt,” he says. “And they suffer.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!