— A former diocese organist filed suit in February 2022. Some laity and priests are unhappy with Stika’s staunch defense of a seminarian accused of rape.

By John North

Knoxville Catholic Bishop Richard Stika is facing increasing criticism and scrutiny over his leadership, including how he’s handled accusations that a former seminarian raped a church musician, newly gathered documents show.

The musician is suing Stika and the Catholic Diocese of Knoxville in Knox County Circuit Court. Judge Jerome Melson is expected to hold a hearing Friday for the musician’s lawyers and diocesan attorneys.

The hearing comes as local and national attention grows about the diocese, the boundaries of which stretch from Chattanooga to Knoxville and on up to the Tri Cities. An online publication called The Pillar has published numerous stories critical of Stika’s leadership since 2021.

Complaints against him gained even greater prominence May 11 when the National Catholic Reporter published a lengthy story about the bishop and his leadership.

WBIR previously has reported about the ex-organist’s February 2022 lawsuit as well as a federal complaint filed in November 2022 against the diocese by a Honduran woman who alleges a Gatlinburg priest sexually battered her.

In recent weeks, however, numerous internal documents including emails, reports and handwritten notes from 2021 and 2022 have surfaced as the organist’s lawsuit slowly advances through the legal system.

They show priests in the Knoxville Diocese expressing increasing complaints about Stika, 65, and his handling of a rape allegation made against the Polish seminarian. They’ve been baffled by his persistent support of the seminarian, records show.

Many of the documents appear to serve as the basis or source of allegations in the musician’s February 2022 lawsuit, which alleges defamation and negligence. The organist is suing the diocese and Stika; he is not suing the seminarian.

Records and two secret audio recordings from 2021 also show Stika steadfastly defending the now former seminarian and at times scolding and criticizing those who have questioned him.

“Bishop Stika has a history of intimidating people he does not agree with or like,” one priest wrote in October 2019 as tensions mounted within the diocese.

“We humbly ask for appointment of a new Bishop who we can believe in, put our faith in, and who can appropriately guide us in our Catholic lives,” a 2022 petition on change.org from a lay member and Chattanooga area attorney states.

Appointed in 2009 to come to Knoxville, the bishop previously has told priests that he is staying right where he is.

“I ain’t going anywhere,” Stika told the men during a meeting May 25, 2021, after controversy over the Polish seminarian arose. “I haven’t done anything wrong.”

In May, three priests in the diocese also met with WBIR to express their concerns.

The diocese said it could not comment because of the ongoing litigation.

HOW IT STARTED

The organist worked in the diocese from 2015 until August 2019.

WBIR is not naming him because he alleges he is a rape victim. WBIR is not naming the former seminarian — whose name is widely known within the diocese — because he has not been charged with a crime.

In January 2019, the freshly arrived seminarian struck up a friendship with the organist.

According to the lawsuit, the musician alleges the seminarian sought a sexual relationship. He states in his complaint that he was “pressured into brief sexual touching and oral sex on isolated occasions. Plaintiff did not feel particularly attracted to (the seminarian) and was not interested in a sexual relationship with someone so forceful and aggressive.”

The Polish man would at times forcefully kiss the organist, the lawsuit alleges.

The organist is seven years older than the seminarian, Stika has said.

The seminarian wanted to keep his physical relationship with the musician secret, according to the lawsuit.

According to the complaint, the musician kept up his association with the Polish man “because he felt bad for him as a gay seminarian.” He also alleges he felt obliged to stay on good terms because the seminarian had a close relationship with Stika, who had taken him in. Stika has said the seminarian came recommended by the late Pope John Paul II’s personal secretary in Poland.

On Feb. 5, 2019, the organist alleges, the seminarian came on to him aggressively, pinned him down and raped him to the point that he suffered bleeding.

The musician alleges he went to bed that night “in shock and pain” and that the seminarian spent the night with him in bed.

Five days later, the seminarian left a Catholic prayer book for the organist with an inscription of well wishes from Stika. Four days later — Valentine’s Day — the Polish man handed him a card and a bottle of Champagne. In the card he expressed thanks for his friendship and added, “And for what was wrong — I apologize with all my heart.”

According to the lawsuit, the musician went to the Knoxville Police Department on Feb. 25, 2019, to report the rape. But the lawsuit states that a KPD officer told him if he pursued the criminal case the church would “come after” him and he’d lose his job. It would be his word against the seminarian’s, the plaintiff says he was told.

No rape charge was ever filed.

The musician alleges he tried to avoid the seminarian but the Polish man “stalked” him.

On March 29, 2019, some six weeks after the alleged rape, the two young men had dinner at a restaurant with Stika. Because of Stika’s position as bishop, the musician alleges he felt he had little choice but to go along with the dinner.

A photo — submitted with the lawsuit — was taken of the trio, with Stika on one side of the table and the two younger men on the other.

“At the end of dinner, Stika asked (the organist) if he ever had any trouble with his co-workers,” the lawsuit states. “(The musician) felt constrained to answer no, given (the Polish man’s) relationship with the bishop.”

In August 2019, six months after the alleged rape, the musician moved on to Atlanta. He filed his lawsuit 18 months later in Knox County.

During 2019, the seminarian lived at Stika’s West Knox County house along with retired Cardinal Justin Rigali, a longtime mentor of Stika’s. The seminarian drove the older men around as needed. Stika would later say — at a 2021 meeting secretly recorded in Knoxville — that he’d lost sight in one eye and didn’t trust his driving.

The seminarian also traveled with Stika and Rigali, including joining them on a trip to the Vatican.

In the fall of 2019, the seminarian went off to Saint Meinrad seminary school in Indiana. By early 2021, however, he’d been dismissed, records reviewed by WBIR show.

Some of his fellow seminarians in Indiana reported that he’d touched them inappropriately or acted inappropriately around them.

In one encounter in January 2021, he tickled and grappled with a student who was visiting Tennessee from out of town. He also sent unwanted and invasive Snapchat messages about his penis, documents reviewed by WBIR state.

Another seminarian reported that while at Saint Meinrad in February 2021, he caught the Polish man spying into his room from across the courtyard.

The seminarian was dismissed from the Indiana school that month, an email shows.

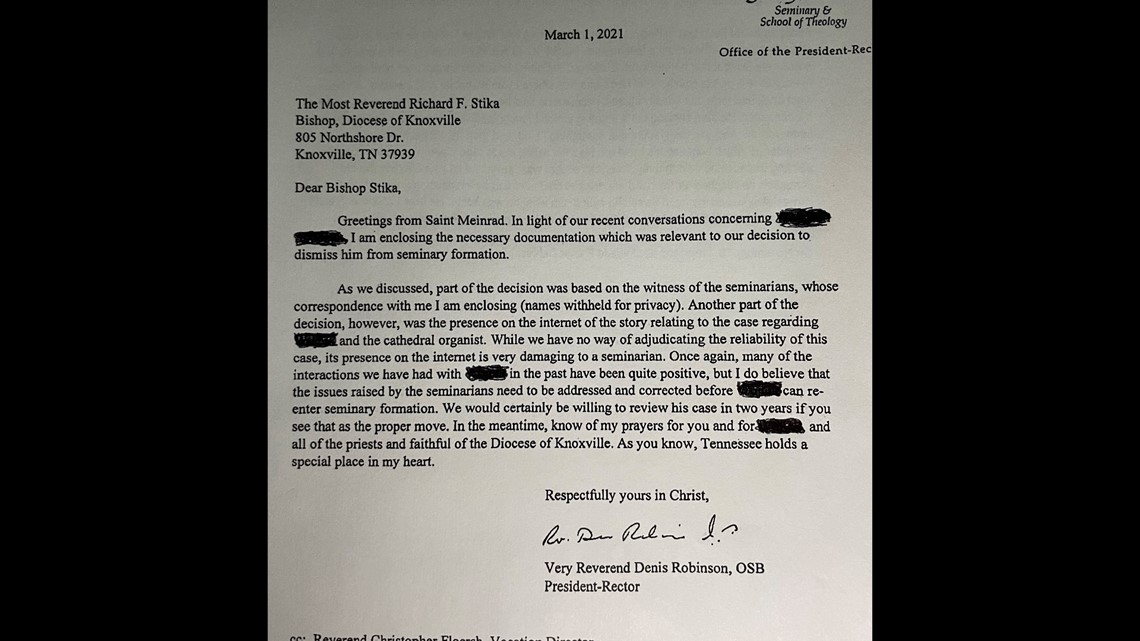

On March 1, 2019, Meinrad President-Rector the Very Rev. Denis Robinson wrote Stika that the school had decided to dismiss the Polish man because of what his fellow students had experienced and also because of online accusations that had emerged about the 2019 alleged rape.

“While we have no way of adjudicating the reliability of this case, its presence on the internet is very damaging to a seminarian,” Robinson wrote. “Once again, many of the interactions we have had with (the Polish man) in the past have been quite positive, but I do believe that the issues raised by the seminarians need to be addressed and corrected before (the Polish man) can re-enter seminary formation.”

In two years’ time, Robinson wrote, they’d be willing to review his case “if you (Stika) see that as a proper move.”

A QUICK INVESTIGATION

Emails, notes, reports and the two audio recordings from spring 2021 show rising skepticism, even anger, about the way the bishop handled the Polish seminarian.

Reports about the man’s conduct with the organist began circulating in the diocese in early 2021.

On Feb. 26, 2021, after dismissal from Saint Meinrad, Stika sent a note to priests in the diocese stating that the seminarian had entered a “two-year period of discernment,” meaning he would be reflecting on what God wanted him to do. He wrote that the man would be helping him in the Chancery in Knoxville and helping the octogenarian Cardinal Rigali.

His note offended some priests in light of allegations about the seminarian’s aggressive, sexual conduct, documents show. Priests complained Stika was giving him special treatment.

A formal investigation was needed, one priest wrote. Furthermore, he wrote, Stika needed to be held accountable.

A March 11, 2021, email from the bishop to an attorney and senior members of the diocese stated, “I have informed the individual of his need to return home. I am working with his former school on when this would be necessary.”

Any assumption that the Polish man would be sent home to Eastern Europe, however, proved false. Instead, Stika sought to have him go off to Saint Louis University in St. Louis, Mo., Stika’s alma mater and hometown, to enroll at the diocese’s expense, a letter shows.

Carleton E. “Butch” Bryant, a church member and former staff attorney for the Knox County Sheriff’s Office, notified Stika and members of the diocese’s internal Diocesan Review Board that he was calling a March 25 meeting to consider whether they should formally investigate allegations against the seminarian, records show.

The board is a “confidential consultative body” to the bishop, according to the diocese.

An investigation was indeed launched, with George Prosser, a former Tennessee Valley Authority inspector general, tapped to do the investigative footwork.

Stika, however, as he would later say at a May 2021 meeting with area priests, didn’t like the way Prosser conducted the inquiry. He asked questions that confused and upset people in the diocese, he said. Prosser was a nice man, he’d say later, a 75-year-old neighbor, but he wasn’t the man to handle the investigation.

He removed Prosser.

Diocesan Review Board member Christopher J. Manning took Prosser’s place.

Manning’s report shows he interviewed the Polish seminarian April 16, 2021. He did not talk with the former church organist or the students in Indiana at Saint Meinrad.

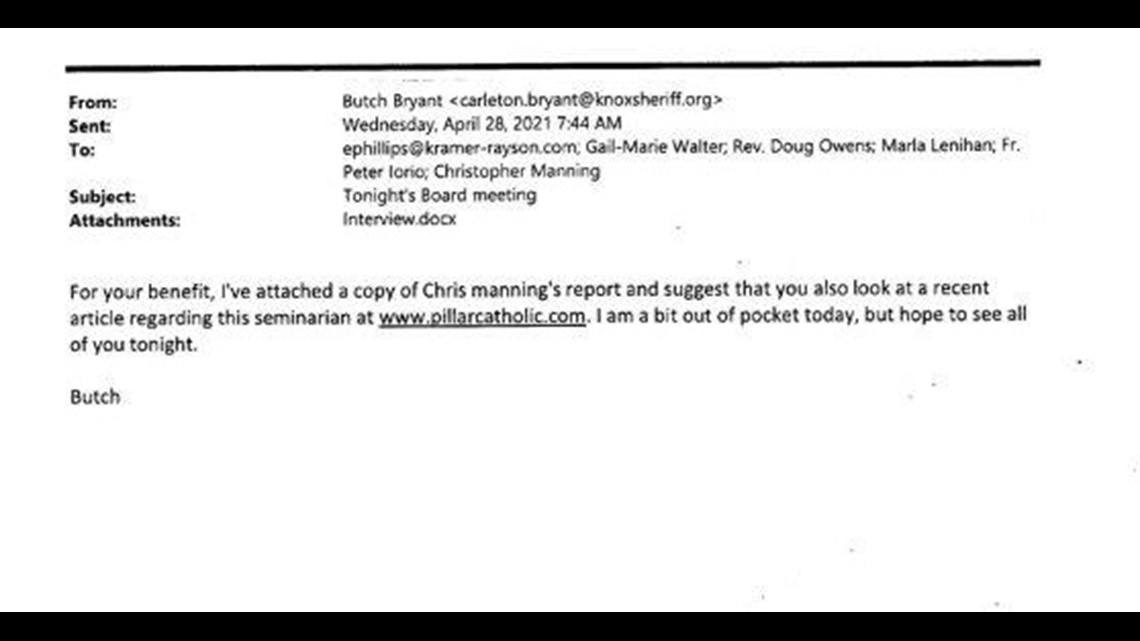

Three days before, however, Bryant sent an email to members of the Diocesan Review Board stating that Stika had informed him the investigation “is closed.” They could all talk about it at an upcoming meeting later that month, Bryant’s email states.

After his interview, Manning prepared an April 16, 2021, report for Stika, Bryant and Vicar-General Doug Owens.

In his interview, the seminarian said he’d been friends only with the musician and that there’d not been mutual sex. He said the musician told him he was gay, the report states.

He alleged that the musician initiated sex with him during a trip in late January or early February to Atlanta, Manning’s report states. The seminarian said he resisted the overture. The seminarian told Manning they shared a king-size bed in Atlanta and that the musician tried to perform oral sex in the middle of the night.

The pair traveled to Las Vegas and the Grand Canyon in May 2019, according to Manning’s report. While in their Las Vegas hotel, the seminarian claimed he saw the musician and a young Hispanic man kiss and have sex.

In June 2019, according to his conversation with Manning, the seminarian said the musician told him he was moving to Atlanta. They had dinner and the musician gave him a shirt as a gift, the report states.

The seminarian denied any inappropriate conduct with the men at the Indiana seminary school, the report states.

“There is no indication that Mr. ——— was untruthful during this interview. He did not hesitate (sic) any of the questions and provided specific details when those were requested,” Manning wrote.

Bryant sent the Manning report to the Diocesan Review Board on April 28 ahead of that night’s meeting. Emails show some in the diocese strongly disagreed with the conclusion of the investigation and lack of action against the seminarian. It was one-sided, they said.

One priest wrote that Stika had impeded the investigation. He wrote that the bishop had a history of “intimidating” people who disagree with him, records show. The bishop had even threatened to resign because he thought it wrong to send the seminarian back to Poland, according to the priest.

In a letter dated April 12, 2021, four days before Manning talked with the Polish seminarian, Stika wrote “To Whom It May Concern” at Saint Louis University that the Knoxville Diocese would cover room, board and tuition for the seminarian in the amount of $48,258 for the fall 2021 school year.

“(He) will not in any way be a burden to the United States of America or the State of Tennessee,” the letter stated.

‘DRIP, DRIP, DRIP’

Stika addressed priests in the diocese in meetings in May and June 2021. A priest recorded the gatherings, and they’ve now become part of the allegations contained in the organist’s lawsuit.

The meetings came soon after another critical online piece by The Pillar.

The bishop told the men he regretted having invited The Pillar to come to Knoxville and see the work of the diocese for itself. He warned against speaking to the media because the priests wouldn’t be able to control that outcome.

“He (The Pillar writer) doesn’t care about us. He just wants to sell subscriptions,” Stika said in the June 8, 2021, meeting. “He moves on, and here we are.”

He told the men he believed the musician was the sexual aggressor, not the Polish seminarian.

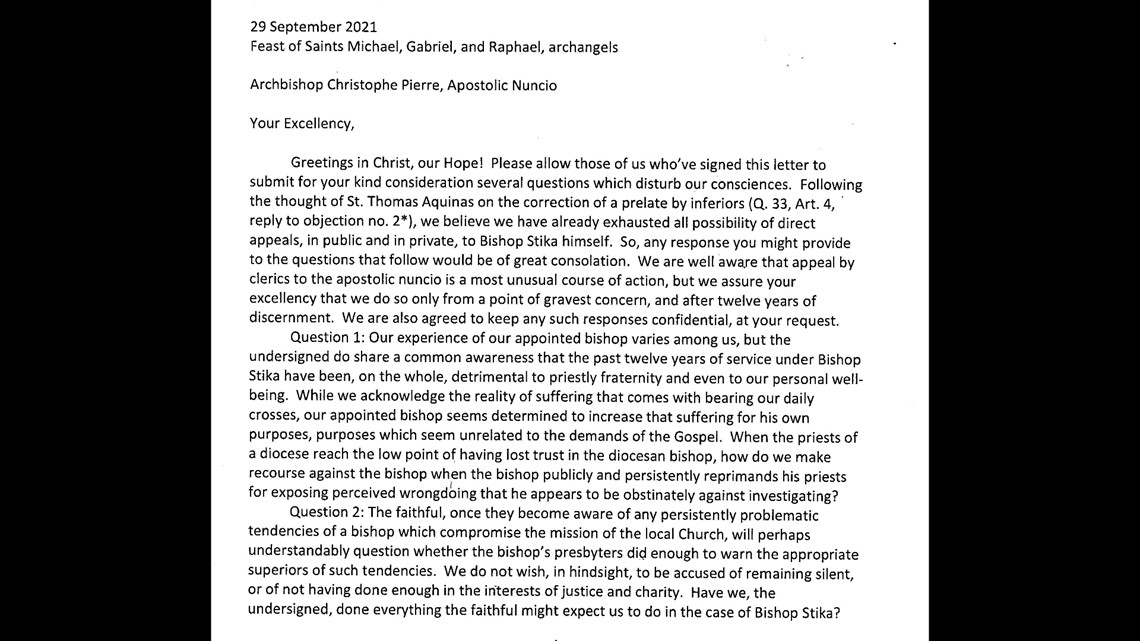

By September, some priests in the diocese had begun putting together a letter seeking action by Archbishop Christophe Pierre, the apostolic nuncio in Washington, D.C. They expressed their reservations about Stika’s leadership. The nuncio acts as a liaison and formal representative of the pope.

Multiple priests signed the letter sent to Pierre. They did not get a response, according to three priests who asked that their names be withheld to avoid possible retaliation.

A Vatican investigative team did end up traveling to Knoxville and interviewing various people, according to the priests and several Catholic media reports. But there’s been no obvious action.

In addition, records show, respected priest Father Brent Shelton quietly drafted an email to Stika, circulated among various priests, that questioned him about the church investigation and what Stika was doing to serve the diocese. Shelton ended up leaving the diocese this spring after Stika proposed moving him from his Oak Ridge church.

The “drip, drip, drip” of new allegations was worrisome, the draft email circulated among some priests states.

“We are losing parishioners; parents are questioning whether to entrust their children to our schools and we are given little guidance into how this matter is progressing and when and how it will end,” the email stated.

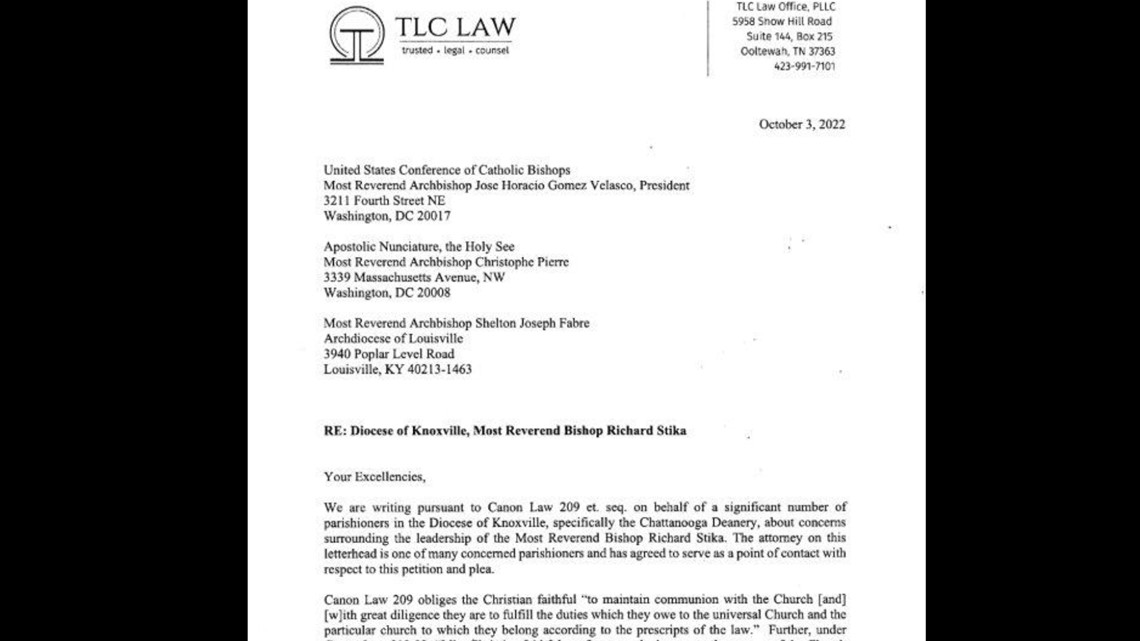

In October 2022, Chattanooga area attorney and lay diocese member Theresa Critchfield also prepared a letter on her TLC Law stationery about Stika’s leadership. It was uploaded as a petition to change.org.

The Oct. 3, 2022, letter was directed to Pierre in Washington as well as Jose Horacio Gomez Velasco, the president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, and to the Rev. Shelton J. Fabre, the archbishop of Louisville, which presides over the Knoxville Diocese.

According to the letter, members of the Chattanooga Deanery had lost faith in Stika “as our shepherd.” The letter cited among other things church finances and Stika’s handling of the seminarian’s time in Knoxville.

LINGERING QUESTIONS

There’s been little movement with the organist’s lawsuit since it was filed in February 2022.

Judge Melson has granted the defendants’ request that the organist amend his lawsuit to identify himself by name rather than as “John Doe”. The amended complaint was filed in January.

The former seminarian moved to St. Louis and is believed to still live there, according to the three priests.

On May 11, the independent National Catholic Reporter, which has reported for decades on the church, published a lengthy story that included an interview with Stika, Critchfield and unnamed priests, among others. The story detailed multiple concerns among parishioners and priests about the state of the diocese. It reported some in Knoxville feel “demoralized” by the ongoing turmoil.

Stika told the newspaper he didn’t practice retribution. He said he also saw great progress across the diocese, which has some 70 priests and more than 70,000 parishioners.

“I see growth, I see financial stability, I see vocations and I see happiness,” he told the paper.

The organist’s lawsuit is the second to challenge Stika’s leadership in recent years. A complaint filed in November 2022 on behalf of a Honduran woman alleges she was sexually battered by priest Antony Punnackal in 2020 inside a Gatlinburg church.

The federal lawsuit names the diocese, Punnackal and the Carmelites of Mary Immaculate as defendants.

The complaint also alleges the diocese tried to discredit her and to silence her when she began making accusations against Punnackal. The complaint is on hold while a criminal case against the priest proceeds in Sevier County Circuit Court.

Punnackal was removed from active ministry in January 2022, according to the diocese. He appeared earlier this month at a court hearing in his case in Sevier County.

The sexual battery trial is set for September.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!