by DAVID CRARY

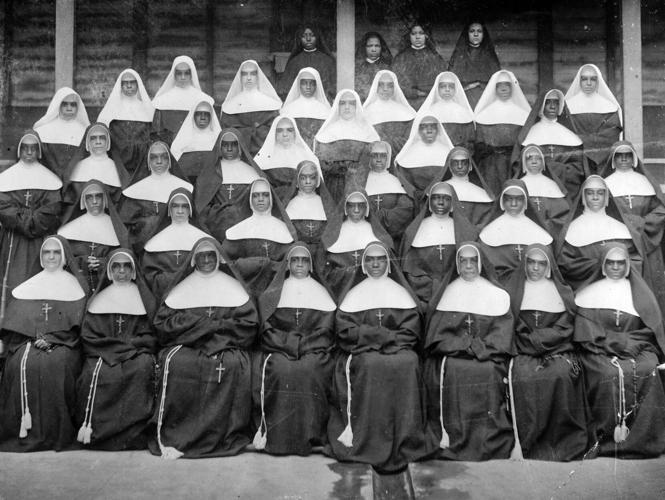

Even as a young adult, Shannen Dee Williams – who grew up Black and Catholic in Memphis, Tennessee – knew of only one Black nun, and a fake one at that: Sister Mary Clarence, as played by Whoopi Goldberg in the comic film “Sister Act.”

After 14 years of tenacious research, Williams – a history professor at the University of Dayton – arguably now knows more about America’s Black nuns than anyone in the world. Her comprehensive and compelling history of them, “Subversive Habits,” will be published May 17.

Williams found that many Black nuns were modest about their achievements and reticent about sharing details of bad experiences, such as encountering racism and discrimination. Some acknowledged wrenching events only after Williams confronted them with details gleaned from other sources.

“For me, it was about recognizing the ways in which trauma silences people in ways they may not even be aware of,” she said.

The story is told chronologically, yet always in the context of a theme Williams forcefully outlines in her preface: that the nearly 200-year history of these nuns in the U.S. has been overlooked or suppressed by those who resented or disrespected them.

“For far too long, scholars of the American, Catholic, and Black pasts have unconsciously or consciously declared — by virtue of misrepresentation, marginalization, and outright erasure — that the history of Black Catholic nuns does not matter,” Williams writes, depicting her book as proof that their history “has always mattered.”

The book arrives as numerous American institutions, including religious groups, grapple with their racist pasts and shine a spotlight on their communities’ overlooked Black pioneers.

Williams begins her narrative in the pre-Civil War era when some Black women – even in slave-holding states – found their way into Catholic sisterhood. Some entered previously whites-only orders, often in subservient roles, while a few trailblazing women succeeded in forming orders for Black nuns in Baltimore and New Orleans.

Even as the number of American nuns – of all races – shrinks relentlessly, that Baltimore order founded in 1829 remains intact, continuing its mission to educate Black youths. Some current members of the Oblate Sisters of Providence help run Saint Frances Academy, a high school serving low-income Black neighborhoods.

Some of the most detailed passages in “Subversive Habits” recount the Jim Crow era, extending from the 1870s through the 1950s, when Black nuns were not spared from the segregation and discrimination endured by many other African Americans.

In the 1960s, Williams writes, Black nuns were often discouraged or blocked by their white superiors from engaging in the civil rights struggle.

Yet one of them, Sister Mary Antona Ebo, was on the front lines of marchers who gathered in Selma, Alabama, in 1965 in support of Black voting rights and in protest of the violence of Bloody Sunday when white state troopers brutally dispersed peaceful Black demonstrators. An Associated Press photo of Ebo and other nuns in the march on March 10 — three days after Bloody Sunday — ran on the front pages of many newspapers.

During two decades before Selma, Ebo faced repeated struggles to break down racial barriers. At one point she was denied admittance to Catholic nursing schools because of her race, and later endured segregation policies at the white-led order of sisters she joined in St. Louis in 1946, according to Williams.

The idea for “Subversive Habits” took shape in 2007, when Williams – then a graduate student at Rutgers University – was desperately seeking a compelling topic for a paper due in a seminar on African American history.

At the library, she searched through microfilm editions of Black-owned newspapers and came across a 1968 article in the Pittsburgh Courier about a group of Catholic nuns forming the National Black Sisters’ Conference.

The accompanying photo, of four smiling Black nuns, “literally stopped me in my tracks,” she said. “I was raised Catholic … How did I not know that Black nuns existed?”

Mesmerized by her discovery, she began devouring “everything I could that had been published about Black Catholic history,” while setting out to interview the founding members of the National Black Sisters’ Conference.

Among the women Williams interviewed extensively was Patricia Grey, who was a nun in the Sisters of Mercy and a founder of the NBSC before leaving religious life in 1974.

Grey shared with The Associated Press some painful memories from 1960, when – as an aspiring nurse – she was rejected for membership in a Catholic order because she was Black.

“I was so hurt and disappointed, I couldn’t believe it,” she said about reading that rejection letter. “I remember crumbling it up and I didn’t even want to look at it again or think about it again.”

Grey initially was reluctant to assist with “Subversive Habits,” but eventually shared her own story and her personal archives after urging Williams to write about “the mostly unsung and under-researched history” of America’s Black nuns.

“If you can, try to tell all of our stories,” Grey told her.

Williams set out to do just that – scouring overlooked archives, previously sealed church records and out-of-print books, while conducting more than 100 interviews.

“I bore witness to a profoundly unfamiliar history that disrupts and revises much of what has been said and written about the U.S. Catholic Church and the place of Black people within it,” Williams writes. “Because it is impossible to narrate Black sisters’ journey in the United States — accurately and honestly — without confronting the Church’s largely unacknowledged and unreconciled histories of colonialism, slavery, and segregation.”

Historians have been unable to identify the nation’s first Black Catholic nun, but Williams recounts some of the earliest moves to bring Black women into Catholic religious orders – in some cases on the expectation they would function as servants.

One of the oldest Black sisterhoods, the Sisters of the Holy Family, formed in New Orleans in 1842 because white sisterhoods in Louisiana, including the slave-holding Ursuline order, refused to accept African Americans.

The principal founder of that New Orleans order — Henriette Delille — and Oblate Sisters of Providence founder Mary Lange are among three Black nuns from the U.S. designated by Catholic officials as worthy of consideration for sainthood. The other is Sister Thea Bowman, a beloved educator, evangelist and singer who died in Mississippi in 1990 and is buried in Williams’s hometown of Memphis.

Researching less prominent nuns, Williams faced many challenges – for example tracking down Catholic sisters who were known to their contemporaries by their religious names but were listed in archives by their secular names.

Among the many pioneers is Sister Cora Marie Billings, who as a 17-year-old in 1956 became the first Black person admitted into the Sisters of Mercy in Philadelphia. Later, she was the first Black nun to teach in a Catholic high school in Philadelphia and was a co-founder of the National Black Sisters’ Conference.

In 1990, Billings became the first Black woman in the U.S. to manage a Catholic parish when she was named pastoral coordinator for St. Elizabeth Catholic Church in Richmond, Virginia.

“I’ve gone through many situations of racism and oppression throughout my life,” Billings told The Associated Press. “But somehow or other, I’ve just dealt with it and then kept on going.”

According to recent figures from the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, there are about 400 African American religious sisters, out of a total of roughly 40,000 nuns.

That overall figure is only one-fourth of the 160,000 nuns in 1970, according to statistics compiled by Catholic researchers at Georgetown University. Whatever their races, many of the remaining nuns are elderly, and the influx of youthful novices is sparse.

The Baltimore-based Oblate Sisters of Providence used to have more than 300 members, according to its superior general, Sister Rita Michelle Proctor, and now has less than 50 – most of them living at the motherhouse in Baltimore’s outskirts.

“Though we’re small, we are still about serving God and God’s people.” Proctor said. “Most of us are elderly, but we still want to do so for as long as God is calling us to.”

Even with diminished ranks, the Oblate Sisters continue to operate Saint Frances Academy – founded in Baltimore by Mary Lange in 1828. The coed school is the country’s oldest continually operating Black Catholic educational facility, with a mission prioritizing help for “the poor and the neglected.”

Williams, in an interview with the AP, said she was considering leaving the Catholic church – due partly to its handling of racial issues – at the time she started researching Black nuns. Hearing their histories, in their own voices, revitalized her faith, she said.

“As these women were telling me their stories, they were also preaching to me in a such a beautiful way,” Williams said. “It wasn’t done in a way that reflected any anger — they had already made their peace with it, despite the unholy discrimination they had faced.”

What keeps her in the church now, Williams said, is a commitment to these women who chose to share their stories.

“It took a lot for them to get it out,” she said. “I remain in awe of these women, of their faithfulness.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!