Ireland’s Catholic bishops have been too slow to address the problems of a clericalised Church and a laity that often feels disconnected or is absent altogether.

by

“WE have a lot of priests in Ireland who are in their seventies, who are working right now. Some are in their eighties… We’re at the edge of an actuarial cliff here, and we’re going to start into a free fall.”

So said the Pope’s representative in Ireland, Archbishop Charles Brown, in March 2017. Back then it was still possible to believe that Irish bishops could reappraise a clericalised Church system that has scandalised most Irish people – and left many unanswered questions for those who still go to Church.

By the summer of 2019, however, it seems that not even a majority of Irish bishops has absorbed the most important lessons of the scandals that began in Ireland in 1992.

Though Pope Francis is allowing Brazil’s bishops to consider the ordination of mature married men, most Irish bishops still apparently believe that Irish Catholic families must somehow be persuaded to encourage their young people to head for seminaries and convents and celibate lives.

Consider, for example, To Follow Jesus Closely, a pastoral letter published in the Diocese of Down and Connor in April 2019, and covered extensively in Faith matters.

It tells us that young people cannot do without the ordained celibate priest to “reassure them that life does make sense, that there is a God who loves them, and that in the end, all will be well”.

Given that this is basic Christian wisdom – and that ordained priests can also suffer from depression, addiction and loss of faith – what does this assert about the Christian competence, gifts and potential of Irish Catholic lay people, parents especially?

In all but one instance the word “priest” is used in this document to denote solely the ordained priest.

Only once are we reminded that by baptism all Christians – including all teenagers – already also have a priestly calling; but here again, according to the pastoral letter, only the seminary-trained priest can explain this to us.

Otherwise we would never know how to exercise “faithfully and fully the common priesthood… received in baptism”.

Nowhere in this document is the role of this “common priesthood” – the priesthood of all of the faithful – explained.

This does not surprise me. In over seven decades of Massgoing I have never heard an Irish diocesan priest express the slightest interest in it.

The word ‘priest’ derives from the Latin ‘pontus’ – a bridge – so a ‘priest’ in the religious sense is one whose calling is to bridge for others the distance between themselves and God.

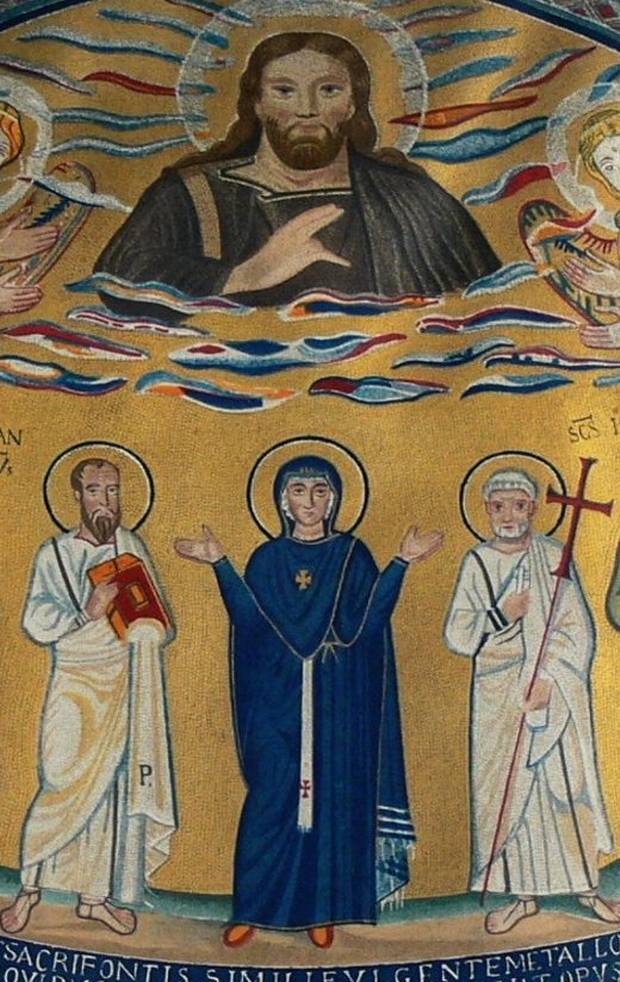

The priesthood of Jesus was unique in the ancient world. He not only initiated the sacred Christian sacrificial ritual – the Eucharist – but he was also himself the sacrificial gift, in his surrender to judgement and crucifixion.

According to the Gospels, Jesus had provoked his own crucifixion by challenging an abusive religious system that privileged the well-to-do and therefore distanced the poorest from God.

It follows that all of us Catholics are called not only to attend Mass but to offer ourselves in that same cause – the closing of the distance between the poorest and God, a distance obviously growing in Ireland.

Members of the St Vincent de Paul and of other Catholic charities are therefore faithfully exercising their priestly calling, as are all who answer the call to social justice and to service of the needy.

And so were those Catholic parents who blew the whistle on the most devastating spiritual abuse ever perpetrated against Irish Catholic children – sexual abuse by professedly celibate Catholic ordained clergy.

In exercising the most elemental duty of a Christian parent – the protection of the child’s right to believe in their own sacred dignity – those parents were protesting against the abuse of that right by ordained men, a possibility they had never been warned about by their bishops.

In many cases those parents then suffered what Jesus suffered – isolation within their own communities.

Have the bishops taken time to consider what ‘help’ those parents had ever received from ordained clergy in understanding and exercising their Christian duty – their priesthood – in that way?

Do they remember that Irish bishops first gave priority to the cause of protecting Catholic children from clerical abuse only in 1994 – at precisely the moment that the whole island first learned, from those injured parents – and that Irish bishops had until that very moment given a higher priority to the sheltering of abusive priests?

Other obvious questions follow:

- If criminally abusive breaches of priestly celibacy did not bar ordained men from celebration of the Eucharist in Ireland until those breaches were publicly known, why is Christian marriage still a barrier to that ordained Eucharistic role in Ireland?

- Why should a religious life deliberately sundered from any parental role continue to have higher status in the Church than the witness of married lives of integrity – especially those of mothers whose self-sacrificing love, as Pope Francis has observed, is indeed often the best witness a child will ever have of the Father’s unconditional love?

- If the ordained priest is indeed best placed to help lay people to understand their common priesthood, why has Catholic social teaching always been a closed book for most diocesan clergy in Ireland?

- From Confirmation on, why can young people expect to be bored rigid at Mass, instead of reminded of their own priesthood and challenged to pray to the Holy Spirit for the courage, wisdom and whatever other spiritual gifts are needed to meet together the dangers of their young lives – everything from schoolyard bullying, substance abuse, internet trolling and climatic collapse to media celebrity culture, institutional corruption, sexual harassment and white supremacist ideology?

- Why have Irish bishops not yet initiated and published reliable research into the reasons for the widescale abandonment of religious practice here, especially among the young, by the Irish majority that still identifies as Catholic?

- Why are there still no regular opportunities to raise such questions openly in Irish Catholic parishes and dioceses, when they could be asked by any alert teenager contemplating a life calling?

- If seminaries are truly the best places to train men to be ‘in persona Christi’, why was no Catholic bishop anywhere in the world a whistleblower against clerical child abuse before parents and victims had to act?

To Follow Jesus Closely suggests that some Irish bishops believe that Catholic parents and grandparents have no access to reliable news media, no powers of observation or reflection, no memory, no access to the many gifts of the Holy Spirit and – after all that has happened in their own lifetimes – no such questions.

And it might also suggest that Irish teenagers who can qualify for university are naïve when it comes to recent Irish history. Are we all thought to be living in a 1944 bubble, preserved by nightly amazement at Bing Crosby as Father Chuck O’Malley in Going My Way?

How can Irish Catholic parents ever forget that it was other parents – never their bishops – who alerted them to the deadly danger of believing that seminaries and ordination would make men incapable of harming children?

It is from whistleblowers against institutional abuse and other men and women of integrity that we Catholic laypeople best learn the meaning of the common Christian priesthood of all of the faithful – people such as Marie Collins, Mary Raftery, Peter McVerry, Gordon Wilson, Michael McGoldrick, Martin Ridge, Catherine Corless, Maurice McCabe, Tom Doyle, Veronica Guerin, Ian Elliott, the founding CEO of the National Board for Safeguarding Children in the Catholic Church, and Sister Consilio of Cuan Mhuire.

That understanding, guided by the Holy Spirit, will in time reshape the ordained Catholic ministry and renew the Irish Church, when all Irish bishops have fully accepted what is plainly visible to all.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!