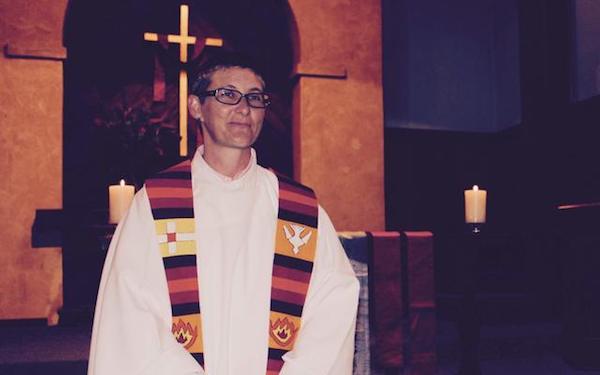

Winona Catholic church, led by a woman, celebrates 10th anniversary

Ten years ago, a Winona woman decided God’s calling was more important than being in good standing with her church.

She made a bold move. An illegal move as far as the Catholic Church as an institution was concerned.

She became a Catholic priest.

Kathy Redig, a hospital chaplain of 20 years at Winona Health, was ordained in 2008 by the Roman Catholic Women Priests.

She then established, with the help of her supporters, the All Are One Roman Catholic Church, which offers Mass on Sundays in the Lutheran Campus Center in the same building as Mugby Junction on Huff Street. Today it celebrated its 10-year anniversary as a church with a reception that’s open to the public from 11:30 a.m. to 2 p.m. after Mass.

“It’s really humbling when I think of the good things that have happened in these 10 years,” Redig said. “It’s just a blessing.”

Redig is a valid priest, meaning she was ordained by a bishop who falls within the apostolic succession in the Roman Catholic Church — a church hierarchy that passes down priesthood after a candidate has gone through an extensive process.

But Redig’s existence as a priest is illegal, because the church’s law, Canon Law 1024, states only men can become priests — the Vatican last month again reemphasized that law.

“A lot of people thought we were going rogue,” Redig said. “But if one really truly believes and respects that we are all created equally then we should have the opportunity to serve.”

The Daily News reached out to Bishop John M. Quinn and the Diocese of Winona-Rochester multiple times in a variety of ways for comment but was unsuccessful.

Redig is a valid priest, meaning she was ordained by a bishop who falls within the apostolic succession in the Roman Catholic Church — a church hierarchy that passes down priesthood after a candidate has gone through an extensive process.

But Redig’s existence as a priest is illegal, because the church’s law, Canon Law 1024, states only men can become priests — the Vatican last month again reemphasized that law.

“A lot of people thought we were going rogue,” Redig said. “But if one really truly believes and respects that we are all created equally then we should have the opportunity to serve.”

The Daily News reached out to Bishop John M. Quinn and the Diocese of Winona-Rochester multiple times in a variety of ways for comment but was unsuccessful.

‘No one up there that looked like me’

A lifelong Catholic, Redig about 25 years ago began to feel a disconnect with some aspects of the Roman Catholic Church.

“As a woman I would look at the altar and there was no one up there that looked like me,” she said.

She would ask questions about it. The answers were always the same.

“The statement that always came down was that Jesus didn’t choose any women — which isn’t true — and that women do not image Jesus,” she explained. “Jesus did choose women. A woman was the first one to announce the resurrection.”

She also felt a disconnect with the male centered language used in church services. So again she asked.

“Well God is male — the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit,” the priests would tell her. “So the language for God is going to be that.”

Now that Redig has studied more, she said that also isn’t true.

Excommunicated but ordained

Redig began the process to be ordained through the Roman Catholic Women Priests — a group started by seven women in 2002 who were ordained by three valid and legal Bishops who were willing to put their reputation on the line to stand behind the women and their efforts.

Two weeks before being ordained, Redig went to speak to the then current bishop — Bishop Bernard J. Harrington — to ask if he would like to ordain her.

He said no.

Then he handed her a letter that would pull Redig’s certification to be a hospital chaplain.

And there was one more thing.

“He said, you know you’ll be excommunicated (from the Catholic Church),” Redig recalled.

She continued to step forward along the journey she felt pulled to and in May of 2008 she was ordained in Kryzsko Commons at Winona State University by Bishop Patricia Fresen.

The support surrounding her was immense, she said. Some of that support was public. And other support was behind private doors.

Shannon Hanzel, a parishioner at All Are One and a friend of Redig, said some people were scared to attend or support the church once it was established, because of possible repercussions. Some worried they would lose a job that was connected to the Catholic Church or catholic schools. Others were scared of being excommunicated.

“Fear was stopping people,” Redig said.

But it didn’t stop everyone.

“In the Old Testament, the spirit, Sophia, is spoken of,” Redig said. “The scriptures speak of God in feminine terms, but the men of church choose not to speak of that.”

After years of questions and getting no satisfying answers, the moment came when she felt pulled to become a priest.

On a beautiful sunny Saturday morning, Redig was washing clothes and reflecting about church, the disconnection, and her love for God.

She turned to her husband and said, “I think the only way we’ll find a church that connects with us if we do it ourselves,” she recalled.

Her husband stopped what he was doing. He looked into her eyes. He agreed with her. They made the decision together that’s what they would do.

“After I made the decision there was a great deal of peace,” she said. “And peace is a sign of the Spirit.”

‘All are welcome in this place’

On a recent Sunday, the All Are One Roman Catholic Church was filled with about 20 parishioners who sang, recited and worshiped with Redig.

Dressed in a white robe, a white cord around her waist, and a single hair clip holding her hair from her face, Redig led the group in song. Drowning out the music in the coffee shop next door, a single phrase of their song rang throughout the room.

“All are welcome in this place,” they sang in harmony.

Among those singing, was Dick Dahl — a Catholic priest who attends the church and fills in Redig’s spot when she’s gone.

“She really exemplifies what being a priest is and what being a Christian is,” Dahl said. “I have such a respect for her and what she’s doing and what she stands for. I think of Martin Luther King when he marched in defiance of unjust laws and was put in jail.”

Hanzel agrees.

“Kathy is extremely pastoral,” Hanzel said. “Her story is really one of courage.”

The congregation gives 75 percent of the money collected — totaling about $3,500 a quarter — to charities and initiatives in the city, country and world including Doctors Without Borders, the Women’s Resource Center of Winona, Islamic Center of Winona and more. Also, each week the congregation collects food for the food shelf.

“This is a tremendously generous congregation and we try to use that to give back to the people who need it,” Hanzel said.

Parishioner Lou Guillou said Redig is inspirational is so many ways.

“She is a valuable priest,” he said.

Guillou added that, in some ways, he appreciates what women priests bring to the table more than their counterparts.

“In distributing communion, they always take it last, rather than taking it first and then giving everyone else,” Guillou said. “They serve everyone else and take last. It’s just a simple thing of bringing in the feminine aspect.”

Redig is a good person, Guillou said with conviction.

In talking about Redig, Hanzel said she hopes one day that women are openly accepted as priests by the Catholic Church.

“I don’t think I’ll see women be treated equally in my life, but I hope during my daughter’s life it will be a reality,” she said.

But in the meantime, Redig will continue to be a valid, yet illegal, Catholic priest.

“I am very much following the model of Jesus,” Redig said. “I’m following the call I’ve heard.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!