— Women’s ordination, priestly marriage, LGBTQ Catholics

By Claire Giangravé

What many will take away about the Synod on Synodality, the monthlong summit on the future of the Catholic Church, is that the 450 clergy and lay faithful called to the meeting skirted the key agenda items of women’s ordination, marriage for priests and acceptance of LGBTQ Catholics.

On Saturday, after the synod released a tepid summary of its work, the Women’s Ordination Conference pronounced itself “dismayed” by the failure of the synod to allow women to become priests.

“A ‘listening church’ that fails to be transformed by the fundamental exclusion of women and LGBTQ+ people,” a statement read, “fails to model the gospel itself.”

The term LGBTQ did not make it into the final document at all, earning the “disappointment” of New Ways Ministries, a network of gay Catholics and their allies, in its statement on Sunday, though it noted that the group drew encouragement from some of Pope Francis’ words of support.

But for the synod’s organizers, the event was never about providing definitive answers on these topics but about promoting dialogue and overcoming division. “Many ask for results. But synodality is a listening exercise: prolonged, respectful and humble,” Cardinal Mario Grech, secretary-general of the synod, said Saturday evening.

In the final 42-page document, titled Synthesis Document for a Synodal Church in Mission and approved by 364 voting participants in the meeting, the summit is portrayed as a success, with most of the 20 separate points passing by overwhelming majorities, even if no single paragraph obtained full consensus.

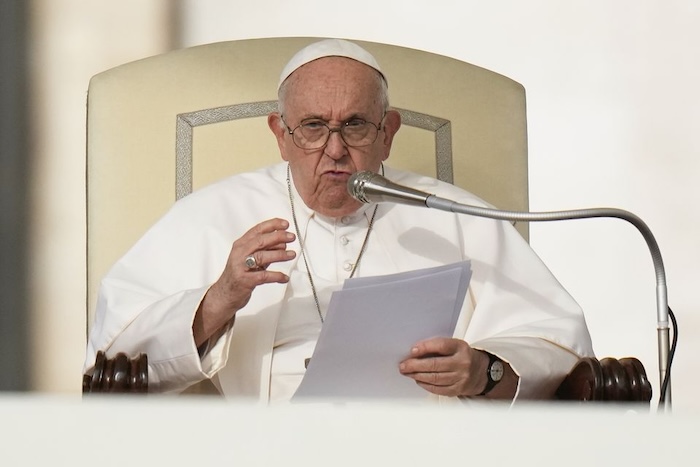

During the event, which opened Oct. 4 with a Mass presided over by Pope Francis, participants talked about the spirit of friendship, respect and dialogue overcoming polarization even in the most divisive debates. Even conservative clergy who were initially critical, including German Cardinal Gerhard Müller and the Austrian Cardinal Christoph Schönborn agreed the synod was a positive experience.

Divisions were, nonetheless, evident: In votes on the individual points in the final document, 69 attendees voted against a paragraph on the possibility of women becoming deacons, who are ordained to preach at Mass but not to celebrate the Eucharist or hear confessions. Mentions of considering the possibility of married priests drew 55 negative votes, or 15% of the voting membership.

Attendants wrote that they are aware that the term synodality awakens “confusion and concern” among many that the teaching of the church will be changed. Since its start, the synod has been accompanied by vocal criticism of conservative prelates who believe the summit is a Trojan horse aimed at forwarding progressive agendas in the church.

Some of those conservatives had bridled at the portrayal of this year’s synod as a completion of the work of Vatican II, the meeting called by Pope John XXIII in the early 1960s seeking to reconcile the church with the demands of changing society. Since then, many progressives have felt that those reforms have been muted or ignored and looked to the synod to make good, increasing conservatives’ fears regarding the dilution of tradition and the power of the hierarchy.

The document’s opening section indeed presents the Synod on Synodality as a “further reception” of Vatican II, but while it recognized the almost familial conflicts posed by the small discussion groups — “We also share that it’s not easy listening to different ideas, without immediately giving into the temptation of answering back,” the document read — participants said that through prayer the effectiveness and primacy of synodality in the church eventually came through.

“A substantial agreement emerged that, with the necessary clarifications, the synodal prospective represents the future of the church,” the document read. The document, drafted with the assistance of theologians, describes synodality as “a journeying of Christians toward Christ and the Kingdom, together with all of humanity.”

In his speech to the synod assembly Wednesday (Oct. 25), Francis further laid out a view of a Catholic Church centered around the “infallibility of faithful people.” The faithful, the pope explained, share an intuition of the beliefs of the church that needs to be interpreted and adopted by the church as a whole.

The closing document proposes that updates to canon law be made to enlarge the participation of people in the church.

Adding to the document’s vision of a more open power structure is its call for the church to be more receptive to individual cultures around the Catholic world, and it urges the church to combat xenophobia and racism.

The document also emphasizes the need to promote relationships with other churches and denominations, suggesting that a council of Roman church patriarchs and archbishops be formed to advise the pope on ecumenism, and even proposing a synod on the Eastern churches. Attendees voiced the hope that Easter 2025, when all Christians will celebrate the paschal feast on the same day, may foster further communion among believers.

The spirit of openness infused the synod participants’ recommendations about the hierarchy, calling on bishops to be “examples of synodality.” Among the proposals were the strengthening of lay and clergy councils at the parish and diocesan levels, allowing lay people to have a voice in selecting bishops and reducing the role of the papal nuncio, the Vatican’s ambassador in a given country.

At the top of the power structure, the document said, the council of cardinals that advises the pope, known as the C9, should take on more responsibilities and suggested reforming canon law to offer “dispositions for a more collegial exercise of the papal ministry.”

But there are limits to how democratic the church hierarchy is willing to become. While the presence of lay people at the synod was welcomed in the document, it also warned that “the criteria allowing nonbishops to participate in the synod will have to be clarified.” When the synod rejoins after a year, it stated, “some suggest that there should be a meeting of exclusively bishops to complete the synodal process.”

And synodality seemed to dictate that where the deepest divisions lie, more discussion is needed. On the question of female deacons, which some say would signify a return to early church practice and others call a break with tradition, the document simply acknowledged that women experience inequality in the church but left any decision to already existing commissions created by Francis, promising theological study in time for the next synod assembly.

Participants also asked for further discussion on the issue of celibacy for priests.

In its final section, the document took up the problem of clergy sex abuse, which Catholics around the world, meeting to air their concerns in listening sessions in their dioceses, had asked the synod to address. But apart from recognizing the need to listen to victims of clergy abuse, it did not offer specific proposals on how to prevent abuse or increase clergy accountability.

The document will now be circulated back to those dioceses for consideration by Catholic leaders and congregants. According to German bishops who attended the synod, “It is now up to the local churches, and thus also up to us, to use these spaces which the synod has opened up in order to continue to work on a synodal church, to advance along the synodal paths, and thus to translate the momentum into concrete reflection and action.”

Despite its multitude of proposals and challenges, the first synod closed with more questions than answers. Regarding those Catholics who might be left still “in a situation of solitude” if they obey the church teachings on “questions of marriage and sexual ethics,” the synod’s participants offered “closeness and support.”

“A profound sense of love, mercy and compassion” was shared by participants for those who “feel wounded or cast aside by the church, who desire a place to return ‘home’ where they can feel safe, feel listened to and respected, without fear of feeling judged.”

But the participants declared themselves often caught between the Christian principle of mercy and the need to defend the doctrinal beliefs of the church.

“If we adopt doctrine harshly and with a judging attitude, we betray the gospel,” the document read, “If we practice cheap mercy, we don’t transmit God’s love.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!