A potential flood of lawsuits has spurred the Catholic Church to offer mediation, only if accusers agree not to sue

By Ian Lovett

Four decades ago, Jimmy Pliska says, he was sexually assaulted by his local parish priest on an overnight fishing trip. Now, he has an agonizing decision to make.

Amid a recent wave of sexual-abuse investigations and allegations against the Catholic Church, Mr. Pliska wants to sue the Diocese of Scranton, which employed the priest. But the case is too old to bring to court. Although state lawmakers have proposed lifting the statute of limitations on the sexual abuse of children, it is unclear when—or if—that will happen.

The diocese, meanwhile, has set up a program to financially compensate victims of clergy sexual abuse. In exchange for accepting money from the program, the diocese won’t have to release any documents that might show what church officials knew about the alleged abuse. Mr. Pliska also would be barred from suing the church.

Time is running short for Mr. Pliska, 55 years old, to decide. The church has set a July 31 deadline. “The church shouldn’t be the judge,” he said of the program. “They should be held accountable.”

The Catholic Church has a great deal riding on whether alleged victims take part in compensation programs like the one in Scranton.

Since a widely publicized report last year from the Pennsylvania attorney general, which documented the abuse of more than 1,000 children by Catholic clergy in the state over half a century, public officials around the U.S. have looked for their own ways to pursue allegations made against the church.

More than a dozen states are considering lifting the civil statute of limitations on child sexual abuse or already have done so. The legislation, if passed, would unleash a surge of new lawsuits against the church.

A new wave of sexual abuse litigation would present a serious threat to both the church’s finances and its reputation. Large jury awards and settlements could cost the church millions, while legal discovery could make public documents showing how dioceses dealt with abuse.

As lawmakers debate the measures, Catholic dioceses in at least six states have tried to stem the tide by offering victim compensation programs.

“While no financial compensation can change the past, it is my hope that this program will help survivors in their healing and recovery process,” Joseph C. Bambera, the Scranton bishop, said when the diocese launched its program last fall.

The programs, which are run by third-party administrators outside the church, offer swifter resolution than trials, and alleged victims are less likely to walk away empty-handed. They also shield the church against lawsuits that could cause greater damage.

Payouts pale compared with what victims have won in court. Those who accept settlements must agree not to sue the church in the future.

The programs could ultimately save Catholic institutions hundreds of millions of dollars, said Marci Hamilton, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania who also has worked on clergy abuse cases as a lawyer.

“Settle as many cases as you possibly can, because statute of limitations reform is inevitably going to pass,” she said. “It lets them have the dual action of looking generous but protecting as many assets of the organization as possible.”

Eric Deabill, a spokesman for the Diocese of Scranton, said helping survivors of abuse was the priority. “Across the country, dioceses facing abuse litigation have been forced into bankruptcy,” he said. “This program balances the sincere desire to promote healing for sex abuse survivors while enabling the core mission of the Diocese to continue.”

But for some, the money isn’t enough, raising the prospect that the crisis could drag on for years. Many alleged victims want access to church records about their alleged abusers. Taking a case to court is a chance to make public any evidence that church officials hid the abuse.

When Paul Dunn was offered $200,000 in the Diocese of Brooklyn victim compensation fund, he rejected it. Instead, he plans to sue under New York’s new law. The priest who allegedly abused him is dead, but anyone who knew about it and did nothing should be punished, Mr. Dunn said.

“Once I go to court,” he said, “I’m sure the documents will come out on who was protecting him.”

In a statement, the diocese “denies any cover-up as to Mr. Dunn.”

Open window

After the Catholic Church scandal erupted in Boston in 2002, California became the first state to temporarily lift the statute of limitations, giving adult victims of childhood sexual abuse 12 months to file lawsuits, no matter how long ago the abuse took place.

The church is still paying off loans from the legal settlements that followed.

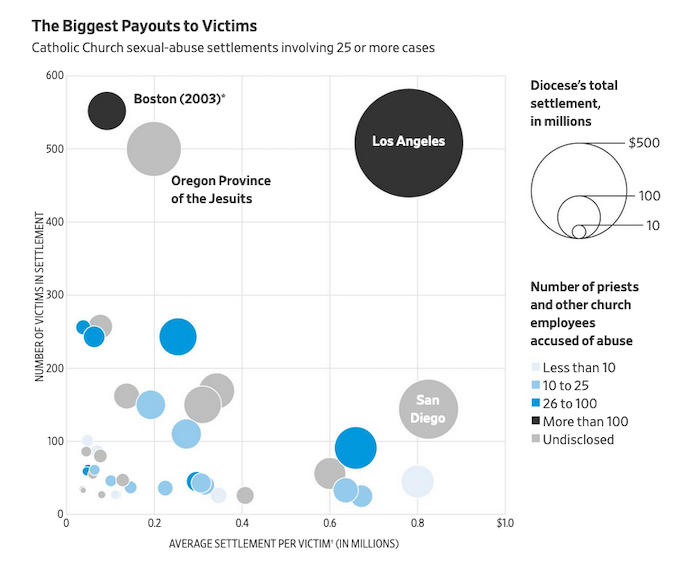

During the one-year window, hundreds of people filed lawsuits against the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, which eventually settled with more than 500 plaintiffs for $660 million.

Faced with more than 140 lawsuits, the Diocese of San Diego filed for bankruptcy in 2007. The plaintiffs eventually received $198 million, less lawyers’ fees and expenses.

In both cases, the diocese covered about half the cost. Insurance and other defendants, including religious orders, paid the rest. Documents showing how church officials covered up abuse in some instances were made public during the proceedings.

Catholic officials around the U.S. have long lobbied against lifting the statute of limitations, arguing that cases from decades ago can’t be fairly adjudicated.

Yet more states are following California’s lead. New York, New Jersey, Arizona, Montana, Vermont and Washington, D.C., passed similar laws this year.

In August, when New York’s one-year window opens to file sex-abuse suits in older cases, hundreds of alleged victims will be unable to sue because they have already accepted settlements from one of five compensation programs in the state.

The Archdiocese of New York in 2016 became the first in the U.S. to open a victim compensation fund. The church hired Kenneth Feinberg and Camille Biros, who ran the September 11 Victim Compensation Fund, to administer the program. Though they are hired and paid by the archdiocese, Ms. Biros said, they operate independently.

Alleged victims tell their stories to the mediators—some in person at offices, and others by phone, over video calls or through their lawyers. No church officials are present. If there is corroboration, such as a police report or another accusation against the priest, the mediators make an offer, Ms. Biros said. Settlement amounts depend on such factors as the victim’s age and the type of abuse, she said, and range from about $500,000 to “considerably lower.”

More than 400 people have submitted claims to the archdiocese, according to Ms. Biros. As of July, in cases already decided, 84% of the victims were offered compensation money. Just over $65 million has been paid to 324 victims, an average of about $200,000 each.

“Our attention and sensitivity as a state and wider community must be to the victim-survivors, not to institutions,” Cardinal Timothy Dolan, the archbishop of New York, said of the compensation programs.

All the dioceses in New Jersey are following the model established in New York, as are seven of the eight in Pennsylvania. Every diocese is Colorado is starting a program. So are six in California, including Los Angeles, the largest archdiocese in the U.S. In each state except Colorado, the legislature is considering or already passed legislation lifting the statute of limitations.

Mitchell Garabedian, a lawyer who has represented hundreds of clients in legal proceedings against the Catholic institutions around the U.S., said participants in the compensation programs are often left with “a feeling of emptiness, a feeling something is missing.” Though they appreciate that past abuse is recognized by the church, he said, many are disappointed to never find out if anyone in the church knew about it and could have stopped it.

One of his clients, Thomas McGarvey, accepted a $500,000 settlement from the Diocese of Rockville Centre, N.Y. He said it was better than going to trial and being cross-examined about the abuse he endured as a teenager.

“At the trial, then you would have had their attorneys grilling me, kind of putting the blame on me,” Mr. McGarvey, 53, said. “It was a hard decision. I would have liked to have sued to express my disgust against the diocese.”

Michael Meenan accepted a settlement of $175,000 from the New York program that he called a lowball offer. He said a priest carried on an inappropriate relationship with him for years in the 1980s, an ordeal he blames, in part, for his financial and psychological problems.

“I never would have taken the settlement had I not been desperately in need of money to survive,” Mr. Meenan, 52, said. “I’m an Ivy League graduate living on food stamps.”

‘I’m very sorry’

Like many alleged victims of sexual abuse, it took Mr. Pliska decades before he discussed it with anyone. “Back then, you didn’t talk about it,” he said.

From afar, it looked like Mr. Pliska was thriving. He finished high school, worked as an auto mechanic in Scranton, got married and bought a house.

Yet the effects of the alleged abuse trailed him during his long silence, he said. After he had two children of his own, he hardly let them out of his sight. They weren’t allowed to sleep over at friends’ houses.

“When they were out in the backyard,” he said, “I was in the backyard overseeing them.”

In 2014, Mr. Pliska said for the first time that Father Michael J. Pulicare, his local parish priest, had raped him. Some members of his family didn’t believe him, and he had no way to corroborate his claim. Father Pulicare died in 1999, and Mr. Pliska didn’t know if the priest had abused anyone else.

Then, a month after the Pennsylvania grand-jury report last year, he read an article in The Wall Street Journal about John Patchcoski, who had grown up just a few blocks away in Scranton.

Mr. Patchcoski also accused Father Pulicare of abusing him on a fishing trip, and Mr. Pliska said the details were similar to his own experience. Both men recall waking up at night with the priest on top of them.

Another childhood friend of Mr. Pliska’s, Mike Heil, read the article and said Father Pulicare also had abused him on a fishing trip.

At least one other accusation has been made against Father Pulicare, according to Diocese of Scranton officials. After the Journal article, Father Pulicare’s name was added to the list of clergy credibly accused of abuse.

As they considered whether to join the victims fund, Mr. Pliska and the others who accused Father Pulicare said the money wasn’t as important as an accounting of who in the church knew about what happened to them. They hope the scrutiny would discourage other institutions from hiding abuse.

At least one diocese, in Erie, Pa., offers victims church documents about their alleged abusers. “One of the big concerns for victims was, ‘We want to see the files,’” Lawrence T. Persico, the Bishop of Erie, said. “It’s very important to be able to do what we can for these victim-survivors.”

Scranton, like most other dioceses offering compensation programs, won’t open its files on accused clergy. “We chose not to engage in time consuming and contentious legal discovery,” said Mr. Deabill, the diocese spokesman.

“They’re just trying to lower their costs” in case the law changes, Mr. Patchcoski said. “They’re taking advantage of us.”

The money is hard to turn down, though. The three men said they would likely file a claim and see what the diocese offered, then decide.

Mr. Pliska, who is recently divorced and living with his parents, struggles to make child-support payments. He could use the money, he said, but would rather go to court, where the proceedings would be public.

In May, Mr. Pliska visited the Scranton cathedral. By chance, he saw the bishop outside and told him about the alleged abuse and its effects on his life, his marriage, his children and his faith in the church.

“It’s been 40 years of hell,” Mr. Pliska said. “It felt as if I could deal with it, but I couldn’t. It’s like a cancer.”

“I’m very sorry,” Bishop Bambera said. “Please know, if it’s any help, that the compensation fund is available.”

“What we would much rather see is it go to the courts,” Mr. Pliska said.

“I understand,” Bishop Bambera said. “A dollar amount never makes anything up. But there is a need for us to be able to say to you, ‘This is something that we can give you.’ ”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!