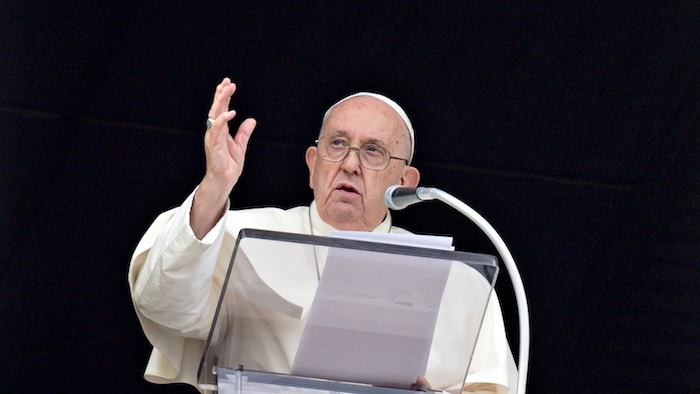

— Pope Francis has established himself as one of the most boundary-pushing popes the church has ever had. Here are his stances on same-sex marriage, trans people, LGBTQ+ parents, and more.

By

Every few months, many LGBTQ+ folks find themselves asking the same question: what is even the deal with the pope?

Since becoming the 266th leader of the Catholic Church in 2013, Pope Francis — née Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio — has established himself as one of the most boundary-pushing popes in modern history. That led a group of five cardinals to issue a list of concerns, or dubia, in October 2023 challenging some of his most radical positions on LGBTQ+ rights and other issues.

Still, in the Catholic church, “radical” is subjective. Francis has certainly taken many positions that soften Catholic doctrine when it comes to LGBTQ+ people and issues. That isn’t a hard thing to do, given that his predecessor Pope Benedict believes gay marriage will bring about the apocalypse and some leading bishops even lobbied against an LGBTQ+ suicide hotline. But Francis has also contradicted himself and split some very specific hairs regarding LGBTQ+ rights. And on a few issues, like the concept of transgender people, his principles are strictly orthodox.

With so many different statements released over the past decade, it can be hard to figure out what Pope Francis actually believes, especially about queer and trans people and how we live our lives and fit into the Church. Below, we’ve rounded up the highlights from Francis’ papacy so far to make sense of how Catholicism might slowly be changing, and in what ways it’s still the same old $30 billion tax haven we’re used to.

What is Pope Francis’s stance on gay people?

What is Pope Francis’s stance on gay people?

Francis has generally taken the open-ended position that God loves gays and wants them welcomed in the church. In 2013, the Pope famously said that “if someone is gay and is searching for the Lord […] who am I to judge?” The statement was widely lauded at the time simply for being the first time a pope had ever said the word “gay,” rather than “homosexual,” in public remarks. (Since then, Francis has frequently spoken of “homosexuals” in various comments.) In 2015, Francis affirmed the ministry of Bishop Jacques Gaillot, who was removed from his ministry in 1995 after he blessed gay couples. In 2018 Francis said that gay Catholics are made and loved by God, and in a surprise meeting at the Vatican in 2020, told families of LGBTQ+ youth that “God loves your children as they are.”

But while he has regularly affirmed queer love in the abstract, the pope has been less positive about what all those homosexuals might end up doing with one another. While “being homosexual is not a “crime,” as Francis exhorted in January 2023, he went on to say that “it’s a sin […] first let’s distinguish between a sin and a crime.” This seemed to contradict another statement Francis made in 2019, when he said the “tendencies” to be gay “are not a sin.”

In particular, Francis has said that queer relations between clergy members are a “serious concern” and “worry” him. “The question of homosexuality is a very serious one,” Francis said in a 2018 book interview, and there was “no room” for anyone in the ministry to enter a queer relationship (though heterosexual ones were still okay).

“In our societies, it even seems homosexuality is fashionable. And this mentality, in some way, also influences the life of the Church,” he fretted, recommending “persons with this rooted tendency not be accepted into ministry or consecrated life.”

Does Pope Francis support same-sex marriage?

Well, yes, but actually no. Francis is a vocal supporter of legal “civil unions,” but that’s as far from Church orthodoxy as he is willing to stray. This position dates back to his pre-papal days as Cardinal Bergoglio, when he was a leading proponent for a 2010 same-sex “civil union” bill in Argentina. As soon as that bill fell through, however, Bergoglio wrote a letter to the Carmelite Nuns of Buenos Aires to sound the alarm about another bill legalizing same-sex “marriage,” which was ultimately successful. The law would represent “the outright rejection of the law of God,” the pope-to-be wrote at the time, by “a ‘movement’ of the father of lies,” — i.e., Satan — “that seeks to confuse and deceive the children of God.”

After Kim Davis infamously refused to grant same-sex marriage licenses to gay couples as a Kentucky county clerk in 2015, claiming she acted “under God’s authority,” Pope Francis met with Davis that September during his visit to Washington, D.C. A Vatican statement asserted Francis only interacted with Davis as part of an audience with “several dozen persons,” and that their meeting “should not be considered a form of support of her position.” But Davis and her lawyers at the conservative Liberty Counsel have told a different story, saying Francis said he would pray for Davis, “thanked her for her courage and told her to ‘stay strong.’”

The pope has continued to ride this line for years, calling same-sex marriage “a contradiction” in some 2019 comments that LGBTQ+ figures roundly condemned. Francis doubled down in 2021, saying that since “marriage” is a God-delivered sacrament, the Church did not have the power to alter its definition. Civil unions can “help the situation” in a legal sense, he explained, but “marriage is marriage.”

As of now, Pope Francis still holds that “civil unions” are the only way to reconcile the religious and legal definitions of marriage. In his response to five conservative cardinals’ complaints in 2023, Francis expressed support for clergy (like Gaillot) who bless same-sex unions, but only if those blessings “do not convey a mistaken concept of marriage.” That privilege is still reserved for “a man and a woman” — specifically, the ones who are “naturally open to procreation.” Super.

What does Pope Francis think about transgender people?

Unsurprisingly, what the pope says about trans people doesn’t always match up with how he treats them. Francis is most infamously known among trans communities for comparing trans people to nuclear weaponry, comments that gave us the best flagging shirts of all time. “[G]ender theory […] does not recognize the order of creation,” Francis said in a 2014 interview, and thus “man commits a new sin, that against God the Creator” whose design “is written in nature.” Francis reiterated that concept in 2016, writing that trans youth “need to be helped to accept their own body as it was created” rather than physically transition.

In 2019, the Vatican distributed a memo entitled “Male and Female He Created Them,” a document which declared both trans and intersex identities “only a ‘provocative’ display against so-called ‘traditional frameworks’” that “seek to annihilate the concept of ‘nature.’” If you’re nonbinary, no you’re not: that idea is “nothing more than a confused concept of freedom in the realm of feelings and wants,” wrote Cardinal Giuseppe Versaldi in the memo, published by the Vatican Press. In early 2023, Francis went even further: “gender ideology, today, is one of the most dangerous ideological colonizations” in the world, he said, because “it blurs differences and the value of men and women.” Later in the year, he did make an allowance that trans people could receive baptism, but only if doing so would not cause a “scandal.”

But despite apparently seeing them as unnatural threats to divine creation, Francis has at least provided some amount of material support to trans people in need, particularly since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2020, Francis donated an undisclosed amount of money to a group of unhoused trans sex workers sheltering in an Italian church. Since then, he has gone on to meet with the same group at least five separate times, eating pasta with them and over 1,000 others at a lunch in November recognizing the Church’s World Day of the Poor.

For those trans people, the Pope is a major force for good, at least more so than he’s been viewed elsewhere in the world. “We transgenders in Italy feel a bit more human because the fact that Pope Francis brings us closer to the Church is a beautiful thing,” Carla Segovia told Reuters after the lunch. “Because we need some love.”

Does Pope Francis support LGBTQ+ parents and adoption rights?

On this, the Pope has taken a much clearer stance: not on your life. If a “marriage” is no longer between a man and a woman, then-Cardinal Bergoglio wrote in his 2010 letter to the Carmelite Nuns, adopted children will be irrevocably harmed from growing up with gay parents. “At stake are the lives of so many children who will be discriminated against in advance,” he lamented, “depriving them of the human maturation that God wanted to be given with a father and a mother.” (It should be noted that children raised by LGBTQ+ parents develop the same way their peers do, and may even have some advantages.)

Since becoming pope, Francis has not officially changed his stance. In 2013, a bishop reported that the pope was “shocked” by a civil union bill in Malta that would have allowed LGBTQ+ couples to adopt. The year after, Francis reiterated that children have “a right to grow up in a family with a father and a mother” and warned against being tempted towards “the poisonous environment of the temporary.” As comparatively boundary-pushing as some of his other views might be, we wouldn’t expect Francis to change on this one anytime soon.

Does the Pope at least like my pets?

Bad news! Owning pets is also a metaphysical threat to the fabric of reality, even for straights. “Many, many couples do not have children because they do not want to, or they have just one — but they have two dogs, two cats,” Francis said in 2022, calling the trend a “denial of fatherhood or motherhood” that “diminishes us” and “takes away our humanity.” We can only imagine what the guy thinks of Sapphics who own more than one litterbox.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Nun reveals she secretly blessed same-sex couple 15 years ago

— ‘I would do it again’

Sister Anna Koop doesn’t regret blessing a same-sex couple 15 years ago.

A Catholic nun has revealed that she secretly blessed a same-sex couple 15 years ago – long before the Pope Francis indicated that same-sex couples could receive blessings – and she’d do it again.

Roman Catholic Sister Anna Koop blessed the couple, one of whom was a personal friend, 15 years ago because they were in love and “Jesus did not say love was confined.”

The 85-year-old told CBS News that she was aware she might face consequences from the Church, but went ahead with with the private blessing anyway. In her own words, she “blessed the love they celebrate”.

In early October, LGBTQ+ groups praised Pope Francis for saying that same-sex couples could have their unions blessed.

Sister Koop, who became a nun in the late 1960s and has spent her career mainly in Denver, focussing on homelessness and poverty, said the Pope’s support of same-sex couple blessings made her feel that her blessing 15 years ago has been supported.

She said she never experienced consequences over the secret blessing and still keeps in touch with the couple. They are still together and have two children.

Sister Koop doesn’t regret her actions.

“I did it once and I would do it again,” she said.

In the Church of England, however, blessing services for same-sex couples may be a considerable way off.

The Bishop of London, Dame Sarah Mullally, has said it’s unlikely that such services will take place before 2025.

The delay comes amid what Mullally called a “time of uncertainty” for the Church due to division over the General Synod – the Church of England’s decision-making body – announcing in February it would continue to prevent priests ordaining same-sex marriages, but blessings would be offered instead.

In a move towards increased inclusivity, in January the Church of England formally apologised for its historically “hostile” treatment of LGBTQ+ people.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

It shouldn’t seem so surprising when the pope says being gay ‘isn’t a crime’

— A Catholic theologian explains

Once again, Pope Francis has called on Catholics to welcome and accept LGBTQ people.

“Being homosexual isn’t a crime,” the pope said in an interview with The Associated Press on Jan. 24, 2023, adding, “let’s distinguish between a sin and a crime.” He also called for the relaxation of laws around the world that target LGBTQ people.

Francis’ long history of making similar comments in support of LGBTQ people’s dignity, despite the church’s rejection of homosexuality, has provoked plenty of criticism from some Catholics. But I am a public theologian, and part of what interests me about this debate is that Francis’ inclusiveness is not actually radical. His remarks generally correspond to what the church teaches and calls on Catholics to do.

‘Who am I to judge?’

During the first year of Francis’ papacy, when asked about LGBTQ people, he famously replied, “If someone is gay and he searches for the Lord and has good will, who am I to judge?” – setting the tone for what has become a pattern of inclusiveness.

He has given public support more than once to James Martin, a Jesuit priest whose efforts to build bridges between LGBTQ people and the Catholic Church have been a lightning rod for criticism. In remarks captured for a 2020 documentary, Francis expressed support for the legal protections that civil unions can provide for LGBTQ people.

And now come the newest remarks. In his recent interview, the pope said the church should oppose laws that criminalize homosexuality. “We are all children of God, and God loves us as we are and for the strength that each of us fights for our dignity,” he said, though he differentiated between “crimes” and actions that go against church teachings.

Compassion, not doctrinal change

The pope’s support for LGBTQ people’s civil rights does not change Catholic doctrine about marriage or sexuality. The church still teaches – and will certainly go on teaching – that any sexual relationship outside a marriage is wrong, and that marriage is between a man and a woman. It would be a mistake to conclude that Francis is suggesting any change in doctrine.

Rather, the pattern of his comments has been a way to express what the Catholic Church says about human dignity in response to rapidly changing attitudes toward the LGBTQ community across the past two decades. Francis is calling on Catholics to take note that they should be concerned about justice for all people.

The Catholic Church has condemned discrimination against LGBTQ people for many years, even while it describes homosexual acts as “intrinsically disordered” in its catechism. Nevertheless, some bishops around the world support laws that criminalize homosexuality – which Francis acknowledged, saying they “have to have a process of conversion.”

The “law of love embraces the entire human family and knows no limits,” the Vatican office concerned with social issues said in a 2005 compilation of the church’s social thought.

In 2006, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops recognized that LGBTQ people “have been, and often continue to be, objects of scorn, hatred, and even violence.” And expressing care for other human persons – “especially those who are poor or in any way afflicted” by the indifference or oppression of others – represents obligations for all Catholics to embrace.

As the Francis papacy now nears the end of its 10th year, it is becoming more and more common to hear Catholic leaders attempting to make LGBTQ people feel included in the church. Chicago’s Cardinal Blase Cupich has called on pastors to “redouble our efforts to be creative and resilient in finding ways to welcome and encourage all LGBTQ people.” New York’s Cardinal Timothy Dolan has welcomed LGBTQ groups in the St. Patrick’s Day parade, against the wishes of many New York Catholics.

In this most recent interview, Francis emphasized that being LGBTQ is “a human condition,” calling Catholics to see other people less through the eyes of doctrine and more through the eyes of mercy.

A new ‘political reality’

The rapid change that has happened in prevailing social attitudes about the LGBTQ community in recent decades has been difficult to process for a church that has never reacted quickly. This is especially because the questions those developments raise touch on a gray area where moral teaching intersects with social realities outside the church.

For decades, church leaders have been working to reconcile the church with the modern world, and Francis is stepping in places where other Catholic bishops have already trodden.

In 2018, for example, German bishops reacting to the legalization of gay marriage acknowledged that acceptance of LGBTQ relationships is a new “political reality.”

There are signs that parts of the church are moving even more quickly. Catholics in Germany, in particular, have called for changes to church teaching, including permission for priests to bless same-sex couples and the ordination of married men.

The next chapter

But those actions are outliers. Francis has criticized the German calls for reform as “elitist” and ideological. When it comes to the civil rights of LGBTQ people, the pope is not changing church teaching, but describing it.

I believe the challenge the Vatican faces is to imagine the space that the church can occupy in this new reality, as it has had to do in the face of numerous social and political changes across centuries. But the imperative, as Francis suggests, is to serve justice and to seek justice for all people with mercy above all.

Catholics – including bishops, and even the pope – can think, and are thinking, imaginatively about that challenge.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Pope Francis writes to controversial nun, thanking her for 50 years of LGBTQ ministry

Pope Francis has sent an encouraging letter to an American nun thanking her for her 50 years of ministry to LGBTQ Catholics, more than two decades after she was investigated and censured by the Vatican for her work.

In his letter dated Dec. 10, Francis wrote that Sister Jeannine Gramick has not been afraid of “closeness” and without condemning anyone had the “tenderness” of a sister and a mother. “Thank you, Sister Jeannine, for all your closeness, compassion and tenderness,” he wrote.

He also noted her “suffering … without condemning anyone.”

Gramick, who lives just outside of Washington, D.C., in Mount Rainier, Md., said that the letter felt like it was “from a friend.”

“Of course, I was overjoyed,” she said. “It felt like a turning point in the church, because for so long, this ministry has been maligned and in the shadows.”< For decades, Gramick and her New Ways Ministry co-founder, the late Rev. Robert Nugent, were considered controversial by some church leaders for the workshops they did about the science and theology around LGBTQ topics. Gramick said she would not provide her opinion, but she would present the Catholic Church’s teaching, as well as doctrinal positions from more moderate and liberal theologians. Gramick said she was under scrutiny from the Vatican for about 20 years before officials issued a declaration that she would be barred from ministry. “The ambiguities and errors of the approach of Father Nugent and Sister Gramick have caused confusion among the Catholic people and have harmed the community of the Church,” the 1999 statement from the Vatican’s Congregation for the Doctrine of Faith said.

Gramick later transferred to another religious order to keep doing her work.

A spokesman for the Vatican did not respond immediately Friday to a message seeking to confirm the authenticity of the pope’s letter to Gramick. The letter, first published on Friday in the Catholic publication America magazine, is the latest in a series of several letters the pontiff has written this year to gay Catholics and others who are serving and advocating for LGBTQ people.

The pope’s letter follows actions by the Vatican on gay rights that have frustrated Francis’s more liberal supporters. Early in his papacy, he famously declared: “If a person is gay and seeks God and has good will, who am I to judge?” But he has upheld church doctrine that calls LGBTQ acts “disordered.” Last year, the Vatican’s doctrinal body said that Catholic priests cannot bless same-sex unions.

In December, a Vatican official apologized to New Ways Ministry for having pulled a reference to it on the Vatican website, drawing praise from the group as a rare and “historic” apology and for restoring the reference. New Ways revealed that Pope Francis had written them two letters earlier in 2021 praising their ministry. In those letters, Francis noted Gramick’s work, that he knew “how much she has suffered,” describing her as “a valiant woman who makes her decisions in prayer.”

The Rev. James Martin, a New York City-based priest known for his ministry affirming LGBTQ Catholics, said he has received a few letters from Pope Francis but made one of them public in July 2021. Gramick’s letter, he said, is significant because she has been censured by the Vatican.

“For most LGBTQ Catholics, Sister Jeannine is a real hero, so they’ll be delighted. They’ll rightly see this as one of Pope Francis’s steps forward,” Martin said. “He doesn’t change church teaching on this but take steps … added up, all the steps, we’ve come a long way.”

Gramick said official investigations came after the late Cardinal James Hickey, the former archbishop of Washington, wrote to the Vatican asking officials to pressure Gramick and Nugent to stop their ministry. An investigation was launched in 1988 and in 1999, the Vatican issued its censure.

“It was devastating,” she said. “What can I say? It didn’t feel good.”

A spokeswoman for the archdiocese of Washington did not immediately return a request for comment on the letter.

Gramick said she and others from New Ways Ministries met with Cardinal Wilton Gregory, the archbishop of Washington, in October and told them about the letters Pope Francis had sent the ministry. “Sounds like you’re pen pals,” Gregory told them, according to Gramick.

Gramick said she started her ministry when she was 29 while studying in graduate school and befriended a gay man who had left the Catholic Church for the Episcopal Church. In his apartment, she organized Mass for gay and lesbian people who had left the Catholic Church.

“When the liturgy was over, they had tears in their eyes because they felt they were being welcomed home again,” she said.

Gramick said she hopes the church will eventually change its position on sexual ethics and listen to the growing number of parishioners who have become more LGBTQ affirming.

“What would I say to LGBT Catholics is, ‘Hold on, it will change,’ ” she said. “We have to make our views known so that the officials of the church can properly express that change.’ ”

Francis also wrote to America magazine national correspondent Michael O’Loughlin, who is a gay Catholic, commending him for reporting on Catholic responses to the HIV/AIDS crisis.

From the earliest days of his papacy, O’Loughlin said, the pope has reached out to individuals in a personal way by calling people on the phone and writing the string of LGBTQ-related letters.

“There’s a lot of hurt and pain in the LGBT community and a single letter or group of letters is not going to fix that,” O’Loughlin said. “He’s interested in highlighting Catholics living out their faith even in areas that have been historically difficult for the church.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

How gay rights went mainstream — and what it cost

Activists wanted revolution. They got rainbow Nikes.

By

Pride Month has gone mainstream. Taylor Swift released a new LGBTQ anthem, and companies from Macy’s to Doc Martens have turned pride into a marketing tool.

This widespread acceptance is a far cry from the gay liberation movement that once championed an alternative lifestyle and a culture all its own. Merging into the mainstream wasn’t always a central goal for the movement, particularly after the Stonewall riots, a pivotal moment in gay history that took place 50 years ago this month.

How did a culture and identity once defined by its marginalization — the criminalization of same-sex relationships, the classification of homosexuality as a mental illness — turn into a fashion statement?

Ironically, the religious right, the news media and the AIDS crisis helped this happen. As journalists spotlighted the movement and its victories throughout the 1970s, conservative Christians feared the “homosexual agenda” was gaining traction. But when HIV/AIDS, an illness that initially appeared to strike only gay men, became a news story, evangelical leaders claimed it was God’s punishment for immorality. Reporters repeated this frame, and subsequent stories explored whether bathhouses and non-monogamous relationships had fueled the epidemic.

By the mid-1980s, the gay liberation movement had pivoted, embracing mainstream institutions and fighting for the same rights as heterosexuals. Their victories spurred many Americans to reevaluate their ideas about gender roles and same-sex relationships. But greater acceptance of the LGBTQ community came at the expense of Stonewall’s animating vision: the freedom to be and to live how one wanted.

That freedom made headlines in the decade after Stonewall. Journalists profiled a community with its own music, mores and fashion, as well as an uninhibited sex scene. They depicted a burgeoning culture, one that called into question conventional norms such as monogamy and marriage. Reporters also covered the victories of gay rights activists, who persuaded the American Psychiatric Association to remove homosexuality from its diagnostic manual and voters to support local anti-discrimination ordinances.

But even as mainstream acceptance grew, a backlash was brewing. In 1977, entertainer Anita Bryant mobilized the Save Our Children Campaign, encouraging church folks in Dade County, Fla., to support the repeal of a Miami ordinance that prohibited discrimination based on sexual orientation. To the surprise of many, Bryant succeeded.

The Rev. Jerry Falwell, a popular television and radio preacher, was among her backers. In 1979, encouraged by Beltway Republicans, Falwell launched Moral Majority, a grass-roots political organization for religious conservatives. This new voting bloc supported traditional family structures — nuclear families with a male breadwinner and a stay-at-home mother — and denounced feminists, abortion rights supporters and people in the LGBTQ community.

Their first goal was to elect Ronald Reagan to the presidency, and after he won, Falwell attributed Reagan’s 1980 victory to Moral Majority support.

Falwell’s rise would be pivotal for the LGBTQ community because of another story in the news: Physicians had identified a mysterious virus that seemed to target gay men. Initially, news outlets reported sporadically on the virus, assuming most readers weren’t interested. But by early 1983, AIDS coverage exploded.

Physicians still did not know how it spread, but there was growing agreement that blood was a carrier and speculation that casual contact could cause infection. AIDS was no longer a “gay plague,” as the media initially called it. Using words that stoked alarm among the “general population” — the catchall term news outlets used for heterosexual Americans — journalists reported that AIDS was incurable and often fatal.

The medical news moved the subject onto the front pages, as journalists began reporting on the disease’s human toll. One New York Times article described the disease’s “emotional anguish.” The Rev. William Sloane Coffin, a well-known liberal minister, said he counseled “AIDS victims” who “felt that this was in some way God’s punishment.” He assured them that “being gay was not a sin.”

Coverage such as this highlighted the moral dimension of the epidemic, and religious conservatives saw an opportunity.

During a Fourth of July “I Love America” rally, Falwell declared that AIDS was “God’s way of ‘spanking’ us,” adding that even if most Americans were “innocent” of sodomy, heterosexuals who countenanced homosexuality were rebelling against God.

Falwell quickly became a go-to guy for HIV/AIDS stories. For reporters looking to balance stories about the moral dimension of AIDS, Falwell offered everything they could want. Waving a Bible and citing scripture, he seemed the embodiment of religious orthodoxy to secular journalists who knew little about Christianity. He also had colorful quotes, an army of Christian soldiers and the ear of the president. Best of all, he was always ready to talk.

Before long, the televangelist’s message influenced how reporters framed HIV/AIDS. One Newsweek story around that time explored how the virus ended “a decade of carefree sexual adventure.” The article’s subheads included “Punishment,” “Hostility” and “Backlash” — all Falwellian themes — and the text repeatedly quoted the minister. The piece also noted that after 743 deaths and 1,922 “victims,” some gay rights activists were questioning the movement’s valorization of sexual freedom.

Most gay leaders quoted in the article mentioned a “new sobriety.” The language of the piece and its sources presumed that monogamy was preferable to “excess,” “sobriety” and “flamboyance,” and middle-class values to “hedonism.” The story also suggested that commitments to work and family could bridge the differences between “us” and “them.” Good gay people, like straight people, accepted monogamy and capitalism, it said, while bad gay people lived bohemian lifestyles, indulged in casual sex and died. AIDS coverage policed the possible: a win for conservatives, because it shifted the midpoint of American political life rightward.

By stigmatizing the alternative gay culture and promoting normative institutions and practices, this coverage unwittingly helped shift the focus of the gay liberation movement to civil rights — an area in which they had more hope for success. Many stopped challenging mainstream ideas and institutions — from marriage and religion to gender and bodily autonomy — and started fighting for the same privileges as heterosexuals, including the right to marry, serve in the military, adopt children and be free from discrimination in housing, employment and public accommodation. Their successes have frustrated religious conservatives who are still contesting the “homosexual agendaTarget. But it came at a cost. Protesters at Stonewall fought for the freedom to be who they were and to live how they wanted. They wanted a revolution; they got rainbow Nikes.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!