Pastor, retired bishop marry same-sex couple at Charlotte’s First United Methodist Church

Officiating at the wedding could result in reprimand or a church trial if complaints are filed

The denomination’s Book of Discipline only sanctions marriage between a man and a woman

By Tim Funk

They knew it could mean a reprimand or even a church trial that might end their careers.

Still, the pastor of Charlotte’s First United Methodist Church and a retired bishop who once did jail time with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. decided to go ahead over the weekend and preside at the wedding of John Romano and Jim Wilborne.

The two Charlotte men became the first same-sex couple in North Carolina to get married – at least publicly – in a United Methodist church.

But the mainline denomination’s Book of Discipline sanctions only marriage between a man and a woman. So there could be consequences for the Rev. Val Rosenquist and Bishop Melvin Talbert – the clergy who performed the wedding – if any complaints are filed with Bishop Larry Goodpaster, who leads the Western North Carolina Conference of the United Methodist Church.

Rosenquist, senior pastor since last July at First United Methodist, the uptown Charlotte church where Saturday’s marriage took place, said on Sunday that the Book of Discipline has “institutionalized oppression and discrimination.”

Last August, she said, the leadership board at First United Methodist voted that any member of the church could get married in the sanctuary, even if that defied the Book of Discipline.

“These folks are our brothers and sisters,” Rosenquist, 59, said about LGBT members. “It’s just a matter of obeying our covenant with one another throughout the church, that we are to minister to all and to treat all the same. I’m just following what I was ordained to do, what I was baptized to do.”

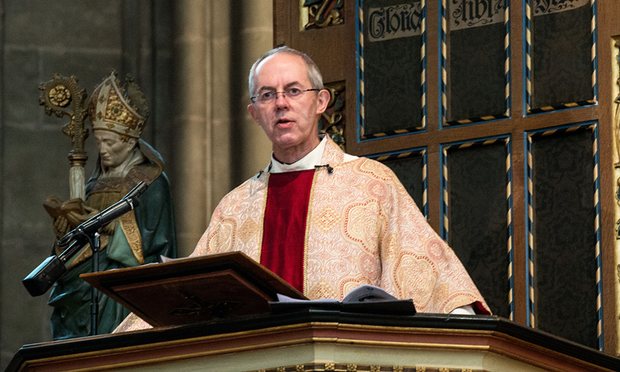

The 81-year-old Talbert, a retired United Methodist bishop based in Nashville and a one-time leader of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, spent three days and three nights in a jail cell with King in 1960. He called his disobedience of Methodist rules against same-sex marriage an act of “biblical obedience.”

“Discrimination is discrimination, no matter where it is, and it’s wrong,” Talbert said. “I hope that what we did here yesterday will be an act of evangelism for people … who are looking for safe places to come because they don’t want to be identified with anti-gay (sentiment).”

On Sunday, Talbert delivered the sermon at First United Methodist Church, telling about 150 people in the pews that, like African-Americans, women and other past victims of discrimination, LGBT persons are being ridiculed and ostracized “simply because of the way God created them.”

He also pointed out what the congregation already knew: “Your pastor could have complaints filed against her, and I could, too. … But it’s the right thing to do. If it costs us, if there are consequences, so let it be.”

Reached Sunday by the Observer, Michael Rich, communications manager for the Western North Carolina Conference of the United Methodist Church, released a brief statement on behalf of Goodpaster.

“We are aware of the wedding at First United Methodist Church on Saturday,” it read. “Bishop Goodpaster will follow the procedures in The Book of Discipline if a formal complaint is filed.”

Goodpaster is scheduled to retire in September.

A U.S. Supreme Court ruling last year legalized same-sex marriage in all 50 states. Mainline Protestant denominations such as the Episcopal Church, the Presbyterian Church U.S.A. and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America have given their clergy the green light to perform gay weddings in their sanctuaries.

But the United Methodist Church, the country’s largest mainline denomination with about 7 million U.S. members, remains officially opposed to “same-gender marriage,” as do some other denominations – including the Southern Baptist Convention and the Roman Catholic Church.

Just weeks after North Carolina’s ban on same-sex marriage was thrown out by a lower federal court in 2014, Goodpaster sent a letter to clergy in his conference reminding them that the United Methodist Church’s rules had not changed.

Ministers can attend same-sex weddings, Goodpaster said in his letter. But, he added, any who preside at a same-sex marriage ceremony or sign the marriage certificate could face possible reprimand or even a church trial.

Goodpaster told the clergy then that he could not permit “actions counter to the Book of Discipline,” the denomination’s rule book.

Rosenquist and Talbert said they both alerted Goodpaster before the Saturday wedding that they planned to go ahead with it, whatever the consequences.

First United Methodist Church has long been among Charlotte’s gay-friendly churches. It was the first Charlotte church, in 2014, to join the Reconciling Ministries Network, a national coalition of United Methodist groups that advocate for LGBT persons and others “pushed to the margins,” in the words of the uptown Charlotte church’s then-pastor, the Rev. Jonathan Coppedge-Henley.

The Book of Discipline could be changed at the denomination’s next General Conference, set for May in Portland, Ore. But the global denomination is divided on same-sex marriage, with opposition from churches in Africa as well as from conservatives in the United States. There has even been talk in recent years about the denomination splitting over the issue.

In 2012, at the General Conference in Tampa, Talbert stood up to say that the church needed to practice biblical obedience by striking language in the Book of Discipline that he said “criminalizes clergy for ministering to gays and lesbians.”

Since then, he has been taking that message around the country, urging progressives to stand up and tell conservatives that “it’s our book, too. We can read it and interpret it.” In 2013, Talbert married a same-sex couple in Alabama. A complaint was filed and, a year later, there was a settlement without a trial.

The most famous case of a Methodist minister defying the same-sex marriage ban came in 2007, when the Rev. Frank Schaefer, then of Pennsylvania, officiated at the wedding of his gay son. A church court later defrocked him, though he was subsequently reinstated.

Romano and Wilborne, the Charlotte couple married at First United Methodist on Saturday, said they wanted to be married in the church where both have been active – Wilborne for 20 years.

“It was just so amazing to us to be married in our own church,” said Romano, 52, a furniture sales representative, “and not do it under the radar, but do it in a way to promote change.”

Wilborne, 52, who has been with Romano for more than five years, said the couple felt it was important to stay in their United Methodist Church. “We didn’t leave it to go where it was easier (to get married),” he said. “We stayed here because we love this church. … It’s our home. We just feel blessed. We’re at the right place at the right time to have this opportunity.”

They said the Saturday wedding was attended by more than 250 people – including about 30 supportive United Methodist clergy. Also in attendance: Charlotte Mayor Jennifer Roberts, who is a friend of the couple’s.

Not everyone was pleased. On Sunday, after Talbert’s sermon at the 11 a.m. service, a former member of the church stood up at his pew to object to the same-sex wedding and to Talbert’s justification for it. His words competed with an announcement that the collection would be taken up, so few in the church heard him.

Former teacher Charles Walkup later told the Observer he said that “as one who’s personally dealt with homosexuality, I affirm that the Methodist (Book of) Discipline is correct.”

Walkup, who ended his membership in the church after it joined the Reconciling Ministries Network, added that he tried to speak up because “Jesus warned of false shepherds who mislead his precious sheep.”

But the church members who attended Sunday seemed happy about the marriage and what they called the courage of their pastor.

“Val is doing what the church needs – going out on a limb without complete support from the church hierarchy. But it is the right thing to do: We’re all God’s children,” said Patricia Ingraham, a retired banquet manager who has been a church member since 2006. “Some of my dearest friends are gay. Why should they be treated differently than I’m treated?”

Complete Article HERE!

After Modern Family, over glasses of soda and water (this is a Christian crowd, after all), the group watches a video produced for a college project by one of the students about life on campus. There are several scenes of Wheaton kids walking around the school. It was shot so their faces could not be seen.

After Modern Family, over glasses of soda and water (this is a Christian crowd, after all), the group watches a video produced for a college project by one of the students about life on campus. There are several scenes of Wheaton kids walking around the school. It was shot so their faces could not be seen.