By Mike Rivage-Seul

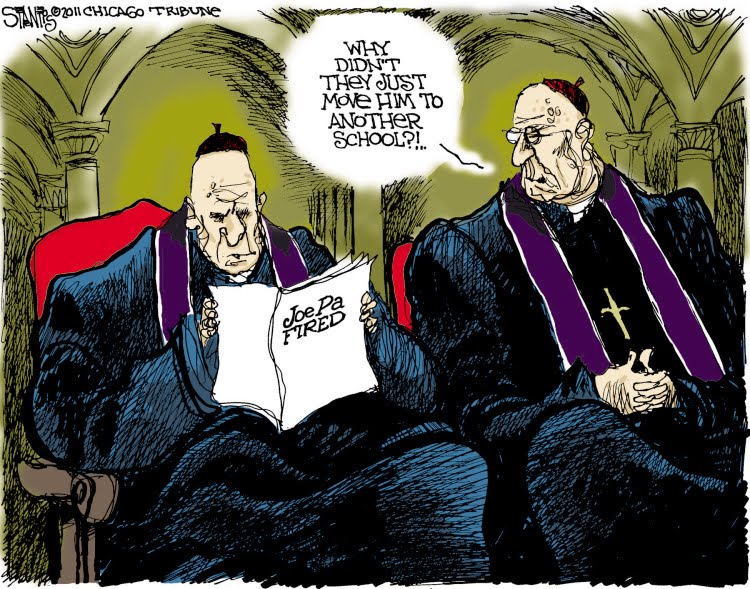

Many were pleasantly surprised by the severity of the sanctions the National Collegiate Athletic Association placed on Penn State following its investigation of the Jerry Sandusky child abuse scandal. The NCAA’s measures evidenced an appropriately serious approach to unspeakable crimes. At the same time, however, the athletic association’s aggressive sanctions contrasted sharply with the lack of appropriate response to much greater crimes on the part of Roman Catholic clergy. It made some wonder what it might look like if the Catholic Church handled its infinitely larger scandal in a fashion similar to that of the NCAA.

Of course, the Penn State’s board of trustees had initially tried to defuse its shameful situation by having the institution’s president resign and by firing Joe Paterno, the football program’s legendary coach. Eventually, they even removed “Joepa’s” statue that (dis)graced the entrance way to the football stadium in Happy Valley.

Of course, the Penn State’s board of trustees had initially tried to defuse its shameful situation by having the institution’s president resign and by firing Joe Paterno, the football program’s legendary coach. Eventually, they even removed “Joepa’s” statue that (dis)graced the entrance way to the football stadium in Happy Valley.

But the NCAA went far beyond that — even further than most had expected. It appointed high profile Independent Counsel, Louis Freeh, to investigate responsibility for Sandusky’s crimes and the cover-up that followed. Then in the wake of Freeh’s damning final report, it fined the University $60 million dollars — the amount the football program takes in annually. It ordered the program to vacate its winnings since 1998 (thus depriving Paterno of his legacy as the winningest coach in NCAA football history). It forbade the program to extend any football scholarships for the next four years, and released all of its current players from their ties to Penn State, making them immediately eligible to play elsewhere. The football program will be devastated for years to come.

The NCAA’s bold sanctions couldn’t be further from the response of the Roman Catholic hierarchy to its child abuse scandal. There instead the “old boy” defense of the institution and the members of its all male club kicked in just as it did at first inside Penn State’s football program when the Sandusky crimes initially came to light. At Penn State, the wagons were circled, Sandusky was mildly chided while everyone in charge from the University president and Joe Paterno on down denied any knowledge or responsibility. The attitude that “boys will be boys” threatened to carry the day.

The equivalent of that attitude and (non)response still prevails within the Holy City despite the shameful involvement of priests in raping and otherwise sexually abusing children on a worldwide scale that absolutely dwarfs anything that happened in Happy Valley. In the face of thorough investigations by independent groups (e.g. the absolutely devastating indictment published last year in Ireland) the Cardinal of New York invoked the “bad apples” defense, and protested that “only” a small portion of the clergy was tainted.

But what would it have looked like if (impossibly!) the Catholic Church had responded like the NCAA?

If it had done so:

- Pope Ratzinger would have resigned immediately.

- All cardinals and bishops who had covered up the scandal would have been removed from office.

- The canonization process for John Paul II would have been terminated, because of the way he down-played the sex scandal. This would be the equivalent of removing Joepa’s statue.

- An investigation independent of the Vatican would have been launched headed by an unimpeachable figure — say the Dali Lama, perhaps joined by Sr. Pat Farrell, President of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious (LCWR) which is currently being investigated by the Vatican.

- Upon completion of its investigation (assuming it would have reached conclusions similar to the one in Ireland), the commission would have:

- Fined the Catholic Church $500 billion — the equivalent of one year of the R.C. church income. The money would be used world-wide to aid victims of sex abuse and to institute programs to educate clergy about human sexuality using the best insights of current sociology and psychology.

- Removed from the list of genuine popes all those whose public crimes made them unworthy of the title “Vicars of Christ.” Here the Borgia popes come to mind, as well as Pope Pius XII for his silence about the Jewish Holocaust. (Obviously, the process of his canonization would be abruptly ended.) This would be the rough equivalent of Penn State’s vacating its football wins since 1998.

- The exclusion of women from the priesthood would be reversed, and seminary scholarships would be extended world-wide to women desiring to receive Holy Orders.

- Mandatory celibacy would of course be set aside as a requirement of the priesthood — and a major contributor to the issue at hand.

- A reforming Church Council (Vatican III?) would be ordered to deal with the sex abuse and related problems — to be attended only by bishops not involved in the abuse scandal and subsequent cover-up. Their places would be taken by women elected by national bodies equivalent to the LCWR in the United States.

Of course, nothing like the results just described is remotely possible. Roman Catholic insulation from the external processes necessary to achieve such outcomes prevents that eventuality. The only external source capable of moving the church in the desired direction belongs to the Catholic faithful itself. It alone has the authority to withhold church attendance and contributions till the desired decisions of reform are taken.

But not to worry: such pressure from the faithful will eventually be applied willy-nilly. That is, the faithful will either wage a purposeful campaign of withholding attendance and financial support in the light of failed church leadership.

Or alternatively (and more likely) the once-faithful will be driven away from the church as the realization dawns that a college sports organization possesses sounder moral character than what pretends to be the “Mystical Body of Christ.”

Complete Article HERE!