By Jean Hopfensperger

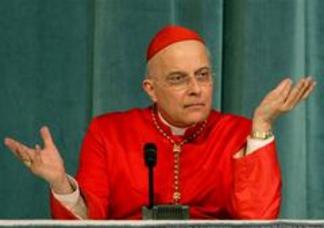

The Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis has hired a prominent criminal defense attorney to continue its investigation into possible sexual misconduct by Archbishop John Nienstedt.

Attorney Peter Wold has been retained to continue the investigation completed by the Greene Espel law firm in July, Auxiliary Bishop Lee Piché confirmed Monday.

Attorney Peter Wold has been retained to continue the investigation completed by the Greene Espel law firm in July, Auxiliary Bishop Lee Piché confirmed Monday.

Wold has met with at least one man — previously unidentified in the media — who filed affidavits in the misconduct investigation earlier this year.

Joel Cycenas, a former archdiocese priest and former friend of Nienstedt’s, acknowledged he met with Wold last week. He had some concerns.

“I met with him [Wold] and they are trying to discredit my own affidavit,” wrote Cycenas in an e-mail. “I don’t get it.”

Cycenas would not provide details about the content of his affidavit or answer further questions.

Interviewed last summer, Nienstedt denied any sexual impropriety with Cycenas.

Wold was retained “to help with some remaining details” in the Nienstedt investigation, said Piché in a written statement. The results of the initial investigation were not made public. Details of the current investigation also were not forthcoming.

“It would be a disservice to those involved to discuss any more of the specifics of the investigation while it is ongoing,” said Piché.

About 10 men have come forward with allegations of sexual misconduct by Nienstedt while they were seminarians or priests, said Jennifer Haselberger, an archdiocese whistleblower who was interviewed by Greene Espel.

She said the archbishop also was accused of retaliating against those who refused his advances or otherwise questioned his conduct. The allegations appear to stem as far back as the 1980s and 1990s, when Nienstedt was working in the Archdiocese of Detroit.

Cycenas, a 47-year-old from the Forest Lake area, was among those interviewed by Greene Espel. Ordained in 2000, he became a parish priest at Holy Spirit Church in St. Paul several years later.

Nienstedt acknowledged last summer that the two were once good friends, and that they met while he was bishop of the New Ulm Diocese.

“We were very good friends at one point,” said Nienstedt. “We met at World Youth Day in Toronto [in 2002]. …

“We went to the State Fair together,” said Nienstedt. “Oftentimes I would stay at his rectory at Holy Spirit when I was coming up [from the New Ulm Diocese] to fly out the next morning.”

The friendship dissolved after Cycenas left the priesthood in 2009, Nienstedt said.

The friendship dissolved after Cycenas left the priesthood in 2009, Nienstedt said.

Cycenas now works as an outreach manager for a major Twin Cities nonprofit.

Haselberger said she was surprised the archdiocese has hired another lawyer to investigate the allegations.

“My impression was they [Greene Espel] were very consciously and diligently making efforts to get to the truth of the matter under very difficult circumstances,” she said.

“Why would they investigate again?” Haselberger asked. “I hope it won’t be an attempt to slander the victims, which would be a poor reward for coming forth.”

Haselberger also was concerned about the financial implications for the archdiocese, which is laying off staff and floating the possibility of bankruptcy. “Maybe their insurance is paying for it, who knows?” she said. “I’d like to know, ‘What are they hoping to accomplish?’ ”

Piché did not respond to written questions about the exact nature of Wold’s work, including the difference between Wold’s investigation and the previous one. However, he did note that none of the allegations against Nienstedt involved children or criminal activity with an adult.

Complete Article HERE!