By Marisa Iati

In a yellow townhouse just steps from Georgetown University on a recent evening, members of the campus group Catholic Women at Georgetown talked about how the Virgin Mary strengthens them in hard times as they shared a dinner of Domino’s pizza.

In between swapping thoughts on homesickness and avoiding sin, the conversation turned to new allegations of sexual abuse by clergy in a church under siege.

The group’s president, Erica Lizza, asked the dozen students seated in a circle how they lean on Mary as the faith they’ve relied on for spiritual sustenance faces a crisis.

“I still do feel a level of disgust and betrayal by the Catholic hierarchy,” Lizza, a 21-year-old senior, said after the weekly dinner discussion. “As someone who cares a lot about her faith and who is very involved in a campus ministry organization, it’s something that there’s no escaping from.”

Similar conversations are playing out in dining halls and campus ministry centers across the country as college students wrestle with what it means to be Catholic at a time when they feel disappointed and angered by the church.

The church has seen multiple scandals in recent months: former U.S. cardinal Theodore McCarrick’s resignation amid accusations of abuse and a sweeping grand jury report out of Pennsylvania that implicated more than 300 priests in abusing about 1,000 children.

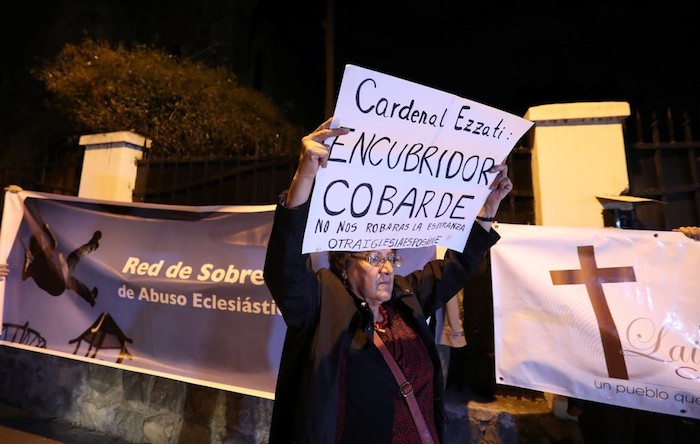

Then, Pope Francis accepted Cardinal Donald Wuerl’s resignation from his position as Washington’s archbishop after the Pennsylvania report described Wuerl as having a mixed record on responding to sexual abuse in his former diocese of Pittsburgh. Wuerl remains in charge of the archdiocesan administration until the pope names his successor. Clergy sex abuse scandals have also rocked Chile and Australia.

In an era when the church is frequently perceived as behind the times on matters of importance to them, some young Catholics have responded to the latest setbacks by pulling further away from the beleaguered institution, while others have drawn closer.

This generation of Catholic college students has grown up amid the stain of the sexual abuse crisis, which was first exposed by The Boston Globe in 2002 and has since implicated clergy around the world. Most can’t even remember a pre-scandal church.

At the same time, they and young people generally are a critical demographic for the future of Catholicism, which has an aging parishioner base and has struggled to attract and retain young people.

Catholicism has seen the largest decline in participation among major religious groups, according to a report in 2016 from the Public Religion Research Institute. Almost one-third of Americans said they were raised Catholic, but just 21 percent currently identify that way.

At a gathering this month of several hundred bishops to discuss the church’s ministry to young people, Pope Francis acknowledged those who have stood by the church, despite its failings.

“I thank them for having wagered that it is worth the effort to feel part of the Church or to enter into dialogue with her; worth the effort to have the Church as a mother, as a teacher, as a home, as a family, and, despite human weaknesses and difficulties, capable of radiating and conveying Christ’s timeless message,” Pope Francis said to open the synod, according to a copy of his remarks released by the Vatican.

Increasing disaffiliation with religion

Disillusionment over clergy sex abuse is not the only force pulling younger generations away from the Catholicism, particularly in the United States.

Increasingly over the past few decades, young adults have realized they can choose their own faith or combination of faiths, apart from those of their parents — or affiliate with none at all, said Theresa O’Keefe, a theology professor at Boston College who specializes in young adult faith. A growing distrust of institutional leadership of all kinds also means some students respond rather jadedly as more allegations of clergy abuse come to light, O’Keefe said.

William Dinges, a professor of religion and culture at Catholic University, said people who feel distant from the church are more likely to be affected by the abuse crisis than those who are devout. Many young adults are already frustrated with what they view as Catholicism’s less inclusive stances on topics such as same-sex marriage and gender equality, Dinges said.

“The young person has to have a good answer: ‘Why am I here?’ ” O’Keefe said. “The church, particularly the leadership, has to come up with a good answer. Why should people show up? Membership is not inevitable, and meaningful membership isn’t inevitable.”

Caroline Zonts, a 19-year-old sophomore at George Washington University, said she had started to feel put off by the Catholic Church long before the abuse crisis reemerged.

Raised “strictly Catholic,” she said the socially liberal political views she developed in high school made her feel less connected to her faith. When she arrived at college, Zonts said she stopped practicing Catholicism, although she still considers herself Catholic.

The recent abuse crisis has become another reason she doesn’t expect ever again to fully immerse herself in the church. It hurts her to think the priests she’s built relationships with may have committed abuse.

“They were mentors for me, they were role models, they were people I went to and talked to about my faith,” Zonts said. “That’s really hard — to know that hundreds of people like that have just abused their positions of power.”

Like Zonts, George Washington University junior Evelyn Arredondo Ramirez felt her more liberal political views were at odds with some parts of her Catholic faith. But even as a supporter of same-sex marriage and abortion rights, the 20-year-old still attended Mass most Sundays during her first two years of college.

Her perspective recently began to shift. Already annoyed with homilies that expressed the priests’ political opinions, her frustration was compounded by the Pennsylvania grand jury report and accusations that Pope Francis had knowingly shielded McCarrick from accountability.

Ramirez doesn’t go to Mass anymore and said she worries about her younger brother’s safety around priests in his home parish.

“I still have my Virgin (Mary) on my desk table, I still have the cross hanging in my room, and I will sometimes just pop into a church and just sit really with God,” Ramirez said. “But I’ve just developed my own idea of what it is to have that connection.”

Questions about the institution, not the faith

Many young Catholics who still consider themselves devout have responded not by turning away but by striving to force change from within the institution. For them, the current crisis is infuriating and heartbreaking, invigorating and empowering, all at the same time.

These young Catholics are among the more than 1,500 Georgetown students who have signed a petition calling on the university to rescind an honorary degree it awarded to McCarrick in 2004 and another it gave to Wuerl in 2014.

A Georgetown spokesman, in a statement, said the university was reviewing the honorary degrees in an effort “to address the deeply troubling revelations about Archbishop McCarrick and those contained in the Pennsylvania grand jury report.”

Among the students who feel unnerved by those revelations is Ana Ruiz, an 18-year-old member of Catholic Women at Georgetown, who said the scandal has made her doubt both her faith and her devotion to the church because the faith itself is closely tied to the institution. Catholics believe the church was founded by Jesus Christ.

“To just kind of see people who definitely do not embody those values that we hold so sacred really makes me question if the institution is working for the good of Christ and the good of the people,” Ruiz said as students cleaned up after the Georgetown discussion dinner.

Although still committed to Catholicism, Ruiz said she could imagine walking away from the institution if she no longer believed it cared about the best interests of lay people. Right now, however, she still feels like God is at the center of the church’s ministry.

“In that sense, I feel like I could never really break away,” Ruiz said. “But everything else that surrounds it, the humanly aspect of the Church, there could be potential for me to be like, ‘No, I can’t deal with that anymore.’ ”

Lizza’s childhood was steeped in Catholicism, with Sunday school and family Mass attendance and her mother reading to her from a children’s Bible. Even so, she was unsure how much she wanted to engage with her religion when she got to Georgetown because she was concerned about how her devout faith would mesh with that of her peers. Then a friend convinced her to join the Catholic women’s group and Lizza found a home.

Three years later, shocked and disgusted by the magnitude of the clergy sex abuse problem, Lizza said she started thinking maybe all bishops should resign. She fought to reconcile the idea of clergy who claim to stand for selfless love and a pursuit of justice with the knowledge that many had failed to live up to that promise.

Lizza said she never considered leaving the church. Rather, she felt stronger in her conviction that good people needed to stay involved in the institution to correct its course.

She still wants more lay people involved in the Church, despite how hard it was for her to attend Mass after the McCarrick allegations and the Pennsylvania report. She also wants people to be less skeptical of abuse victims.

“Covering it up sure as heck doesn’t work,” she said. “And the only way to really address it is to look at it square in the face and make some hard choices.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!