Cardinal Law celebrated mass in April 2005 inside St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City.

By Tovia Smith

When the cardinal’s residence was built in the 1920s atop a hill in the leafy, most western outpost of Boston, it was modeled after an Italian palazzo. The grand mansion, replete with ornate mahogany and marble appointments, has stood as a testament to the Boston Archdioceses’ stature in the very Catholic city of Boston. Political candidates — local and national — would come calling, and even the Pope came to visit.

When Cardinal Bernard Law took up residence in the Renaissance Revival mansion, Boston’s Roman Catholic movers and shakers would flock to the backyard for his garden party fundraisers.

Today, it’s a steady stream of students hauling backpacks, and members of the public traipsing across that same property. The mansion, now owned by Boston College, has been gutted and converted to an art museum and meeting rooms — a remarkable fall from grace that parallels that of the Boston Archdiocese itself.

A total of 65 acres of prime church property – possibly its most valuable in Massachusetts — was sold in a fire sale, after the clergy sexual abuse crisis, when the church was struggling to pay some $85 million dollars in settlements to victims. In the years since, the cost of settling claims surpassed $200 million, and the church’s declining fortunes have been more than just financial.

Cardinal Law’s death this week reawakened a flood of emotion and anger over the decades of sexual abuse that finally came to light in 2002, and at the archbishop’s role in allowing predator priests to move to new parishes, where they would prey on more unsuspecting victims. The revelations that began in Boston eventually engulfed the church worldwide, and the reverberations continue to be felt, nowhere more so than in the once all-powerful Boston Archdiocese.

“The church’s influence took a big hit in 2002, that’s undeniable,” says Domenico Bettinelli, who used to be director of new media for the Archdiocese, and now works as an anti-abortion rights activist. “There’s no doubt that since the great scandal broke … our public voice has been muted in many ways because our moral authority has rightly been questioned.”

It’s a far cry from the old days, when the church was almighty, and the cardinal was closer to king, according to Thomas P. O’Neill III, former Massachusetts state legislator and lieutenant governor. He’s also son of the former speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, Tip O’Neill.

“When my dad served in the state legislature and Cardinal [Richard James] Cushing said [to do] something, I can assure you, a Catholic majority in the state legislature paid attention to it, and did it,” says O’Neill.

Powerful ambitions

Cardinal Law long hoped he could also command that kind of obedience, after he arrived in Boston in 1984. With his booming baritone, and penchant for the regal trappings of the office, he did engender a deference and reverence that was in no small part derived from his influence with the Vatican. As one of the most senior American prelates, he was as well-connected as he was well-regarded outside Boston. He had the ear of Pope John Paul II, and was talked about as the man who might become the first American Pope. He was in regular conversation with President George H. W. Bush, and was a player on the world stage, instrumental in arranging the Pope’s first visit to Cuba; He was described in a 1990 newspaper article as “the first Archbishop of Boston to have a foreign policy.”

Boston’s Cardinal Bernard Law conducts his first Mass after being appointed a Cardinal, at Our Lady of Victories Church in Boston.

A 1990 Boston Globe story, headlined “The Cardinal’s Ambitions,” outlines a typical week in Law’s life;

“He had mulled over Third World debt with Mexican bankers in Washington, D.C., brainstormed anti-abortion strategy with U.S. bishops in New York City, and jolted a visiting Northern Ireland official with a pointed question about conditions in Catholic schools there. The following Sunday he would leave for Cuba and his second tete-a-tete with Fidel Castro.”

But at home, the Catholic Church’s influence was on a slow decline that had begun under Law’s immediate predecessor, Cardinal Humberto Sousa Medeiros, who largely refrained from politics. By the time Law came to town, shifting demographics and changing social mores had significantly changed the landscape, further diminishing the church’s authority. And much as he wanted to reclaim the clout wielded by Cardinal Cushing, Cardinal Law never quite could.

“Law wanted to play that role and recreate that world, in a sense, but that world was already gone,” says James O’Toole, a history professor at Boston College, and former archivist for the Archdiocese of Boston. “There was a kind of polish to him as someone who knew what position he was in, and he was going to run with that, but he wasn’t able to do it.”

“By the time I got [into politics], you weighed everything that was being said by the church hierarchy, and you did it respectfully,” says O’Neill. “But did you follow blindly? No. Those days were all gone by the time I got there. [Lawmakers] paid attention to [Cardinal Law] … but they did not always comply.”

The election of 1986, O’Toole says, already revealed how the cardinal’s rigid Roman orthodoxy, and rightward leaning wasn’t flying with his Massachusetts flock. Cardinal Law lobbied for two referendum questions: one to ban state funding for abortion, and the other to permit some state support of parochial schools.

“Cardinal Law campaigned very strongly on both of those issues and he lost both of them decisively,” O’Toole says.

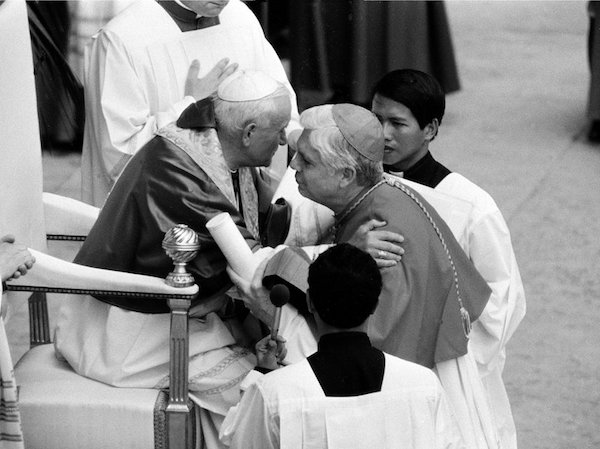

Cardinal Bernard Law embraced and kissed by Pope John Paul II as he is officially installed as cardinal by the Pontiff during a solemn Consistory in St. Peter’s Square in 1985.

By the time another decade passed, the gap had so swollen between Boston’s Catholic Church and Boston Catholics on social issues, leaving Cardinal Law venting that both Massachusetts senators and the governor were wrong on the abortion issue.

“Only I am right,” he said.

A few years later, the church would also falter in its efforts to block gay marriage, as lawmakers were paying more heed to the voice of their constituents, than the cardinal’s’s.

“There used to be an assumption that [the archdiocese] was speaking for the majority of people in the church,” says State Rep. Byron Rushing. “But the average Roman Catholic state representative or state senator knew that there were many Roman Catholics in their district that are in favor of it. They weren’t all on the same page … [like] in the old days.”

Still, the institutional power of the Catholic Church in heavily Catholic Boston, would continue to earn Law a ranking by Boston Magazine as one of the three most powerful figures in Boston, even through the late 90s.

Protecting its own

Indeed, former Attorney General Martha Coakley says that sway was what enabled the Archdiocese to keep the lid on the clergy abuse and on what higher-ups were doing that allowed the abuse to continue.

“The church as an institution was incredibly powerful in Boston, in protecting its records and using its authority to cover up what was in retrospect, an awful conspiracy to hide [the abuse] and protect the church’s reputation,” she says.

Furious backlash

But when the 2002 sexual abuse crisis threw the church into turmoil, and prompted a furious backlash, it was all over. With the church under siege, the balance of power shifted abruptly.

Law became the “poster boy” for the church’s cover up. The cardinal’s mansion was surrounded every day by swarms of protesters calling for his resignation. From his mightiest perch, he was reduced to being grilled by victims’ lawyers, under oath, about what he knew and when he knew it. One attorney recalls that when pressed during a deposition, Law turned to his attorney, protesting and asking if he really had to answer. The answer came back that yes, he did.

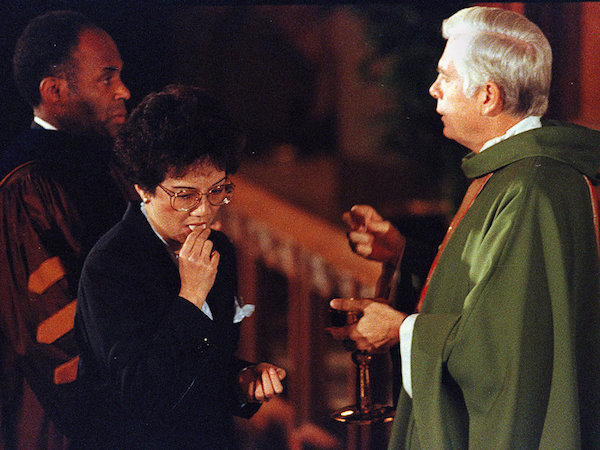

Philippine President Corazon Aquino receives Holy Communion from Cardinal Law during Mass at St. Ignatius Church in Newton, Mass. in 1986.

“The church lost all its influence,” Rushing says. On Beacon Hill, the church’s longtime lobbyist, who’d been a fixture at the statehouse, didn’t even dare show up.

“I would joke with him,” Rushing recalls. “You know like, ‘You can always come into my office, because I know you don’t want to go anywhere else in the building.'”

The cardinal, never shy to testify himself on legislation or use his bully pulpit, was rendered effectively mute. He was side-lined on issues he would have been spearheading, like a Boston Hotel workers strike that involved poor and immigrant workers.

Legislation moved through the State House, including requiring health insurance to cover contraception, and hospitals to offer the morning-after pill. On the other hand, Rushing says the church’s retreat was a big blow to other progressive/liberal efforts he would have liked the church’s help on, like increased assistance to the poor people and immigrants.

“We lost that lobby,” Rushing says. “They just stopped doing it.”

Shortly after the crisis, some Catholic priests in Massachusetts were even flouting the church by speaking out against a ban on gay marriages in Massachusetts, prompting a stern rebuke from above.

At the same time, the church’s financial clout took a nosedive as well. Angry, disillusioned parishioners were leaving in droves, and donations — from collection plates and large institutions— were drying up. After the crisis, the annual Boston Catholic Appeal plummeted to half of what it was.

“Everything went right over the cliff,” said one church official, not authorized to speak on the record. “We were basically in a freefall.”

O’Neill says the Catholic faithful began to distinguish between the mission of the church, and the institution of the church, and found ways to support the former but not the latter. He says that’s still happening, as he saw recently, when fundraising for a local Catholic school.

“In the old days the Catholic Church would support it almost in its entirety,” he says. “Today, you have private folks making contributions directly to [foundations that support that mission] as opposed to through the apparatus of the archdiocese.”

Climbing out out of crisis mode

By all accounts, Cardinal Sean O’Malley, has worked small miracles to restore confidence in the church. Soft-spoken, and low key (he’s way more comfortable in the traditional plain brown habit of his Franciscan order, than the regal garb that Cardinal law favored), O’Malley, has showed genuine compassion for the victims, and a deep commitment to their healing and to church reform. Church officials say attendance has finally stabilized, and donations have climbed back up to pre-crisis levels.

“If you told me before Sean O’Malley had become the cardinal of Boston, that anyone could have come and done the repair that Sean O’Malley has done, I’m not sure I wouldn’t have believed you,” says O’Neill. I think everybody — even Catholics not practicing today — have a very deep seated respect for Cardinal O’Malley.”

Politically, the Archdiocese is slowly recovering some of its voice, but seems to be strategically picking and choosing its fights, to stay more in sync with Boston Catholics. For example, O’Malley has been championing the cause of undocumented immigrants and speaking out on opioid addiction, violence prevention, and education.

“We’re out of crisis mode now, and Cardinal O’Malley is much more engaged politically,” the church official says.

The church recently managed to pull off a legislative win, helping to defeating a measure that would have allowed physician assisted suicide. But Bettinelli cautions even that vote doesn’t necessarily mean an upswing in the church’s influence.

“Lawmakers are voting “based on their faith,” he says. “But I don’t think it’s necessarily because they are being influenced by [O’Malley].”

Catholic participation remains low; just about 20 percent attend weekly mass, compared to 70 percent in the 1970’s, according to the church. Money remains tight, and despite the softer tone coming from both Pope Francis and Cardinal O’Malley, doctrine is not budging on issues like abortion, contraception, or gay marriage, and so the chasm between the church and many of its parishioners on social issues is only widening.

“The rigid school of catholic doctrine … doesn’t sell in the 21st century,” says says Lawrence DiCara who was Boston City Council president in the 1970s.

Close to 70 parishes have been eliminated since 2004, a trend almost surely accelerated by the scandal, but reflective of the broader shift of Catholic America from the old heartland of Boston, N.Y., Chicago and Philly, to the South and Southwest.

Today, as Cardinal O’Malley tries to reboot and boost the Catholic Church, in keeping with his more down-to-earth style, he lives in a modest rectory in the heart of Boston, far from the once majestic mansion that was home to his predecessors.

O’Neill was one of the “movers and shakers” who once reveled at the big parties at Cardinal Law’s residence. “Those were the happy days,” he sighs.

He was also there for the small, private meeting, when a handful of Law’s closest confidantes told His Eminence it was time to quit.

“That was the end of it,” O’Neill says.

Now, he says, “this church is a church in repair, and we have a long way to go.” Then, ever faithful, he adds, “But I think the [new] leadership is destined to do the right thing, and get us to that point.”

As O’Toole puts it, “it’s dangerous for a historian to talk about the future but … the revival will come at some point. You know maybe 100, or 200 years from now … But I don’t think [this decline] will be permanent.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!