The Vatican has at last broken its silence on priests who become fathers, as their children reveal the pain of secrecy

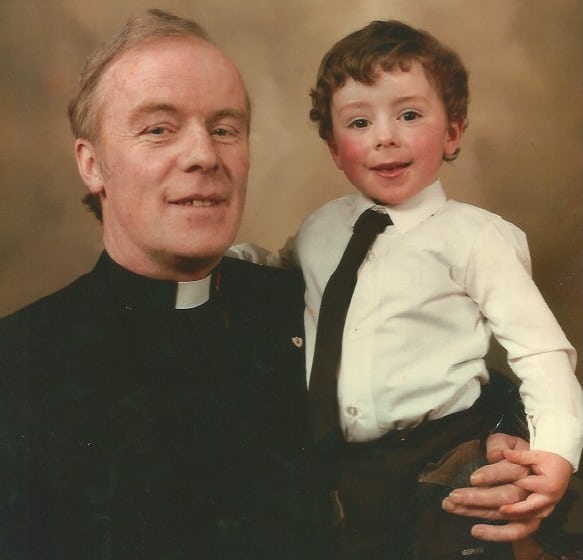

When he was a boy, Vincent Doyle spent most weekends with a priest he believed was his godfather.

Every Friday night they would watch MacGyver and Vincent would stay in a room that the priest, who was called JJ, kept for him. And every morning before school, he would call Vincent to wish him well.

It was not until years later when Doyle, a psychotherapist based in Galway, was sitting in the kitchen with his mother, leafing through old poems the late priest had written, that he asked the question he innately knew the answer to. “I said: ‘He was my father, wasn’t he?’ And I saw a tear come out of her,” Doyle says.

Catholic priests have been breaking their vows of celibacy and fathering children for decades, if not centuries. For just as long, the Vatican has not publicly addressed the question of what, if any, responsibility the church has to provide emotional and financial support to those children and their mothers. Until now.

A commission created by Pope Francis to tackle clerical sexual abuse will develop guidelines on how dioceses should respond to the issue of the children of priests.

The pontifical commission for the protection of minors has been criticised for doing too little on child sexual abuse. Its decision to take up the issue of priest fathers comes after Irish bishops published guidelines this year that have been hailed as a global model.

They say a child’s wellbeing must be the first consideration of a priest father, and that he must “face up” to his personal, legal, moral, and financial responsibilities.

Acknowledgement of the issue has come about in part because people such as Doyle, who has launched an organisation designed to help priests’ children cope with their difficult childhood circumstances, are speaking out like never before.

It is, says John Allen, a veteran Vatican journalist, an example of the “Francis effect”. “He has encouraged a spirit of open discussion. There is a vast global loosening up under Pope Francis, and this is one expression of it,” he says.

In the past, a bishop who was confronted with a priest father would have been most concerned about the priest breaking his vow of celibacy, Allen says. The priest would probably have been urged to avoid being “tempted” by the mother again and told to ensure the child was taken care of, but not have a personal relationship.

Doyle has loving memories of his father, whose surname he adopted. He will not talk about his parents’ relationship out of respect for his mother’s privacy, except to say one thing: they loved each other.

“He did everything he could for me in the circumstances,” Doyle says. “I simply loved him like a son would. The only problem is, you cannot say it.”

When he was a child, he says, his mother was under pressure and lacked visible social support. “People were led to believe that you were the only one.”

While he is encouraged by the signs of progress, Doyle wants the pope to confront the issue personally. When secrecy has been imposed on a child for their whole life, he says, it is a form of abuse that must be addressed.

“The big problem with children of priests is that they technically don’t exist, and until someone says they actually exist, it is a psychological battle that the children face,” Doyle says.

John Anderson, 72, contacted Doyle after hearing about his organisation, Coping International, and was moved to share his story for the first time.

Anderson says he was 18 when he learned that his father was a French priest. He never knew him and his birth certificate still states that his father is unknown. It was not supposed to be that way.

When Anderson’s mother was pregnant, he says, the plan was that she would enter a convent and that he would be adopted by his mother’s doctor.

Instead, his mother kept him and the pair took a £10 ticket to Australia when Anderson was three, armed with a letter of recommendation written by his father, which stated that his mother was a “creditable emigrant”.

As an adult, Anderson underwent years of psychotherapy and experienced bouts of mental illness, an issue he traces back to his difficult childhood with a mother who was incapable of caring for him.

Anderson says he was unable to be a proper father to his three daughters because he was too insecure and incapable of trusting anyone.

“I turned into this ice man in a way,” he says. Anderson went on to be an artist, but it was challenging because he was still unable to access his emotions.

“I had a rotten childhood. I used to pray to God to send me a friend,” he says. After learning who his father was, he wrote a letter to the priest’s order to try to find out more about him. They wrote back, calling him a gold-digger.

“My mother would have gone to her grave with the information, bless her. It’s like lifting the stone, isn’t it? Rolling the rock back from the cave mouth,” Anderson says.

“It has caused so many people so much grief. I’d just like the whole thing in the open. Jesus Christ, he wouldn’t have wanted this.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!