A Roman Catholic cardinal and his top aides lied to their lawyer about shredding a key piece of evidence in the Philadelphia clergy-abuse scandal, the lawyer testified Monday.

Lawyer Tim Coyne was looking for an internal list of 35 suspected predator-priests for a 2004 grand jury investigation. He asked Cardinal Anthony Bevilacqua and four top aides where to find it.

Lawyer Tim Coyne was looking for an internal list of 35 suspected predator-priests for a 2004 grand jury investigation. He asked Cardinal Anthony Bevilacqua and four top aides where to find it.

Coyne said he doesn’t remember any response from Bevilacqua. And the aides — two of whom went on to lead other dioceses — denied they knew where it was, Coyne said.

No one told him that Bevilacqua had ordered the list shredded in 1994, shortly after Monsignor William Lynn, his secretary for clergy, compiled it.

“Everyone who I spoke to said they didn’t know where it was and they didn’t have a copy of it,” Coyne testified Monday.

“Everybody lied to you?” Assistant District Attorney Patrick Blessington asked.

“That’s fair,” Coyne said.

The list is something of a smoking gun in Lynn’s child-endangerment trial, although each side is trying to spin it to their advantage.

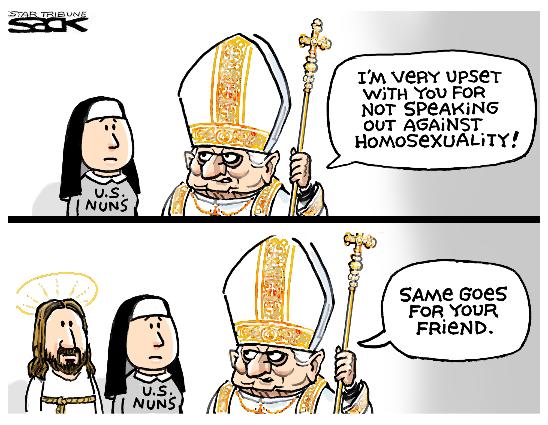

Prosecutors in 2004 were deep into a three-year probe of the archdiocese. Their blistering 2005 grand jury report blasted Bevilacqua, Lynn and others for their handling of abuse complaints lodged against 63 priests, but said no criminal charges could be filed.

It’s not clear if the list — or suggestions that evidence was being shredded — would have helped them make a case against anyone. But one accused priest on the 1994 list continued to lead a South Philadelphia parish until he was suspended this past March.

Lynn, 61, was charged last year over his handling of more recent abuse complaints.

Defense lawyers argue that he alone tried to do something about the festering abuse problem when he served as secretary for clergy from 1992 to 2004. They point to the list as proof.

Lynn told the grand jury that he had decided, after taking office, to go through secret church files to create a list of problem priests who were still on duty. His list described three priests as diagnosed pedophiles, and deemed others “guilty” because they had admitted the abuse. The list was discussed at a February 1994 meeting between Bevilacqua and his closest aides.

According to a memo, Bevilacqua ordered Monsignor James E. Molloy to shred the original list and three copies, including one made for Bishop Edward Cullen, a top aide who later led the Allentown diocese.

Hand-written notes state that Molloy did so in the presence of another aide, Bishop Joseph R. Cistone, who is now the bishop of Saginaw, Mich.

Yet a surviving copy surfaced at the archdiocese early this year — 10 days after Bevilacqua died.

The list was found in a gray file in Coyne’s office. But it had first been found in 2006 in a locked safe at the Secretary for Clergy’s office.

A staff person cleaning out the file room — in disarray after the grand jury investigation — came across the safe and had a locksmith open it, according to her testimony last week.

She said she found a gray file inside and left it with an assistant to Monsignor Timothy Senior, who had succeeded Lynn. Coyne testified that Senior later gave the file to him for safe keeping. He said he only glanced at it before putting it in his files, and didn’t realize it held the list he had sought years earlier.

On cross-examination from defense lawyer Thomas Bergstrom, Coyne acknowledged that Lynn had apparently looked for the list in 2004 after telling the grand jury about it.

“My impression is he looked everywhere for it,” Coyne said.

Bergstrom suggested the locked safe belonged to Molloy, Lynn’s supervisor.

The list only surfaced on Feb. 10, on the eve of Lynn’s trial. Bevilacqua had died Jan. 31 at age 88.

As church officials took the stand Monday, the gray file became a hot potato. Senior, now an auxiliary bishop in Philadelphia, denied ever touching it. Fr. James Oliver, Senior’s assistant and a canon lawyer, likewise said he didn’t recall handling it.

Prosecutors have called the archdiocese an “unindicted co-conspirator” in Lynn’s case. Bevilacqua, in 10 combative appearances before the grand jury in 2003 and 2004, denied any attempt to obstruct the investigation.

The jury is expected to get the case by Memorial Day, after three months of testimony. Lynn faces up to 28 years in prison if convicted.

A spokeswoman for Cistone referred a call for comment Monday to his lawyer, William Winning of Philadelphia, who did not immediately return a message. A message left through the Allentown diocese for Cullen, who retired in 2009, was not immediately returned. Molloy died in 2006.

The Philadelphia archdiocese is not commenting on trial developments because of a gag order.

Complete Article HERE!