Five years ago, a handful of Colorado legislators sought to make it easier for victims of decades-old sex abuse to sue their tormentors and the organizations that protected them.

The Archdiocese of Denver fought back hard.

The state’s Catholic hierarchy — through jeremiads delivered from the pulpit and alliance-building with municipal interest groups and teacher unions — turned an initially popular bill to extend the civil statute of limitations on sex crimes into something politically toxic. By the end of 2006, the bill was dead on the statehouse floor.

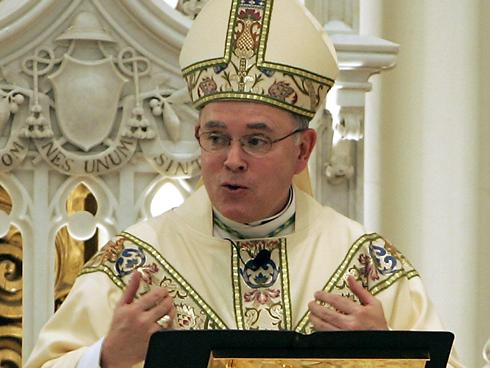

Archbishop Charles J. Chaput, then head of the state’s largest archdiocese, stood at the center of that debate.

His vocal opposition made him an enemy to victims’ groups, who viewed his political protest as a cunning effort to protect church coffers. But to those who saw their church as under siege from profiteers, Chaput emerged a hero.

‘‘They thought they were fighting for their lives,’’ said Annemarie Jensen, a political strategist who lobbied for the bill on behalf of the Colorado Coalition Against Sexual Assault. ‘‘It was about as ugly a political fight as I’ve been involved with at the Capitol.’’

Chaput — who is set to take the helm of Philadelphia’s archdiocese next month — says he was just doing his job.

‘‘The Catholic Church wants to be treated like citizens with equal access to protection of the law,’’ Chaput said at a news conference in Philadelphia last month. (The Denver Archdiocese did not make him available for an interview for this article.) ‘‘That’s all we were asking for in Colorado.’’

Little resistance

Since the nationwide church scandal began about a decade ago, five states have passed bills temporarily reopening the civil statute of limitations on sex-abuse cases. Eight others, including Pennsylvania, have considered them.

This so-called window legislation allows victims to seek justice years after their abuse by temporarily extending the period in which they can file claims. Although none of the adopted bills specifically mention the Catholic Church, archdioceses became the primary targets of litigation in each of the states that have passed them.

In California, one of the first to pass such legislation, more than 850 claims flooded courthouses during the one-year window that legislators opened, costing the church millions in damages and settlements.

The Diocese of Wilmington declared bankruptcy in 2009 after it was named in more than 175 suits following the state’s passing of a two-year window. Last month, a judge agreed to a reorganization plan that includes a $77.4 million settlement for clergy sexual abuse. Last week, the Oblates of St. Francis de Sales agreed to pay $24.8 million in suits filed by 39 survivors of priest sex abuse in Delaware.

But before the Colorado fight, Catholic bishops had responded to window bills with begrudging acceptance — such measures were seen as a necessary evil to heal the rifts clergy abuse had caused.

California’s church hierarchy barely pushed back when that state’s bill passed in 2002. In Ohio, bishops appealed to state lawmakers quietly and directly to help kill a bill in 2005.

Colorado’s bill, introduced in 2006, differed little from its predecessors elsewhere. It proposed lifting the statute of limitations on sex-abuse cases going forward and opening a two-year window for expired claims.

At that point, the Denver Archdiocese had had a relatively minor brush with the sex-abuse scandal involving fewer than 20 lawsuits with allegations involving only two priests. Chaput later offered victims in those cases a mediation process that resulted in $5.5 million to settle most of their claims.

‘A duty I can’t avoid’

But his response to the bill marked a sharp break. Chaput spoke out, condemning the legislation as ‘‘unfair, unequal, prejudicial,’’ and anti-Catholic. He took to the Catholic press, accusing colleagues in other states of acquiescing out of an overabundance of ‘‘guilt, confusion, and a desire to take what they perceive to be the ‘high road.’ ’’

‘‘I have an obligation — a duty I can’t avoid — both to help the victims and to defend innocent Catholics today from being victimized because of earlier sins in which they played no part,’’ he said in an interview that year with the national Catholic newspaper Our Sunday Visitor.

Marci Hamilton, a Bucks County, Pa., lawyer who has represented several victims of clergy abuse and whose 2008 book ‘‘Justice Denied’’ tracked statute-of-limitations fights across the country, described Chaput’s outspokenness as just the first element in the Denver Archdiocese’s multipronged opposition to the bill.

‘‘It was Chaput who decided public relations would change the course of this fight versus any other tactic,’’ she said. ‘‘Things changed with Chaput’s packaging in Colorado.’’

What separated the Denver Archdiocese’s response from those that had come before was its direct appeal to the public and a degree of savvy political maneuvering unseen elsewhere.

Within weeks of the bill’s introduction, Chaput sent a letter to all parishes to be read from the pulpit during Sunday Mass. The missive excoriated the legislation as unfairly targeting the Catholic Church while ignoring sex abuse in other institutions.

State Rep. Gwyn Green, a sponsor of the legislation, recalls jumping from the pew of her parish in the Denver suburbs the day the letter was read and objecting to what she described as a blatant misrepresentation of her bill.

Nearly 25,000 protest cards were distributed to those attending Masses, asking them to sign and mail them to their state representatives.

‘Full-blown war mode’

‘‘The archdiocese went into full-blown war mode,’’ said John Kane, a religion professor at Jesuit Regis University in Denver. ‘‘They worked through the parishes. They rallied straight from the altar. It was a full-court press in the media and everywhere else.’’

Behind the scenes, the church’s political arm, the Colorado Catholic Conference, hired one of the state’s top lobbying firms, owned by the former campaign manager of then-Gov. Bill Owens, to run the ground game on legislative votes.

It began by appealing to the Catholic faith of several top legislators and leaking stories to the media that plaintiff attorneys had helped craft the bill.

(The bill’s leading sponsor, Colorado Sen. Joan Fitz-Gerald, later opened her files to show she had had only minimal contact with plaintiff attorneys, including Hamilton.)

From the start, the archdiocese had characterized the proposals as unfair, noting they would affect private institutions such as the church but exempt governmental entities such as school districts.

School districts and other public institutions were protected under Colorado law by immunity from the worst of civil suits. State law gives plaintiffs six months after an incident to file claims and caps damages at $150,000.

Window-bill backers argued such limitations were appropriate because taxpayers funded these government entities, which were also required to share their files under open-records laws. Private institutions, meanwhile, could opt to shield records of abuse from public review.

But church lobbyists pushed. And by May 2006, they had persuaded Colorado lawmakers to alter the bill to subject government groups to the same $700,000 damages limit that private institutions would now face.

The battle is lost

In so doing, the bill’s backers unwittingly opened the door to its demise.

Teachers’ unions, lobbyists for local governments, and insurance companies soon joined the fight. And with mounting opposition from the capital’s most powerful interest groups, the bill that had sailed through committee months earlier suddenly was resoundingly voted down.

‘‘They boxed us into a corner,’’ Green said. ‘‘We had no moves left.’’

It remains difficult to ascertain exactly how involved Chaput was in developing this strategy.

Francis X. Maier, Chaput’s chancellor in Denver, maintained in an email that the archbishop played a minimal role.

‘‘There was nothing tactical or strategic about our approach,’’ he said. ‘‘The archbishop saw that it was a bad bill and said so.’’

Chaput’s influence can be seen in the final result. Tactics such as allying with unions and municipal leagues, direct appeals to the Catholic faithful, and refusing to simply concede to the state’s political powers all sprang from his speeches and writings at the time.

And in the years since, he and his staff have emerged as leading advisers to other archdioceses — including Wilmington — facing window bills in their states.

That has some Pennsylvania legislators worried.

State Reps. Mike McGeehan and Louise Williams Bishop filed bills in March that would eliminate the civil statute of limitations on childhood sex crimes and open a two-year window for filing expired civil claims.

On the heels of a damning grand-jury report outlining years of alleged abuse cover-ups in the Philadelphia Archdiocese, the Philadelphia Democrats hoped their legislation would coast through.

So far, though, they’ve seen only halting progress. Both bills remain stuck before the House Judiciary Committee with no hearing dates and no planned schedule to bring them to a vote.

Chaput’s arrival in Philadelphia next month will likely only complicate matters, Bishop said. Still, she remains hopeful.

‘‘I believe the tide is rolling in our direction,’’ she said. ‘‘I do believe there is a movement of sympathy for child sex-abuse victims.’’