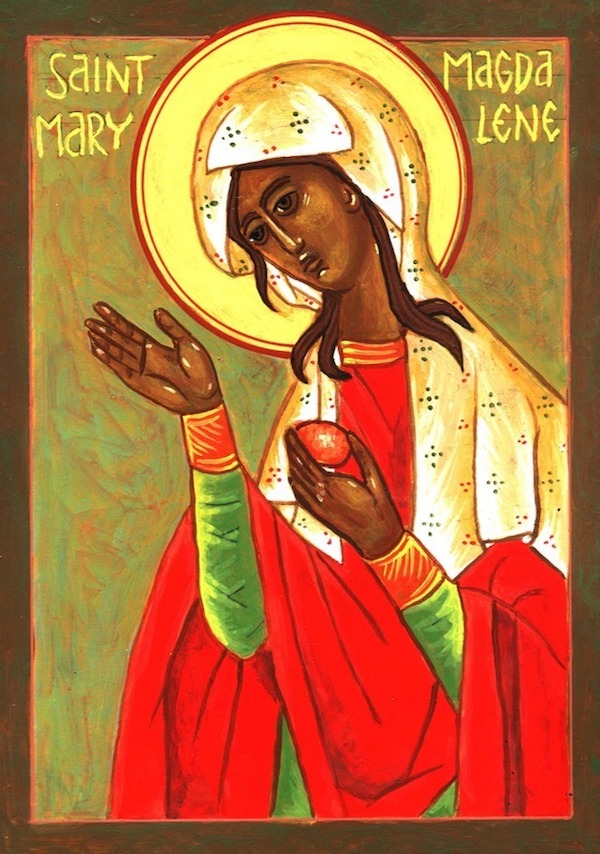

On 22 July each year, the Christian community venerates a saint who is the single best argument for why women should be priests: Mary of Magdala, more commonly called Mary Magdalene and traditionally known as the “Apostle to the Apostles.”

Given what we know about her, it’s a scandal that some Christian communities—most notably the Roman Catholic Church and the Southern Baptist Convention—still consider women unworthy of ordination.

The Roman Church’s refusal to ordain women is succinctly stated in its official Catechism:

The Lord Jesus chose men to form the college of the twelve apostles, and the apostles did the same when they chose collaborators to succeed them in their ministry…For this reason the ordination of women is not possible. #1577

The Southern Baptist Convention bases its refusal on several passages in the Pauline letters to Titus and Timothy that seem to disallow women from serving as pastors. (Never mind that biblical scholars agree that the letters were almost certainly not written by Paul himself.) Predictably, perhaps, the Convention adds that pastoral ministry would interfere with women’s single-minded dedication to their God-appointed “family roles.”

Such objections to the ordination of women strike rational people, including millions of Christians, as absurd. But Dominican priest Wojciech Giertych, who served as theologian of the papal household for Pope Benedict XVI, adds risibility to absurdity when he argues that women simply don’t have the mechanical know-how of men, and so would be helpless when it comes to guy-stuff like church repairs.

I don’t know how handy she was with a hammer or screwdriver, but the scriptural accounts of Mary Magdalene certainly confound these arguments against women priests and pastors. Her prominence in the New Testament is indisputable.

She’s presented as one of the earliest disciples of Jesus, joining his band of followers after being cleansed of “seven demons” (Mark and Luke). Although she actually isn’t the New Testament “sinner” who washed Jesus’ feet with her tears or anointed them with precious oil she’s often thought to be—this is an identification invented by Gregory the Great in the 6th century—she’s still mentioned more often in the Gospels, no fewer than 12 times, than nearly all the male apostles.

The gospels of Mark, Matthew, and John recognize her as one of the women who followed Jesus to Golgotha, when all the male apostles except John had fled in terror. All four gospels also announce that she was either the very first person (Mark and John) or one of the first (Matthew and Luke), her companions also being women, to whom the Risen Christ appeared, and that she was the messenger who carried the good news to the male apostles.

Luke tells us that the other disciples didn’t believe her, either because she was a woman or because the tale was so fantastical, and ran to see the empty tomb for themselves. In the apocryphal Gospel of Mary, dating from sometime in the 2nd century, the disbelief of the male apostles, especially the brothers Andrew and Peter, is clearly rancorous. “Did he then speak secretly with a woman, in preference to us, and not openly? Are we to turn back and all listen to her? Did he prefer her to us?” In the later Gospel of Philip, another apocryphal text, the anger directed against Mary by the male apostles is even more intense.

These texts suggest that even at this early stage in the Church’s history, animosity toward women in leadership positions was present. But the more important point here is that both canonical and non-canonical texts affirm Mary as the witness-bearer for the risen Christ. There simply is no debate in the ancient texts about her centrality.

We have nothing but legend to fall back on for the rest of Mary’s life. She isn’t mentioned in either the Acts of the Apostles or any of the New Testament epistles. Some stories say she retired to Ephesus with Mary, Jesus’ mother, after the Resurrection. Others say that she undertook missionary work, even appearing before the Roman emperor Tiberias and astounding him with a miracle.

But these legends, charming as they are, aren’t necessary for establishing her bona fides. Scripture does that. Mary Magdalene, like so many women, was one of Jesus’ earliest followers; she remained loyal to him, at great risk to herself, when the male apostles fled in doubt and terror; the Risen Christ appeared first to her; and she carried the good news to the male apostles, who refused to believe her testimony. Even John Paul II, who declared the topic of women’s ordination settled and done (a position unfortunately affirmed by Pope Francis), acknowledged that this rightly made her the Apostle to the Apostles.

So if men are qualified to ordained ministry because of the male apostles, wouldn’t Mary’s primacy over them qualify women?

The answer’s pretty clear, isn’t it?

Complete Article HERE!