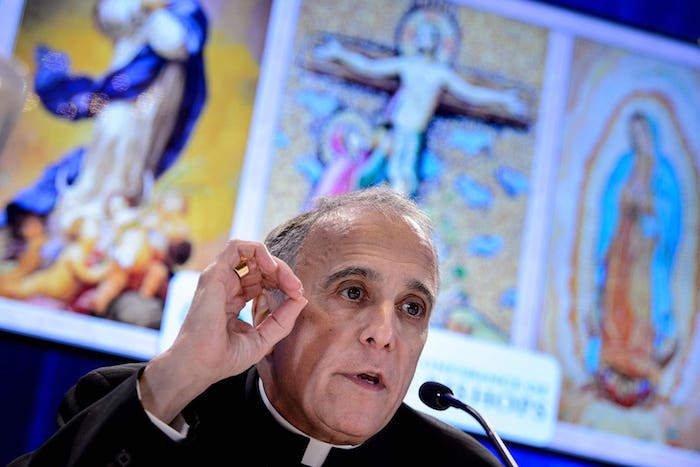

Ross Douthat and Massimo Faggioli argued over Francis’s legacy last week.

By Tara Isabella Burton

Two high-profile Catholic thought leaders duked it out last week in a debate over the five-year legacy of Pope Francis — and what his papacy means for a church in crisis.

Longtime intellectual rivals Villanova professor Massimo Faggioli and New York Times columnist Ross Douthat engaged in a conversation on Pope Francis, hosted by Fordham University in New York. The debate ultimately developed into a far broader question: How far should the church change in dialogue with modern sexual ethics when it comes to issues like women priests, divorce, abortion, and same-sex marriage?

And — perhaps even more importantly — the conversation turned broader still, as both participants asked if change should be seen as a theologically necessary part of the Catholic tradition.

Faggioli, a self-professed liberal Catholic, and Douthat, a conservative, have long expressed differing views on Francis’s papacy, and on the trajectory of the Catholic Church more generally through bold rhetoric on Twitter.

Since the beginning of Francis’s time as pope, much secular media attention has focused on what, to non-Catholics, have appeared to be relaxed stances on usually taboo issues for Catholics. Francis’s papacy, while changing little in terms of Catholic doctrine, has nevertheless made welcoming those who fail to follow that doctrine (whether on abortion, LGBTQ issues, or divorce) into the Catholic community a priority.

For example, Francis opened a temporary window for women who have had abortions to seek forgiveness from the church in 2015. One of his most famous early statements may have been asking “Who am I to judge?” when it comes to homosexuality, although Francis has elsewhere maintained traditional Catholic doctrine.

Douthat, a Catholic convert, has frequently been critical of what he deems Francis’s divisive tactics, including using unofficial or “leaked” communications to the media to informally express more controversial views. He also opposes a willingness to, in his view, upend church tradition for the sake of pacifying liberal attitudes and retaining church membership.

For his part, Faggioli, an admirer of the Francis pontificate, has frequently condemned Douthat as an intellectual dilettante, criticizing his lack of formal theological training and what he sees as Douthat’s partisan perspective on church issues.

Their personal disagreement masks a wider debate, not simply between “liberal” and “conservative” Catholics, or between “progressives” who want to change the church to fit contemporary cultural mores and “traditionalists” who want to preserve the church exactly as it was.

It’s a debate between those who see a degree of dynamism as already part and parcel of what it means to be Catholic, and those who see it as an exterior, dangerous force.

The debate on Francis is also a debate on the aftermath of Vatican II

Although Faggioli and Douthat’s debate was about the pope, it wasn’t just about the pope. Central to their disagreements were their perceptions of the effects of Vatican II (formally known as the Second Vatican Council of 1962-1965), which explored if and how the church should adapt to a changing world.

At that point, Catholics the world over were still responding to the aftermath of World War II, and the Holocaust in particular, leading some Catholics to question the language and tone with which the church approached interfaith issues.

Those changes under Vatican II included an increased focus on ecumenical relations, and on Catholic-Jewish relations. But the relative liberalization of Vatican II (for example, eschewing Latin during Mass) has often been seen by later critics as paving the way for an acceptance of more extreme elements of “modernity,” such as the sexual revolution. That movement challenged the formal Vatican positions on abortion, contraception, same-sex marriage, divorce, and premarital sex more generally.

Official church doctrine has never changed on any of these positions (nor, should it be noted, has even the “liberal” Pope Francis ever sought to change them).

Still, the “spirit of Vatican II,” or its overall ecumenical ethos, is cited by proponents and critics alike to refer to post-Vatican-II liberalizing tendencies that exceed the remit of Vatican II’s more narrow reforms. To Vatican II’s critics, a broad definition of this spirit is responsible for a more general “liberalization” in the church.

The subsequent half-century or so of the Catholic Church has been marked by various popes’ differing responses to and reckoning with Vatican II, its spirit, and the question of what “moving forward” even means within a Catholic context. That brings us to the current debate — last week’s and among Catholics in general — around Pope Francis’s somewhat lax views.

Faggioli and Douthat’s debate reflected broader divides

Douthat, a perhaps more natural debater, took a more aggressive approach, referring to a coming “schism” and a “civil war” in the church, and saying that Francis’s approach risked fomenting a “crisis of papal authority itself.”

Speaking specifically about Francis’s opening to providing communion to remarried couples, Douthat warned that, by relaxing rules around communion, Francis risked promulgating the idea that “the papacy allows for changes around these contested issues of sexual ethic,” and thus challenging the idea — central to Catholic theology — that the church’s continuity on issues remains unchanged.

Faggioli, though, rejected Douthat’s very premise. Focusing on continuity as a metric for a “good” pope, he says, and “looking at Catholic doctrine in terms of continuity or discontinuity, in my mind, assumes one thing: that Christianity, at some point … was complete.”

Furthermore, Faggioli said his assessment of Francis’s perspective centered not on doctrine but on pastoral care. The church need not change its teachings, he said, but rather ask itself, “What can the Catholic Church do to make the faithful able to receive sacraments?”

For Douthat, Pope Francis represents a break with tradition so profound that it risks rendering a fundamental principle of Catholic thought irrelevant: the idea that the church exists in continuity with its past traditions and perspectives.

Citing the case of allowing parish priests license to grant communion to remarried Catholics, which Francis has quietly campaigned for, Douthat argued that such a procedure would, in practice, vitiate the church’s teaching on the indissolubility of marriage (because, in Catholic tradition, marriage is seen as an irreversible sacrament between the couple and God, divorce is not seen as legitimate).

It is, for Douthat and other Catholic conservatives, a back-door form of Catholic-sanctioned divorce. By advocating for it and similar reforms, Francis, in Douthat’s view, represents a dangerous figure for the church: one too willing to cede ground to modern liberalism.

Faggioli, though, argued that Douthat’s perspective — of “continuity” and “discontinuity” within church tradition — was flawed and ahistoric. He pointed out that Francis is not seeking to allow divorce — something that would be a striking change in church teaching — but only advocating that divorced and remarried couples be allowed to receive the sacrament of communion — and thus participate fully in church life.

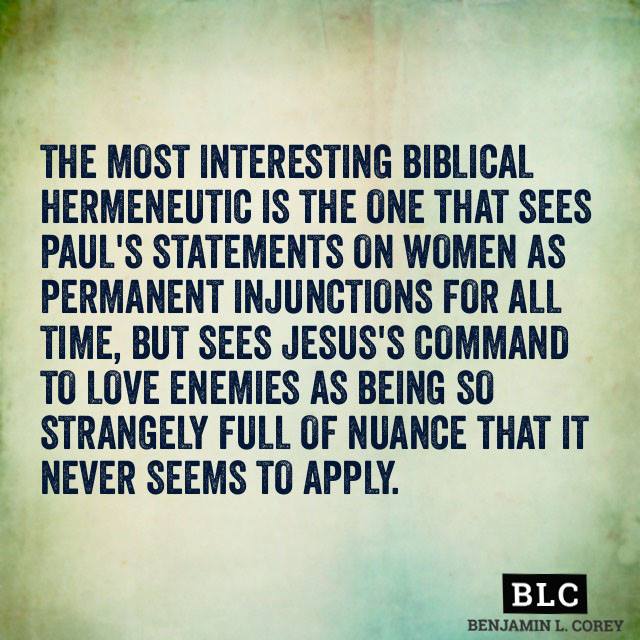

Instead, Faggioli said, Douthat’s view failed to reflect the way in which Catholic tradition has long existed in dialogue with itself, and how interpretations of Scripture have consistently grown and developed over time. The Catholic tradition, Faggioli said, “is not a mineral, it’s an animal. It moves. It adapts. It grows.”

Decades after Vatican II, the church faces demographic and social upheaval

While Douthat and Faggioli differ on the degree to which the Catholic Church is in danger, it’s fair to argue that it is — if not in crisis — at least in flux.

Decades of sex abuse scandals have eroded public trust in the ecclesiastical hierarchy. Mass attendance has drastically fallen in America and Europe, especially among young adults. There is an increasingly severe shortage of Catholic priests. And the face of Catholicism is changing, too. Catholicism is in decline in Western Europe and America, but drastically on the rise in Africa. Like it or not, the church is changing in demographics if not doctrine.

But the question remains: Where do we go from here?

The debaters’ differing perspectives may be as attributable to their methods as their politics. Douthat’s interest lies in the church as an institution; the questions he asks focus on that institution’s survival and transformation.

In many of his columns, as well as in his forthcoming book, To Change the Church?, Douthat approaches the church as a political scientist might, looking at how different conservative or modernizing factions have jockeyed for support and survival. His questions of “continuity” and “discontinuity” are questions one asks of an institution, rather than a faith.

Douthat comes to the study of the church as a zealous outsider, and that perspective — one that tends to see the church as a holistic, uniform body that, while sometimes under temporary threat, nevertheless remains intact — suffuses his work. That Francis seems to endanger that perceived unity makes him a threat.

Frequently during the debate, Douthat warned of the potential of a schism within the Catholic Church as a result of Francis’s developments: “Things can break … there is a deep conflict.”

Faggioli, however, is both a church historian and a trained theologian, whose concern is both with the church as an institution and with theology as a living, dynamic body of discourse, constantly being shaped by new questions and voices both inside and outside the academy.

As a theologian, he appears more comfortable with the often-murky process by which the exploration of ideas — theological debate — becomes calcified into church doctrine, and the way in which these ideas morph and change over time. Rather than arguing whether or not the church should adapt to shifting culture, he argued that a degree of dynamism is part and parcel of church tradition and always has been.

The Catholic Church’s priority should be on finding ways for the faithful to remain within the church, not expelling those who do not follow its teachings, he says. (And it’s important to stress, in this debate, neither Faggioli nor Francis is necessarily saying that its teachings should change. Faggioli’s point is about access, not ideas).

Both Douthat and Faggioli ask vital questions. And Douthat’s challenge — how does an institution address cultural change without losing its founding principles — is completely valid. Any answer that does not take seriously that for faithful Catholics, the doctrine being debated is a matter of weighty metaphysical truth, not just politics or optics, fails to appreciate the gravity of the question being asked.

Faggioli’s response — that “in order to get close to Jesus, there has to be some kind of discontinuity” — may provide “liberal” Catholics a viable alternative to Douthat’s reactionary historicism, and a way forward for a church that is both weighed down and grounded by its past.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!