I am delighted that my research and I are referenced in this fine article.

By Dani Garavelli

LOOKING back from a distance of more than 20 years, Fr Joe can see that his decision to join the priesthood was motivated in part by his homosexuality. Coming of age in the 1970s, when there was still a huge stigma attached to coming out as gay, it provided an alternative to getting married and having children.

“I was hugely idealistic and genuinely believed in the priesthood, but I think it was also the only respectable way to be Catholic and single,” he says. “I wouldn’t have recognised it at the time, but I think I was trying to escape having to tell my family about my sexuality or even having to face up to it properly myself.”

“I was hugely idealistic and genuinely believed in the priesthood, but I think it was also the only respectable way to be Catholic and single,” he says. “I wouldn’t have recognised it at the time, but I think I was trying to escape having to tell my family about my sexuality or even having to face up to it properly myself.”

Once ordained, however, he realised being gay in a church which considers homosexuality to be intrinsically disordered brings problems of its own. Prey to the same temptations as everyone else, but unable to talk openly about them, many homosexual priests find themselves feeling undervalued and isolated. Trying to navigate their way in a highly sexualised society, with little or no pastoral support, it’s hardly surprising if they sometimes find it difficult to keep their vows.

“I think celibacy is always a struggle, it’s the same for all priests – in fact it’s the same for married people – you try to keep your integrity, to stay true to what you have been called to, ” says Fr Joe, who was a priest in Scotland but has now moved abroad. “I belong to a religious order that means you live with other guys; it means you have emotional support and your chances of being lonely are less. The ones I feel really sorry for are the diocesan priests who are alone in a parish. I think celibacy must be even more difficult for them. They have no-one to confide in when they are feeling low or horny or any other normal human way of feeling.”

As with any same-sex environment, such as a boarding school or prison, there can also be a kind of “super-heated effect” in the seminary or church where, regardless of sexual orientation, men have crushes on other men and that is more likely to spill over into sexual behaviour when the whole subject of sexuality is taboo. “I think that is something gay men in the Church are prone to,” Fr Joe says. “Because the subject is hidden, it creates this secret club kind of environment because priests who are gay are only likely to be open with other priests who are gay, you become part of a secret club, not because you want to, but because your peers are your support group.”

Fr Joe’s experiences are not rare. Studies have suggested the priesthood attracts a disproportionate number of gay men, with Dominican Friar-turned-journalist Mark Dowd suggesting earlier this week, the figure could be as high as 50 per cent. Such statistics have become headline news because even as the Church has become increasingly strident in its position on such issues as gay marriage it is being claimed that an increasing number of homosexual priests, Bishops and even Cardinals are breaking their vow of chastity.

There have, of course, been many scandals in the past involving heterosexual priests and Bishops, who have had affairs and fathered children. But now Italian newspapers are speculating Benedict XVI’s unprecedented resignation was inspired by a dossier revealing a powerful network of actively gay priests in the highest echelons of the Vatican. The dossier was compiled in the wake of the Vatileaks scandal, which saw papers taken from the Pope’s desk published in a blockbuster book, and after Italian journalist Carmelo Abbate took a hidden camera into Rome’s gay nightclubs to expose a group of priests who said mass by day and had sex with male escorts by night.

Back at home, there have been controversies too. In 2008, a man was jailed for blackmailing a priest he had encountered at a meeting point for gay men in Kelvingrove Park in Glasgow. And now, of course, there are the allegations that Cardinal Keith O’Brien engaged in “inappropriate behaviour” with several priests, allegations which, though contested, led him to step down.

From a secular viewpoint, the scandal lies less in the sexuality of the priests, but in the perceived hypocrisy of an institution which is seen as homophobic being an apparent cauldron of gay activity. But this contradiction also raises questions as to the degree to which the Catholic Church’s attitude towards homosexuality – and the climate of secrecy it engenders amongst gay priests – has contributed to its own travails.

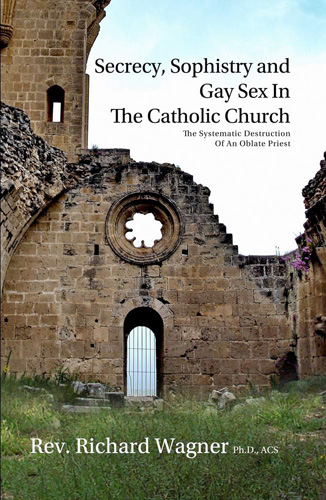

The fact the priesthood is attractive to homosexuals is neither new nor surprising. Neither are the Church’s efforts to cover this up. Back in the 1980s, Richard Wagner, an openly gay priest from Illinois, who was completing a doctorate in human sexuality, interviewed 50 gay priests about their experiences in order to examine how they reconciled their own identity with the Church’s absolute ban on homosexual activity. As a result of the media firestorm surrounding the publication of his dissertation “Gay Catholic Priests: A Study Of Cognitive And Affective Dissonance”, he says he was hounded out of his religious order. “In one way, the Church is the perfect place for closeted homosexual to prosper,” he says. “But at some point, these people have to face their sexuality and either address it and become comfortable with it or have it contaminate the rest of their lives. When you live in the confines of the seminary there’s not the same kind of distraction you have when, after ordination, you are in ministry in a world awash with sexual imagery. Hopefully that washes over those who are healthy and integrated in terms of their sexuality, but those who are troubled are lost. I was merely pointing out there was a significant population of gay priests, good men who had committed their lives to the Church, who were struggling with their sexuality and there was no encouragement or help.”

The atmosphere such isolation fosters, the deep-seated shame it engenders, lends itself to exactly the kind of abuses of power or inappropriate behaviour O’Brien has been accused of. “A combination of the Church’s immature attitude to sex and the secrecy of the gay priest is a really powerful, really poisonous mix,” Fr Joe says.

The irony is that as society as a whole has become more accepting of homosexuality (and recent research suggests the Catholic laity is less concerned about issues like premarital and gay sex than other Christian denominations), the Church’s position has become more entrenched, with O’Brien, originally perceived as a liberal, at the vanguard of the campaign against same-sex marriage.

“They say their job is not to reflect society, but to challenge society, but I think the Church has lost its moral authority to speak about homosexuality because it has shown so little tolerance of and support for gay and lesbian people,” says Fr Joe, who went out of his way to ensure his Scottish parish was inclusive. “It says, ‘Oh it’s not the sinner we hate, it’s the sin,’ but to my mind, that’s rank hypocrisy.”

In the wake of the succession of sex abuse scandals which has shaken the Church over the past 10 years, the hierarchy tried to clamp down on the ordination of gay priests – a move which was hugely controversial, not only because of the hurt it caused existing gay priests, but also because it implied a connection between homosexuality and paedophilia.

Under the new policy, introduced in 2005, men with “transitory” homosexual leanings could be ordained following three years of chastity, but men with “deeply rooted” homosexual tendencies or those who were sexually active could not. The Church also introduced a tougher screening process. Many candidates for the priesthood in England and Wales, for example, are sent to St Luke’s Centre in Manchester, where they are subjected to a battery of psychological tests.

The sense they are not wanted has made existing gay priests feel even more demoralised. “There’s been a constant drip, drip, drip of negativity, taking away guys’ self-esteem, coming from this hypocritical section of the Church,” Fr Joe says.

Today Wagner runs a website and receives calls from troubled gay priests all over the world. Some of them, he says, want to lead the ascetic life they signed up for, others are looking for sexual fulfilment, but all are trying to reconcile two conflicting parts of their own personality – their vocation and their sexuality.

“They want to know how to navigate this maelstrom of sexual negativity and try to put that together with the Gospel message of authenticity and integrity and truthfulness, but it’s nearly impossible to do,” he says.

The fact that some highly placed gay clergymen endorse the Church’s line on homosexuality could be viewed as the height of cynicism, but others, who have seen the workings of the Church at close hand see it as a manifestation of their inner conflict. “There are a lot of self-hating priests, but there are others who are frightened – they feel they have to toe the line or they will be out of a living,” says Fr Joe.

Vatican adviser John Haldane has suggested one way out of the current crisis is to compel priests – gay or heterosexual – to renew their vow of celibacy or leave the Church. Yet it is hard to feel anything but sympathy for committed priests who took their vows before they really understood their own sexuality or how important the need for companionship might become in later life. “There are men who think they can take this vow and live up to it, especially if they are fairly young,” says Elena Curti, deputy editor of The Tablet. “They are full of enthusiasm and idealism and they can survive on that for the first decade or two, but in my experience, when they get older, into their 40s and 50s, they feel immensely isolated. They see their peers around them with children and a real, intense loneliness kicks in and it’s often at that stage they stage they leave.”

Since the Church can’t afford to lose any more clergy, it seems more sensible to relax the rules on marriage as O’Brien suggested days before he resigned. Celibacy is not a matter of doctrine and there are many liberals who would be happy to see it dropped. This feeling has been strengthened by the Church’s decision to welcome married Anglican priests into the fold. But relaxing the rule on celibacy would not help ease the plight of gay priests; if anything it would make it worse. They would have to continue to battle with their own sexuality while watching their peers enjoy loving relationships.

Fr Joe is realistic; he knows whoever becomes Pope, the Church’s attitude towards homosexuality is unlikely to be radically overhauled in the near future. So what changes would he like to see? “The first thing and the easiest thing in the world, is a change of tone. Notch the warmth up 10 degrees and stop talking about homosexuality in terms of sin and disorder,” he says. “Secondly if the Church wants authority to speak on that matter it needs to show a clear level of pastoral support for lesbian and gay people that is non-judgmental on a spiritual and practical level.

“Then you it look at how the doctrine of the Church is expressed – whether it accurately reflects a good understanding of anthropology or sociology or psychology, or whether the Church is operating from an outdated model.” Fr Joe says that’s a 100-year project. But one thing’s for sure, unless the Church starts to address the disparity between the homophobia it spouts and the conduct of its own priests soon, the new Pope is likely spend his time in the Vatican as his predecessor did – firefighting one sex scandal after another.

Complete Article HERE!