Dr Fran Fisher’s latest book blows the lid off the repressed sexuality of convent life. And it’s a subject the former nun knows first hand

By Joanna Moorhead

From nun to sex therapist isn’t an obvious career path but, says the former Sister Jane Frances de Chantal, “when you’ve been starved for a while, you certainly appreciate the feast at the end of it”.

In the Name of God, Why?: Ex-Catholic Nuns Speak Out about Sexual Repression, Abuse & Ultimate Liberation by Dr. Fran Fisher

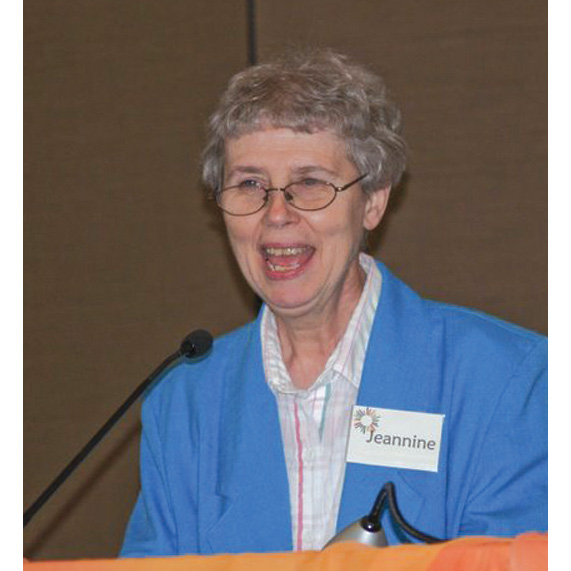

Today, Sister Jane is Dr Fran Fisher, a California “sexologist” in US-speak. But she was born and raised in Yorkshire and entered a Franciscan convent in Derbyshire aged 18. She left two years later, met and married an academic, and moved to the US. It wasn’t until she was in her 40s, she says, that she began to understand how much her Catholic upbringing, and her experience of being a nun, had damaged her sexual instincts.

Today, Sister Jane is Dr Fran Fisher, a California “sexologist” in US-speak. But she was born and raised in Yorkshire and entered a Franciscan convent in Derbyshire aged 18. She left two years later, met and married an academic, and moved to the US. It wasn’t until she was in her 40s, she says, that she began to understand how much her Catholic upbringing, and her experience of being a nun, had damaged her sexual instincts.

With her children growing up, she saw a course in sex therapy advertised and her interest was immediately piqued. “I enrolled, and what happened next blew my head off. One day the tutor said we were going to discuss our masturbation history and I thought, can I really do this? Somewhere inside I was still a nun even after all these years … I was still sexually naive. I realised that the legacy of my time in the convent was the cause of most of the problems in my marriage. It had been drummed into me as a novice that I didn’t really have ownership over anything, even my own body.”

Fisher decided to combine her new professional direction, running workshops and counselling, with her own past, and to find out whether other former nuns had had similar experiences: the result is a book in which she interviews 28 women who, like her, took vows of poverty, chastity and obedience only to later leave orders. She talked to them about their sexuality before, during and after their time in the convent and discovered many similarities. “Most of the women I interviewed had been raised in strict Catholic families. Many had an alcoholic father. Quite a few had a history of physical and/or sexual abuse. A lot of them described the convent as a safe place to go.”

Fisher, who is now in her early 60s, realised that some of the traits of her own childhood were typical – in particular the fact that both her Irish Catholic parents had wholly negative attitudes towards sex. Her father, she says, almost always described women in pejorative terms; her mother, meanwhile, thought sex was “dangerous, dirty, vile, nasty and filthy”. When Fisher, then aged 14, feared she was pregnant – after an episode of petting that didn’t involve intercourse – her mother fuelled her fears, leaving her with a sense of “never wanting to have anything to do with a man again”.

The convent had the allure of a place where women were pure and mysterious and – most importantly – safe. But once inside its walls, her sexuality began to surface. Fisher became increasingly unhappy, lost a lot of weight, and eventually left the convent one Saturday morning while all the other sisters were at mass. She was, she says, still as naive about sex as she was when she arrived. But that wasn’t the case with all the women she interviewed. “Those who spent decades in a convent had usually experienced a sexual awakening. Some had relationships with other nuns, some with priests, some with laypeople.”

Some of them, too, talked to Fisher about how they were aware of sexual abuse that was going on in the Catholic church – but most, she says, were unable or unwilling to do anything about it. “Very few nuns were whistle-blowers,” she says. “When you’re a nun, you give away your ability to judge a situation.” Obedience meant not taking the lead and not questioning those who were obviously in positions of authority – such as male priests.

Some of them, too, talked to Fisher about how they were aware of sexual abuse that was going on in the Catholic church – but most, she says, were unable or unwilling to do anything about it. “Very few nuns were whistle-blowers,” she says. “When you’re a nun, you give away your ability to judge a situation.” Obedience meant not taking the lead and not questioning those who were obviously in positions of authority – such as male priests.

Some of the women in the book describe exploitative and unequal sexual relationships with priests – relationships they later questioned but which, at the time, they accepted as “necessary” for the men. As for having a healthy, “normal” sexual relationship, some of the women Fisher interviewed were middle-aged before this happened for the first time. “One woman described having intercourse for the first time aged 52. Another told me that when she first got a boyfriend, aged 50, she had sex every night for the first two or three months. Her partner thought he was going out with an Amazonian – but she said to him: “I’ve waited half a century for this, just lie back and shut up!'”

Fisher, like some of those she interviewed, did eventually experience a happy and more typical sex life. But she is fiercely critical of the Catholic system that allows naive young women (these days, more usually they are from Africa or Asia rather than Europe or North America) to uproot themselves from their families and enter a convent.

“The practice of taking young women (or men) from a childhood of indoctrination and expecting them to make a lifelong commitment to celibacy in their early 20s is clearly wrong,” she says. “And it’s still going on. Not long ago, I saw some young nuns being interviewed on TV. I saw their faces, and I thought: it’s still happening. There are still young women in some parts of the world for whom a convent offers a sanctuary from difficult questions about sex, an education, opportunities. But it’s running away from life, and there’s a huge toll in terms of individual fallout down the line. The church shouldn’t allow it to happen.”

Complete Article HERE!