William Lynch, who beat the Catholic priest he said molested him as a child, is acquitted on elder abuse and felony assault charges. He may be retried on a misdemeanor assault charge.

SAN JOSE — A jury has found a San Francisco man not guilty of felony assault and felony elder abuse, despite his admission that he attacked the priest accused of molesting him nearly four decades ago.

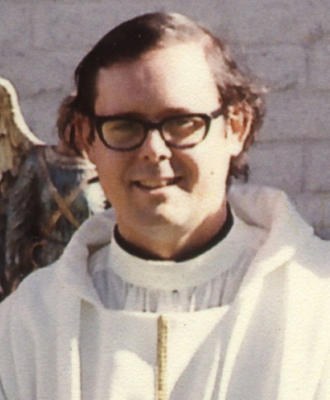

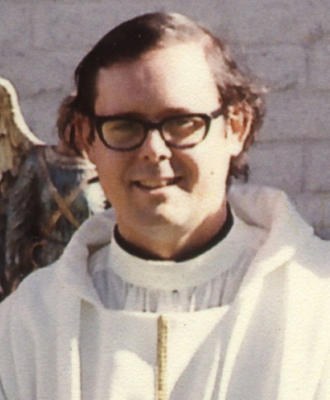

The 10-man, two-woman panel also said Thursday that William Lynch was not guilty of misdemeanor elder abuse in the 2010 attack on Father Jerold Lindner. The 67-year-old Catholic priest has been linked to more than a dozen alleged victims — including his own nieces, nephew and sister — but never has been brought to trial because the statute of limitations in every case had run out.

The 10-man, two-woman panel also said Thursday that William Lynch was not guilty of misdemeanor elder abuse in the 2010 attack on Father Jerold Lindner. The 67-year-old Catholic priest has been linked to more than a dozen alleged victims — including his own nieces, nephew and sister — but never has been brought to trial because the statute of limitations in every case had run out.

The jury was split on a final charge against Lynch: misdemeanor assault. Santa Clara County Superior Court Judge David Cena declared a mistrial on that count. Dist. Atty. Jeffrey Rosen said his office would decide in the coming days whether to retry Lynch.

After the verdict was read, Lynch said he had felt certain that he would be going to jail — and was pleasantly surprised that he would not. But he also spoke haltingly, and with deep emotion, about justice and responsibility.

“I was wrong for what I did,” said Lynch, 45. “If I’m going to be taking responsibility, I have to take it fully. And in [beating Lindner] … I was perpetuating the cycle of violence.”

Surrounded by family, supporters and his attorneys in front of the courthouse, Lynch said: “I wanted to … be accountable, unlike the church and Father Jerry up to this point.”

Rosen said that his office too had had a responsibility: to charge Lynch for lying his way into the Sacred Heart Jesuit Center, where the retired Lindner lived, and attacking him.

Using “a fake name, gloves. Beating and bloodying someone. That’s not justice under the law,” Rosen said after the verdict, giving a shorthand account of Lynch’s actions. “That’s revenge.”

Rosen said that although his office understood what motivated Lynch’s behavior, “we do not condone it.… A just punishment is delivered through our justice system, not through the acts of one traumatized and troubled man.”

The two-week-long trial was filled with dramatic turns and punctuated with tearful, graphic testimony — not about the attack in question, but about what happened in 1974. That is when Lindner allegedly lured Lynch and his younger brother, then 7 and 4, into his tent during a Catholic family camping trip. The boys said that the priest raped them and forced them to perform oral copulation on each other while he watched.

As the trial opened, Deputy Dist. Atty. Vicki Gemetti told the jury that Lindner, who was a spiritual advisor for the outing in the Santa Cruz Mountains, had indeed molested the Lynch brothers.

She played a gut-wrenching video of a San Jose Mercury News interview in which Lynch recently talked in graphic detail about that camping trip years ago. Gemetti told the jury that Lindner would “probably lie” when he took the stand.

When Gemetti asked whether he had molested Lynch and his brother, Lindner said: “No.”

Defense attorneys called for a mistrial, insisting Gemetti had committed prosecutorial misconduct by inducing perjury. Cena disagreed, and the trial continued.

But when Lindner returned to the stand, he refused to testify further on the grounds that he might incriminate himself. The judge then struck Lindner’s testimony entirely and told the jury to ignore the priest’s description of Lynch’s “vicious” attack.

And that, Juror No. 12 said, was key for him in deciding the case.

“The victim in this case disappeared,” said the retired accountant, who declined to give his name. “His testimony disappeared. To me, if you have no victim, do you have a crime?”

The juror, who walked with a cane and sported a silver brush cut, described the nine hours of jury deliberations over three days as cordial and professional.

“There were 12 people who simply agreed to disagree,” the juror said. “There was some disagreement with the law. There was disagreement with some of the testimony. There was disagreement with each other.”

The juror said that everyone on the panel believed that Lindner had committed “absolutely heinous” crimes against Lynch and his brother. But, he said, he was one of the eight who voted “guilty” on the lesser charge of simple misdemeanor assault because Lynch “got up and said he did it.”

To defense attorneys Pat Harris and Paul Mones, Lynch’s testimony was an act of courage fueled by his desire to protect other children from Lindner — and to fight the Roman Catholic Church and other institutions that cover up child sexual abuse and protect perpetrators.

“Will had the strength to speak for many people who can’t speak,” said Mones, who called the jury’s verdict “an example of what’s been happening around the country today.”

Complete Article HERE!

The Gallup Independent reports that the men will receive money as part of the settlement from the priest who is accused of sexually abusing them, the Diocese of Gallup, the Franciscan Province of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Albuquerque and another church entity.

The Gallup Independent reports that the men will receive money as part of the settlement from the priest who is accused of sexually abusing them, the Diocese of Gallup, the Franciscan Province of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Albuquerque and another church entity.