In May 1993, just outside the airport in the west Mexican city of Guadalajara, Juan Jesus Cardinal Posadas Ocampo was sitting in his parked white Mercury Grand Marquis when three vehicles packed with gunmen pulled up alongside and opened fire. The cardinal’s car was riddled with 26 bullets, and a nearby vehicle was apparently hit 20 more times.

Cardinal Posadas, his driver, and five others were found dead.

The high-profile assassination of one of the Mexico’s two Roman Catholic cardinals offers a window into the complex relationship between the Vatican and Mexico’s drug cartels. Cardinal Posadas was an outspoken critic of the groups and the violent terror they use to control Mexico’s illicit drug economy. Though the government ruled that his death was a case of mistaken identity, many still believe the killing was deliberate—that is, a successful attempt to silence him.

The man was wearing his clerical robes, after all.

Since Posadas’s death, and in particular over the past decade or so, the church has exercised top-down dealings with the cartels—condemning them in public, but, critics charge, colluding with drug criminals on the ground. Pope Francis spoke to that fraught dynamic during his historic visit to Mexico last week. In a sermon in the Michoacán state capital Morelia, which has been hit hard by cartel violence, he cautioned bishops, priests, nuns, and seminarians against shirking away from the unique challenge posed by the cartels in their area.

“What is the temptation that we face in environments dominated by violence, corruption, drug trafficking, disrespect for personal dignity, and indifference to suffering?” he asked, before answering his own question. “Resignation. Resignation terrifies us and makes us barricade ourselves in our vestries.”

That alleged resignation has long plagued the Catholic Church in Mexico, and though they weren’t named directly by Francis, no discussion of the cartel-church relationship would be complete without mention of “narco alms”—or blood money supposedly offered by cartels to help fund public works and other church activities. Cartel influence in the church was condemned by Pope Benedict XVI in 2005 shortly after he began his papacy, but the Vatican’s emphasis on the problem seems to have waned since. In 2010, a minor scandal erupted when it was revealed that a church with a stunning 65-foot high metal cross in the working-class barrio of the central Mexican city of Pachuca bore a plaque thanking Heriberto Lazcano, alleged kingpin of the Zetas cartel, for its construction.

As a result, the church began looking more carefully into “narco alms,” as the New York Timesreported in 2011.

It can be hard to resist the money and the help from cartels, particularly when murderous kidnappers are involved. Take for instance, the tale, also about the Zeta cartel, from Brooklyn-born priest Robert Coogan, who used to run a tiny prison chapel in the northern Mexico. As he told the Guardian in 2012, when Zeta prisoners offered to help paint his modest chapel, he declined, telling them a leaky roof would surely ruin their work. They not only completed the job but waterproofed the building too. “Making a fuss,” he said, “could have triggered reprisals against other prisoners.”

Today, it’s still awful hard being a church figure in a region where cartels wield so much power and influence; Mexico has replaced Colombia as the world’s most dangerous place to be a priest, according to the Catholic Media Center. After speaking out against the cartels, one priest named Gregorio Lopez received so many death threats he famously began wearing a bulletproof vest during mass.

Francis also addressed the citizens of Mexico on his trip, warning them, “Don’t let yourselves be corrupted by trivial materialism, or the seductive illusion of deals made below the table.” He urged ordinary Mexicans not to fall prey to the trap of pursuing money, fame, and power. “These are temptations that seek to degrade and destroy.”

The pope clearly recognizes that the downtrodden are particularly vulnerable to the temptation of violent crime in hopes that it might better their own lives.

“Throughout Latin America and the Caribbean, we have the massive divide between the rich and poor,” Henry Louis Taylor Jr., director of the Center for Urban Studies at the University of Buffalo, told VICE. “In Mexico and other places, the economy does not produce sufficient jobs for people to make ends meet. So most of them are forced to work in the informal economy—or in the clandestine economy. In those countries, corruption and bribery have been interwoven into the daily life and culture.”

Taylor Jr. believes you can’t stop stop the violence in places like Michoacán without radically changing the economy and offering alternatives. “In places where the cartels are entrenched, I don’t think the authorities are willing to do this.”

A couple years ago, armed vigilante groups emerged that seemed to take on the cartels before being at least partially infiltrated by them, as the in-depth Oscar-nominated documentaryCartel Land (which VICE helped distribute) shows.

“The pope expressed the views of so many people in Mexico,” Cartel Land director Matthew Heineman tells VICE. “But the tragedy is that their views and hopes for order and security have been ignored for so long by a government that has allowed the cartels to operate with impunity, resulting in a vicious cycle of violence for so many.”

Some believe the Catholic Church still needs to do more, perhaps even excommunicating those who affiliate with cartel members. After all, Pope Francis did travel to southern Italy to excommunicate members of the mafia in 2014. “The hierarchy of the church in Mexico has been timid when it comes to narco traffickers but that could change,” religious scholar Elio Masferrer told TIME earlier this month. “An action such as excommunicating them could have a significant impact.”

One might argue Mexican cartels are much more powerful—or at least more brazen—than the Italian mafia in 2016. But it’s not insignificant that the church’s top figure, a man who commands respect in Mexican cities plagued by drug violence, is speaking plainly and forcibly about the cartels. (At one point, Pope Francis went so far as to dub them “dealers of death.”) What remains to be seen is whether a relatively new pope and a government that did manage to recapture Sinaloa cartel boss El Chapo after his escape from prison this summer can put some real distance between spiritual matters and the drug money coursing through Latin America.

Complete Article HERE!

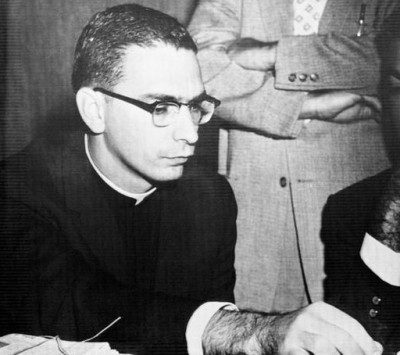

John Feit, 83, had long been the main suspect in the 1960 death of schoolteacher Irene Garza, but he wasn’t arrested until Tuesday in Scottsdale, Arizona.

John Feit, 83, had long been the main suspect in the 1960 death of schoolteacher Irene Garza, but he wasn’t arrested until Tuesday in Scottsdale, Arizona.

“That was 13 years ago,” he said. “I’m totally puzzled by something coming up now, after the fact.”

“That was 13 years ago,” he said. “I’m totally puzzled by something coming up now, after the fact.”