A new report identifies 212 priests accused of sexual abuse in the Oakland, San Francisco, and San Jose dioceses.

By Emily Moon

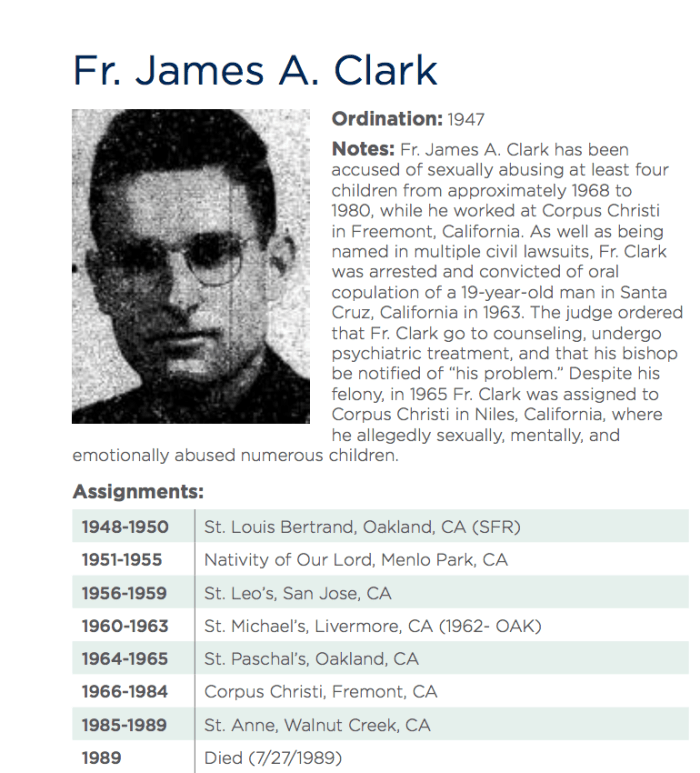

When Dan McNevin was nine years old, he served as an altar boy to Father James Clark in Corpus Christi Church in Fremont, California. There he worshipped alongside generations of his Irish Catholic family, attending mass and answering phones for the parish office. At first, says McNevin, now 60, Clark was “grooming him.” But soon the priest began to abuse him both physically and emotionally, undressing, touching, and assaulting him. He didn’t tell anyone, including his parents, for more than a decade. After three years, McNevin left the church forever; Clark did not.

Decades later, McNevin, then in his forties, confronted Clark’s superiors in the Oakland diocese, which governs all Catholic churches in the Alameda and Contra Costa counties, including Fremont. He says the area bishop told him the priest did not have a history of abuse, although he was a convicted sex offender, and denied shuffling him between posts (one way the Catholic church protects alleged abusers). McNevin believed the diocese—until he learned that the leaders of the same diocese had transferred a different offender 11 times. Then, in 2002, he met a survivor who had been molested by Clark five years after his own abuse. “I knew I got lied to,” he says. McNevin sued the Oakland diocese alongside several other victims, settling in 2005.

He works now as an area leader for the Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests (SNAP), a grassroots non-profit organization dedicated to helping victims of clergy abuse deal with their trauma. For survivors who’ve kept their abuse secret, media coverage publicizing the offender’s crimes can be both triggering and validating. It’s a duality McNevin is himself familiar with: He still remembers the first time he saw his abuser’s name in print—once when he sued the church, later when he was quoted in an article detailing the church’s complicity in Clark’s crimes. The most recent of these came earlier this week, when the law firm Anderson & Associates published a report identifying 212 priests accused of sexual abuse in the Oakland, San Francisco, and San Jose dioceses.

“It’s validating to see his name yet again in lights,” McNevin says. This time, Clark’s name was included in a list of hundreds of alleged abusers, published for all of California to see. Advocates say compiling names—even those previously known—can help identify patterns of clergy sex abuse and cover-up. “It is believed that the Bay Area Dioceses do not make available to the public the full history, knowledge, and context of the sexually abusive clerics,” the firm wrote in the report. “This report is intended to raise awareness.”

The work histories compiled in the firm’s report show that, after Clark’s felony charge in 1963, the priest was reassigned three times. This is how he ended up at McNevin’s Fremont church, where he “allegedly sexually, mentally, and emotionally abused numerous children,” the report says. Between 1948 and his death in 1989, he had been moved to seven different posts across the state.

In the months after the Pennsylvania grand jury report put clergy abuse back in the national spotlight, Anderson & Associates has been leading the effort to name names in California, home to more than 10 million Catholics. The Minnesota-based firm published another report in early October, accusing 307 priests of abuse in Los Angeles. It’s also representing survivor Tom Emens, who filed a civil lawsuit this month against 11 dioceses, naming every single bishop in the state of California.

“This lawsuit is designed to require each of them to come clean, to actually tell the truth about what they know,” attorney Jeff Anderson said in a press conference on Tuesday. He called the cover-up of clergy sex abuse in California, where parishes relocated some abusers more than 20 times, “a conspiracy of silence and secrecy.”

The inner workings of this conspiracy are extensive, Anderson says: Some bishops have chosen to believe priests over their victims; work histories show the movement of abusers across the state, many with prior convictions; and the Vatican has long compelled its dioceses to secrecy.

The Bay Area list more than doubles the number of abusers that the three dioceses have so far acknowledged, according to SNAP. And yet lawyers and advocates agree it’s still far too low. The majority of incidences of sexual assault go unreported, and that’s especially true in the case of clergy abuse. (The Pennsylvania investigation found that up to 8 percent of priests in the state abused children.) But research shows most survivors of clergy sex abuse wait decades to report, if at all; many face stigma and fear of backlash in their community, as well as the ongoing trauma of abuse, and, often, a crisis of religious belief. One 2008 study found that less than 5 percent of cases were reported within a year. In California, where 29 percent of the population is Catholic, McNevin estimates that as many as 2,000 priests could have abused thousands of children.

Some bishops have already tried to downplay these numbers by claiming they are not responsible for the actions of order priests, such as Jesuits or the Franciscans, who were working and living in the diocese at the time of abuse. “The alleged incidents occurred, and the reports of abuse were made, in other jurisdictions and were not shared with the Diocese of San Jose,” the diocese said in a statement on Wednesday, the Mercury News reports. Anderson, meanwhile, says his firm will push back on this excuse. “That is a deceit and a deflection,” he says.

Bay Area Priest Abuse Report by on Scribd

The church also argues that few of these names are new. All of the information in Anderson’s report comes from public records, when dioceses were forced to disclose the identities of offenders in 2002. Most of the allegations, the report says, have not been “proved or substantiated in a court of law.”

But much of this abuse has been common knowledge in the Catholic community for years, says Melanie Sakoda, a Bay Area volunteer with SNAP. She believes the renewed attention could have a real impact, either forcing the church to disclose more information, drawing out more survivors, or prompting an attorney general investigation like the one in Pennsylvania, which uncovered 300 abusers and thousands of victims. (A spokesperson for California Attorney General Xavier Becerra says it cannot “comment on, even to confirm or deny, a potential or ongoing investigation,” although local reports in San Jose suggest Becerra is looking into investigating the issue.)

While some trauma stems from ensuing media coverage around highly publicized issues of abuse, publishing names can also be an important part of the healing process. “When a survivor sees the name of his or her molester named, that person begins to experience some validation,” McNevin says. “That might cause them to report what happened to them. That report, in turn, attracts other reports, which eventually snowballs into a virtuous cycle for survivors of clergy sex abuse.”

Tom Emens, suing bishops across the state, hopes to kickstart this cycle. Standing beside Anderson at the press conference, he told those listening, including Sakoda and other members of SNAP: “This is probably the hardest thing I’ve ever done as a victim and survivor. It’s also the most necessary thing I can do for the people of California.”

Whatever happens, McNevin hopes these efforts will help expand the list. His abuser was named in multiple civil lawsuits, arrested, and convicted. Other survivors have never experienced this kind of validation.

“The Catholic faith calls for confession and penance,” McNevin says. “I expected to go into that church and into the chancery and to have the leaders of this church, who are the bishop and his senior priest and his staff, give me the full story—to do their penance.”

McNevin is no longer a practicing Catholic. But he’s still waiting for his diocese to do its penance—for the hundreds of likely survivors still waiting to see their abusers’ names on a list.

Survivors can find resources for SNAP and the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network here.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Second French priest commits suicide in church after abuse claims

A priest in central France accused of sexually assaulting a minor committed suicide in his church, Catholic authorities said Monday, the second French priest to take his life over abuse claims in a month.

Pierre-Yves Fumery, 38, hanged himself in his presbytery in the town of Gien in the Loire valley. His body was found on Saturday.

The public prosecutor for the area, Loic Abrial, told AFP he had been questioned last week by police about allegations of sexual assault involving a child under the age of 15.

Fumery had not been formally charged but was under investigation because of reports from the community about his behaviour, prosecutors said.

>Orleans bishop Jacques Blaquart, whose diocese includes Gien, called it a “moment of suffering and a tragic ordeal”.

Blaquart said some members of Fumery’s parish had brought attention to the priest’s “inappropriate behaviour” towards children aged 13, 14 and 15, including a girl “that he took in his arms and drove home several times.”

The bishop said the nature of the claims did not require the diocese to report the priest to the authorities and that he had told Fumery to “take a step back”, seek counselling and leave town for a little while.

The priest took his advice and returned to Gien after a short break but had not yet resumed his duties, Blaquart said.

He is the second priest in over a month to commit suicide in similar circumstances.

On September 19, Jean-Baptiste Sebe, also aged 38, hanged himself in his church in the northern city of Rouen after a woman accused him of sexually assaulting her adult daughter.

No formal complaint had been made at the time of his death.

The Catholic Church has been shaken by a string of paedophile scandals over the past 25 years.

The most senior French Catholic cleric to be caught up in scandal is Cardinal Philippe Barbarin, who is to go on trial in January for allegedly covering up for a priest accused of abusing boy scouts in the Lyon area in the 1980s.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

What it’s like to be a young Catholic in a new era of clergy sex abuse scandals

By Marisa Iati

In a yellow townhouse just steps from Georgetown University on a recent evening, members of the campus group Catholic Women at Georgetown talked about how the Virgin Mary strengthens them in hard times as they shared a dinner of Domino’s pizza.

In between swapping thoughts on homesickness and avoiding sin, the conversation turned to new allegations of sexual abuse by clergy in a church under siege.

The group’s president, Erica Lizza, asked the dozen students seated in a circle how they lean on Mary as the faith they’ve relied on for spiritual sustenance faces a crisis.

“I still do feel a level of disgust and betrayal by the Catholic hierarchy,” Lizza, a 21-year-old senior, said after the weekly dinner discussion. “As someone who cares a lot about her faith and who is very involved in a campus ministry organization, it’s something that there’s no escaping from.”

Similar conversations are playing out in dining halls and campus ministry centers across the country as college students wrestle with what it means to be Catholic at a time when they feel disappointed and angered by the church.

The church has seen multiple scandals in recent months: former U.S. cardinal Theodore McCarrick’s resignation amid accusations of abuse and a sweeping grand jury report out of Pennsylvania that implicated more than 300 priests in abusing about 1,000 children.

Then, Pope Francis accepted Cardinal Donald Wuerl’s resignation from his position as Washington’s archbishop after the Pennsylvania report described Wuerl as having a mixed record on responding to sexual abuse in his former diocese of Pittsburgh. Wuerl remains in charge of the archdiocesan administration until the pope names his successor. Clergy sex abuse scandals have also rocked Chile and Australia.

In an era when the church is frequently perceived as behind the times on matters of importance to them, some young Catholics have responded to the latest setbacks by pulling further away from the beleaguered institution, while others have drawn closer.

This generation of Catholic college students has grown up amid the stain of the sexual abuse crisis, which was first exposed by The Boston Globe in 2002 and has since implicated clergy around the world. Most can’t even remember a pre-scandal church.

At the same time, they and young people generally are a critical demographic for the future of Catholicism, which has an aging parishioner base and has struggled to attract and retain young people.

Catholicism has seen the largest decline in participation among major religious groups, according to a report in 2016 from the Public Religion Research Institute. Almost one-third of Americans said they were raised Catholic, but just 21 percent currently identify that way.

At a gathering this month of several hundred bishops to discuss the church’s ministry to young people, Pope Francis acknowledged those who have stood by the church, despite its failings.

“I thank them for having wagered that it is worth the effort to feel part of the Church or to enter into dialogue with her; worth the effort to have the Church as a mother, as a teacher, as a home, as a family, and, despite human weaknesses and difficulties, capable of radiating and conveying Christ’s timeless message,” Pope Francis said to open the synod, according to a copy of his remarks released by the Vatican.

Increasing disaffiliation with religion

Disillusionment over clergy sex abuse is not the only force pulling younger generations away from the Catholicism, particularly in the United States.

Increasingly over the past few decades, young adults have realized they can choose their own faith or combination of faiths, apart from those of their parents — or affiliate with none at all, said Theresa O’Keefe, a theology professor at Boston College who specializes in young adult faith. A growing distrust of institutional leadership of all kinds also means some students respond rather jadedly as more allegations of clergy abuse come to light, O’Keefe said.

William Dinges, a professor of religion and culture at Catholic University, said people who feel distant from the church are more likely to be affected by the abuse crisis than those who are devout. Many young adults are already frustrated with what they view as Catholicism’s less inclusive stances on topics such as same-sex marriage and gender equality, Dinges said.

“The young person has to have a good answer: ‘Why am I here?’ ” O’Keefe said. “The church, particularly the leadership, has to come up with a good answer. Why should people show up? Membership is not inevitable, and meaningful membership isn’t inevitable.”

Caroline Zonts, a 19-year-old sophomore at George Washington University, said she had started to feel put off by the Catholic Church long before the abuse crisis reemerged.

Raised “strictly Catholic,” she said the socially liberal political views she developed in high school made her feel less connected to her faith. When she arrived at college, Zonts said she stopped practicing Catholicism, although she still considers herself Catholic.

The recent abuse crisis has become another reason she doesn’t expect ever again to fully immerse herself in the church. It hurts her to think the priests she’s built relationships with may have committed abuse.

“They were mentors for me, they were role models, they were people I went to and talked to about my faith,” Zonts said. “That’s really hard — to know that hundreds of people like that have just abused their positions of power.”

Like Zonts, George Washington University junior Evelyn Arredondo Ramirez felt her more liberal political views were at odds with some parts of her Catholic faith. But even as a supporter of same-sex marriage and abortion rights, the 20-year-old still attended Mass most Sundays during her first two years of college.

Her perspective recently began to shift. Already annoyed with homilies that expressed the priests’ political opinions, her frustration was compounded by the Pennsylvania grand jury report and accusations that Pope Francis had knowingly shielded McCarrick from accountability.

Ramirez doesn’t go to Mass anymore and said she worries about her younger brother’s safety around priests in his home parish.

“I still have my Virgin (Mary) on my desk table, I still have the cross hanging in my room, and I will sometimes just pop into a church and just sit really with God,” Ramirez said. “But I’ve just developed my own idea of what it is to have that connection.”

Questions about the institution, not the faith

Many young Catholics who still consider themselves devout have responded not by turning away but by striving to force change from within the institution. For them, the current crisis is infuriating and heartbreaking, invigorating and empowering, all at the same time.

These young Catholics are among the more than 1,500 Georgetown students who have signed a petition calling on the university to rescind an honorary degree it awarded to McCarrick in 2004 and another it gave to Wuerl in 2014.

A Georgetown spokesman, in a statement, said the university was reviewing the honorary degrees in an effort “to address the deeply troubling revelations about Archbishop McCarrick and those contained in the Pennsylvania grand jury report.”

Among the students who feel unnerved by those revelations is Ana Ruiz, an 18-year-old member of Catholic Women at Georgetown, who said the scandal has made her doubt both her faith and her devotion to the church because the faith itself is closely tied to the institution. Catholics believe the church was founded by Jesus Christ.

“To just kind of see people who definitely do not embody those values that we hold so sacred really makes me question if the institution is working for the good of Christ and the good of the people,” Ruiz said as students cleaned up after the Georgetown discussion dinner.

Although still committed to Catholicism, Ruiz said she could imagine walking away from the institution if she no longer believed it cared about the best interests of lay people. Right now, however, she still feels like God is at the center of the church’s ministry.

“In that sense, I feel like I could never really break away,” Ruiz said. “But everything else that surrounds it, the humanly aspect of the Church, there could be potential for me to be like, ‘No, I can’t deal with that anymore.’ ”

Lizza’s childhood was steeped in Catholicism, with Sunday school and family Mass attendance and her mother reading to her from a children’s Bible. Even so, she was unsure how much she wanted to engage with her religion when she got to Georgetown because she was concerned about how her devout faith would mesh with that of her peers. Then a friend convinced her to join the Catholic women’s group and Lizza found a home.

Three years later, shocked and disgusted by the magnitude of the clergy sex abuse problem, Lizza said she started thinking maybe all bishops should resign. She fought to reconcile the idea of clergy who claim to stand for selfless love and a pursuit of justice with the knowledge that many had failed to live up to that promise.

Lizza said she never considered leaving the church. Rather, she felt stronger in her conviction that good people needed to stay involved in the institution to correct its course.

She still wants more lay people involved in the Church, despite how hard it was for her to attend Mass after the McCarrick allegations and the Pennsylvania report. She also wants people to be less skeptical of abuse victims.

“Covering it up sure as heck doesn’t work,” she said. “And the only way to really address it is to look at it square in the face and make some hard choices.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Oblate religious order covered up decades of sexual abuse of First Nations children, victims allege

Sexual abuse of Innu, Atikamekw children at hands of missionaries was rampant, Enquête finds

By

“He’d let us drive. He knew how to do everything. We were impressed to see a priest act that way,” recalls Jason Petiquay.

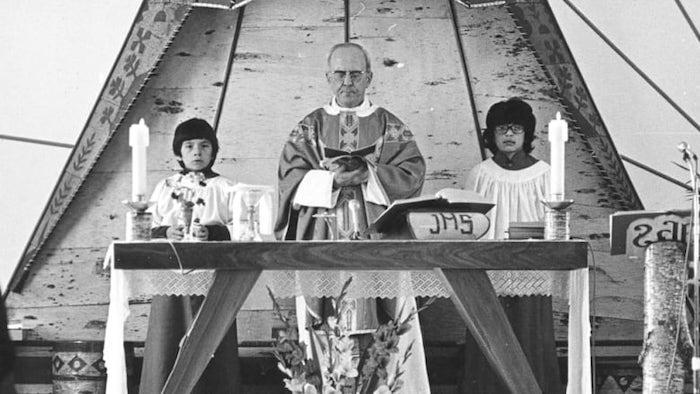

Petiquay was 11 when he was sexually abused by Raynald Couture, an Oblate missionary who worked in Wemotaci, Que., from 1981 to 1991.

The Atikamekw community 285 kilometres north of Trois-Rivières was one of many remote First Nations communities in Quebec where priests belonging to the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate (OMI) were spiritual leaders and authority figures for generations.

Petiquay described how Couture would lure young boys to his cabin by inviting them for a ride on his all-terrain vehicle or in his pick-up truck.

His story of abuse is one of dozens Atikamekw and Innu people in Quebec told Radio-Canada’s investigative program Enquête in a report set to air Thursday evening.

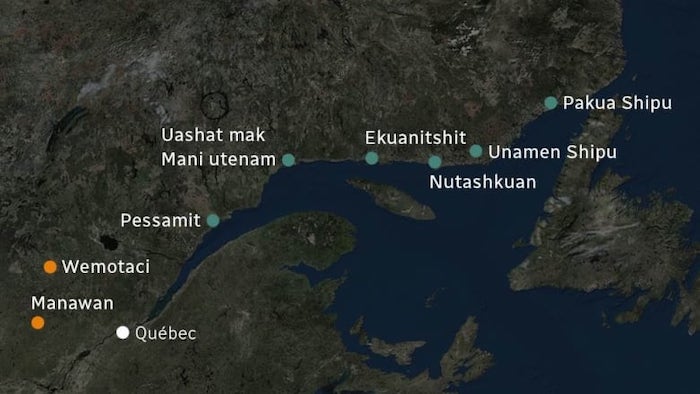

It paints of bleak portrait of widespread sexual abuse at the hands of at least 10 Oblate priests in eight different communities served by the missionary order, which began its evangelization work among Inuit and First Nations in Canada in 1841.

MMIWG shines light on decades-old secret

It has been almost a year since women from the isolated Innu communities of Unamen Shipu and Pakua Shipu, on Quebec’s Lower North Shore, described how they were sexually assaulted by an Oblate priest who worked in their territory for four decades, until his death in 1992.

One after another, alleged victims of the Belgian native, Father Alexis Joveneau, told the federal inquiry into missing and murdered Indigenous women (MMIWG) how the charismatic and much-admired priest had abused them as children.

“I could not talk about it,” Thérèse Lalo told commissioners. “He was like a god.”

In the wake of the testimony from Lalo and others, the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate issued an apology, setting up a hotline and offering psychological support to Joveneau’s alleged victims.

“We are absolutely devastated by these troubling testimonies,” the OMI’s Quebec office said in a March statement.

But the allegations in the Enquête report suggest the religious order’s superiors long knew about allegations against Joveneau.

Francis Mark, an Innu man from Unamen Shipu who said he was assaulted by Joveneau, said many years ago, he turned for help to the late Archbishop Peter Sutton, an Oblate who was made bishop of the Labrador City-Schefferville diocese in 1974.

“He let me down,” said Mark. “He didn’t guide me. Was there justice? No.”

Devout elders kept silence

In some instances which Enquête looked into, when Oblate superiors or church officials were told about the abuse, the priests were simply sent to neighbouring communities, where other Indigenous children were abused in turn.

In other cases, as in that of Father Raynald Couture in Wemotaci, deeply religious elders in the community insisted on silence.

“The mushums, the kookums [grandmothers and grandfathers], they asked him to stay in the community,” said Charles Coocoo, a Wemotaci man who once demanded that Couture leave.

Mary Coon, a social worker at the time, went straight to the religious order to ask them to intervene, but without an official police complaint, the Oblates refused.

“The boys wouldn’t file a complaint,” said Coon. “We wanted to get him out of here, but how could we? There was no complaint. We had nothing.”

In 1991, Couture was sent to France, where he remained until eight of his victims pressed charges. In 2004, he was sentenced to 15 months in jail, a punishment another victim, Alex Coocoo, called so light as to be “ridiculous.”

‘A sin to talk’

Claude Niquay said he was a seven-year-old altar boy when he alleges he was first molested by Father Clément Couture, another Oblate missionary who was posted in Manawan, an Atikamekw community southwest of Wemotaci, until 1996.

Niquay was forced to see his alleged abuser every day, when he delivered meals cooked by his grandmother to the priest.

When he tried to tell his grandmother about the assaults, he was punished.

“She’d tell me to go sit in a corner, that it was a sin to talk about those things,” he said.

Before Couture’s arrival, the community had been served by two other Oblate priests, Édouard Meilleur, and later, Jean-Marc Houle, whose alleged victims — elderly now — still recall their assaults vividly.

Antoine Quitish was just five when Meilleur allegedly stripped off his cloak and forced himself on him, “poking” Quitish’s chest with his penis.

“I’m happy that [the story] is out now,” said Quitish, now 75.

Other Atikamekw elders described Meilleur as an exhibitionist who would slip his hands under girls’ dresses during confession.

Enquête heard how Houle, who was posted in Manawan from 1953 to 1970, was drawn to pregnant women: he’s alleged to have spread holy oil over the stomachs, the breasts and the genitals of his victims, explaining he was warding off the devil in their unborn children.

The stories got out.

“I told the archdiocese, ‘If you don’t get that guy out of there, tomorrow morning it will be on the front page of the newspapers’,” recalls Huron-Wendat leader Max Gros-Louis, then the head of the Association of Indians of Quebec.

Houle was removed, said Gros-Louis — only to be sent to the Innu community of Pessamit, on Quebec’s North Shore.

Community warned of priest’s behaviours

Robert Dominique, then a band councillor in Pessamit, said his Atikamekw friends warned him about Houle, but the culture of the time ensured his silence.

“For elders, their faith is deeply rooted,” Dominique said. “Religion is sacred.”

Saying out loud that a priest was violating women and children was inconceivable, Gros-Louis agreed.

“You wouldn’t be allowed to go out anymore. You’d be banished, excommunicated,” he said.

There is no evidence Houle’s alleged assaults continued in Pessamit. However, people in that community recall abuse by three Oblate priests who preceded him.

Dominique’s sister, Rachelle, alleges she was first assaulted by Father Sylvio Lesage in the 1960s, and when Father Roméo Archambault replaced him in the 1970s, for her, things got worse.

He would take her into the church basement, she remembers.

“He was behind me, holding my little breasts,” she alleges, “and after I had to masturbate him in the dark.”

She described feeling “broken, vilified.”

Jean-Yves Rousselot also recounted being sexually assaulted by Archambault — alleged assaults that continued when that Oblate missionary was replaced by Father René Lapointe. The young altar boy told his grandfather what had happened and was beaten.

“I had to go to confession, to confess that I had committed blasphemy,” Rousselot said.

Lapointe was his confessor.

The priest would later be relocated to another Innu community, Nutashkuan, where he remained for 30 years, allegedly paying children to masturbate him.

In 2003, provincial police launched an investigation following a complaint, but charges were never laid.

Class action suit awaits Oblates

In the Innu community of Mani-Utenam, Gérard Michel recalls community elders sending him, along with another young man, to Baie-Comeau in 1970 to ask the archbishop to remove Father Omer Provencher, who is alleged to have been sexually assaulting girls in the community.

Nothing was done.

“Nothing, nothing, nothing,” said Michel, now an elder himself.

Provencher, who left the priesthood to live with an Innu woman years ago, told Enquête he will not answer any questions until he is formally charged with a crime.

Father René Lapointe, the priest who spent three decades in Nutashkuan, denies he ever sexually assaulted children.

Now at the Oblates’ retirement home in Richelieu, he told Enquête there is absolutely no truth in any of it.

“Nothing is true in that story. These are all inventions,” he said.

Raynald Couture, the Oblate priest who was found guilty of sexually assaulting children in Wemotaci, lives in the same retirement home.

He admits his past crimes.

“I drank like a bastard, and that’s when those things happened,” he told Enquête. He called his assaults “a weakness” and then a “game with the children,” and said he sought help from his superiors, asking to see the Oblates’ psychologist.

“They never even came,” he said.

Most of the priests accused of having assaulted so many Innu and Atikamekw people as children are dead now; Father Alexis Joveneau, who died in 1992, is buried in the cemetery in Unamen Shipu, where he spent so many years.

In late March, just days after the Oblates issued their apology and set up a hotline for Joveneau’s alleged victims, a class action suit was launched in Quebec for all victims of sexual assault at the hands of Oblate priests.

Lawyer Alain Arsenault says to date, 48 victims have come forward, alleging they were assaulted by 14 different Oblate missionaries.

With the court case pending, the head of the Oblates’ Quebec office, Father Superior Luc Tardif, turned down a request to be interviewed for this story.

Regardless of the results of that lawsuit, people in Unamen Shipu are asking that Joveneau’s remains, buried next to their Innu loved ones, be exhumed and taken away.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Feds Launch Sex Abuse Probe Of Pennsylvania’s Roman Catholic Church

By Bobby Allyn

The Department of Justice has launched an investigation of child sex abuse within Pennsylvania’s Roman Catholic Church, sending subpoenas to dioceses across the state seeking private files and records to explore the possibility that priests and bishops violated federal law in cases that go back decades, NPR has learned.

In what is thought to be the first-ever such inquiry into the church’s clergy sex-abuse scandal, authorities have issued subpoenas to look into possible violations of the federal Racketeering Influenced and Corrupt Organizations statute, also known as RICO, according to a person close to the investigation who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

The source did not elaborate on what other potential federal crimes could be part of the inquiry, which could take years and is now only in its early stages.

RICO has historically been used to dismantle organized-crime syndicates.

Officials at six of Pennsylvania’s eight dioceses — Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Allentown, Erie, Scranton and Harrisburg — have confirmed to NPR that they have recently received and are currently complying with federal subpoenas for information. The two remaining dioceses did not return requests for comment.

Supporters of those who have been victimized by church leaders applauded federal prosecutors for initiating a criminal investigation into one of the state’s most powerful institutions.

“There is a consensus rising, which is this just has to stop. And it won’t stop if prosecutors just sit on their hands,” said Marci Hamilton, University of Pennsylvania professor who also runs Child USA, a group that advocates for victims of child sex abuse. “The federal government has been silent on these issues to date, and it’s high time they got to work.”

The federal investigation follows a sweeping grand jury report released in August by the Pennsylvania Attorney General’s Office that found that more than 1,000 minors were abused by some 300 priests across Pennsylvania over a 70-year period.

A dozen other states have also opened investigations into clergy sex abuse.

Fallout from the Pennsylvania report has included Catholic schools that honored now-disgraced clergy being renamed and the archbishop of Washington, D.C., Cardinal Donald Wuerl, resigning after being accused of covering up sexual abuse during his time as bishop of Pittsburgh.

Numerous other church officials, the report found, participated in a systemic cover-up of the abuse that included shuffling priests around to other parishes and, in some cases, obstructing police investigations. However, because some of the allegations are decades old, many of the accused are now deceased.

Because of Pennsylvania’s statute of limitations, just two of the priests named in the report were charged as a result of the state-led investigation.

Carl Tobias, a law professor at the University of Richmond, says that the federal statute of limitations could allow more time to prosecute individuals who are now out of reach under state laws.

“This could bring the full force of the federal government to bear. It’s potentially enormous,” he said.

The subpoenas were first reported by The Associated Press, which said investigators sought to examine organizational charts, insurance coverage, clergy assignments and confidential documents stored in what has become known as the church’s “Secret Archives.”

U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania William McSwain authorized the subpoenas. A spokeswoman for McSwain declined to comment.

A Justice Department representative in Washington, D.C., would neither confirm nor deny the existence of the investigation.

Legal experts said accruing enough evidence to build a RICO case against the Roman Catholic Church — basically treating the influential institution as a crime syndicate — will be a burdensome task.

Child USA’s Hamilton, for one, said she thinks using federal RICO as a weapon against the church would be a stretch, since the 1970 law is not designed to deal with problems such as sex abuse and other personal injury cases. Instead, she said, most RICO cases involve financial crimes. “I hope that they can find a way to make it fit, but it will be challenging,” she said.

However, Hamilton said a federal statute called the Mann Act, which prohibits moving people across state lines for the purpose of illegal sex acts, could be a more promising legal avenue.

“As we know, there have been plenty of priests who took children across state lines,” she said.

Tobias, the law professor who specializes in federal courts, said whatever comes of the investigation, the issuing of the subpoenas has likely sent a jolt across the country. If the inquiry of the Pennsylvania church results in criminal charges, it could be used as a road map for federal prosecutors hoping to pursue abusers in other states.

“Pennsylvania might be the first state where the federal government does this,” Tobias said. “But then they build on the lessons they’ve learned there, as DOJ often does when they have a national issue, and go to the other states and use that template again.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!