By Robert Herguth

After Chicago Cardinal Blase Cupich caught heat in August for making remarks regarded as insensitive about the clergy sex abuse crisis, he took the unusual step of ordering Chicago-area Catholic priests to read a prepared statement during weekend masses defending him and insisting his comments had been twisted by the media.

With church officials again under fire — this time for a withering report from Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan that found the Catholic church in Illinois received hundreds more accusations of priests molesting kids than was previously known — Cupich has again sought to steer messaging from his priests on the topic.

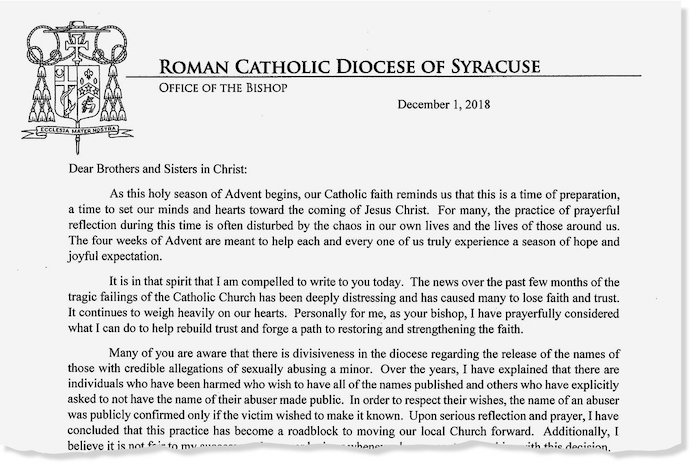

Just before Christmas, one of Cupich’s auxiliary bishops, Ronald Hicks, distributed a letter to priests suggesting ways to address the Madigan report and the overall sex abuse scandal during holiday masses. The letter suggests language the priests could use that acknowledges the church’s failures but also pushes back against some of Madigan’s findings.

The letter, obtained by the Chicago Sun-Times, also provides “talking points” priests can use when discussing the crisis with friends, family and parishioners over the holidays.

“As you know best the pastoral concerns and needs of your community, please feel free to share the following information in any way you deem appropriate,” Hicks wrote. “During this weekend, and perhaps during the Christmas liturgies, people will likely turn to you for guidance and understanding.

“We know that many parishioners will expect our parishes to address the attorney general report directly at mass. At the same time, we know many of you have already addressed this issue since this summer, and our Christmas masses will have many people, including many children, who may not be at mass that often.”

Like Cupich’s mandatory messaging from the pulpit in the summer, Hicks’ letter didn’t sit well with some clerics, even though it wasn’t as heavy handed. One Chicago-area priest who asked not to be named bristled over the content of the letter.

“I would say that I have never been sent so demeaning a note before,” the priest said. “If Hicks’ note was meant to be supportive, it wasn’t.”

Reached by the Sun-Times earlier this week, Hicks — who also serves as vicar general in Chicago, a top church post — deferred comment to Cupich’s press office, which didn’t immediately respond.

Madigan’s report, which is considered preliminary, noted that Illinois dioceses publicly identified 185 clergy with credible allegations of child abuse over decades. Her investigators found another 500 priests faced accusations that were not publicized, though it’s unclear how many of them were valid, and which dioceses had the most problems.

Church officials said all credible allegations were made public, but Madigan said many alleged abuse cases that the church didn’t consider credible weren’t thoroughly investigated by the dioceses.

It’s unclear how many priests if any used Hicks’ suggested language in masses or conversations with parishioners or others.

While providing a “sample text for upcoming liturgies” that could be used “perhaps as an introduction to the liturgy, during announcement time or within the homily,” Hicks’ letter offered the following wording for priests to relay to congregants:

“We know these are difficult times for our church, and you probably saw the headlines in the last few days regarding the attorney general’s report in Illinois. The church everywhere and in the Archdiocese of Chicago recognizes and mourns the grave damage done to many people harmed by clergy sexual abuse and regrets the failures to respond.”

The letter notes that the report covers the state’s six Catholic dioceses — which each have their own geographic boundaries, bishops and bureaucracy — and not just the Chicago archdiocese, which is overseen by Cupich and covers Cook and Lake counties.

“Contrary to what has been reported, the archdiocese presented clear evidence to the attorney general that it has reported all allegations to law enforcement and has reached out to all those bringing allegations and offered pastoral care,” the letter states.

Hicks wrote in his letter to priests that “I also recommend reading and sharing, as appropriate” a Dec. 20 Chicago Tribune editorial. In part, that editorial said “while Madigan’s document includes strong accusations, it doesn’t offer a clue about which church officials allegedly fell short in which diocese, past or present. We hope the final report, whenever it emerges, will be structured to make it more useful to citizens and civil authorities going forward.”

Hicks’ letter also offers possible prayers that could be read from the altar at mass.

“For parents, guardians, mentors, teachers, coaches and all who work with children and young people, that they may look after them with the watchful eye of the shepherd, we pray to the Lord,” one reads.

Among the talking points included in the letter, priests can let people know that “the archdiocese has been working to develop strong policies and procedures to heal victims and prevent abuse since 1992.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!