It was a list Charles L. Bailey Jr. had wanted to see for years: the names of the priests in the Roman Catholic Diocese of Syracuse who had been credibly accused of sexual abuse.

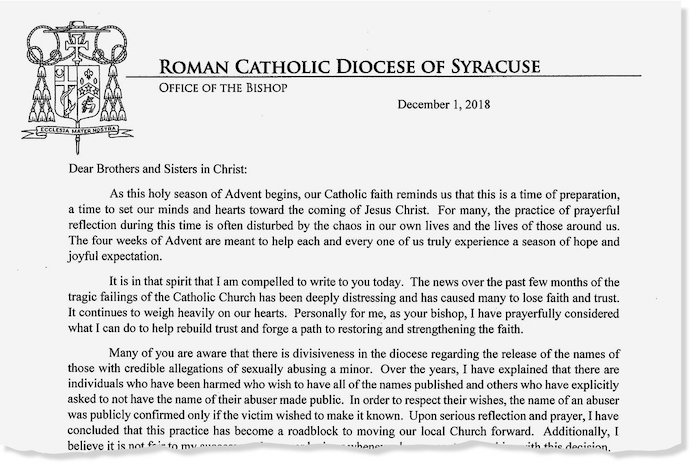

Mr. Bailey, 67, a longtime local advocate for survivors of abuse by priests, had heard excuses for why such a list was impossible to release. The last bishop said naming accused priests would be a violation of the Ten Commandments. The current bishop said he would not disclose the names, citing the request of unnamed victims.

But then on Dec. 3, Mr. Bailey got a call from a local reporter. It was up, on the diocesan website. Fifty-seven priests. None were still in ministry and most were deceased, including, there on Page 4, the priest who had repeatedly raped Mr. Bailey when he was not yet a teenager.

As the Catholic Church faces a wave of federal and state attorney general investigations into its handling of sex abuse, bishops around the country have struggled with how to react. Some have locked down defensively. Others are waiting on guidance from the Vatican, which instructed American bishops last month to wait on taking any collective action until the new year.

But dozens of bishops have decided to take action by releasing lists of the priests in their dioceses who were credibly accused of abuse. And they are being released at an unprecedented pace.

The disclosures have trickled out week by week — 10 names in Gaylord, Mich.; 28 in Las Cruces, N.M.; 28 in Ogdensburg, N.Y.; 15 in Atlanta; 34 in San Bernardino, Calif., among many others. All 15 dioceses in Texas have agreed to release lists. Last week, the leaders of two major Jesuit provinces, covering nearly half of the states, released the names of more than 150 members of the order “with credible allegations of sexual abuse of a minor.”

“We’ve never seen this kind of outpouring before,” said Terry McKiernan, co-director and president of BishopAccountability.org, which tracks clergy sex abuse cases.

By his count, at least 35 dioceses have released lists or updates of previous lists since the beginning of August. That nearly doubles the number that had ever been released before, since the first one in 2002 by the Diocese of Tucson.

“It’s a dramatic change in how bishops are approaching this,” Mr. McKiernan said.

Many of the priests named on the lists are dead, but not all. Many had already been known as abusers, but scores of names are new, even to activists who have been closely following the church abuse scandals for years. Among the known allegations, many of the cases date back generations.

But few of the lists provide details about the allegations themselves, including when they occurred or how many victims were affected.

Some victims, as they comb through the lists, say there are names missing. Others see reason for distrust in the fact that the church had names to release at all, nearly two decades after claiming the sexual abuse scandals introduced a new era of transparency.

The lists are coming in the wake of an explosive grand jury report released in August by the Pennsylvania attorney general’s office, detailing at grim length the abuse of over 1,000 people by hundreds of priests. Investigations have followed in more than a dozen states.

“Names coming out this way,” Mr. McKiernan said of the voluntary releases, “is really different from the way they came out in the grand jury report.”

The scope of the federal investigation remains unclear. Last month, William M. McSwain, the United States attorney for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, sent a request to every Roman Catholic diocese in the United States not to destroy documents related to the handling of child sexual abuse.

Still, if releasing the lists was meant to defuse the anger of the church’s critics, there is little evidence it has done that.

Sign Up for On Politics With Lisa Lerer

A spotlight on the people reshaping our politics. A conversation with voters across the country. And a guiding hand through the endless news cycle, telling you what you really need to know.

In Syracuse, Mr. Bailey said that he had already received calls from victims who said their abusers were not on the list. The name of the priest who had raped Mr. Bailey was listed in a section for clergy who “were deceased at the time of the reporting of the allegation,” a claim he said was contradicted by some of the priest’s abuse victims.

“There’s no credibility,” said Mr. Bailey, head of the local chapter of S.N.A.P., the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests. “I thought it was going to be more gobbledygook and that’s just what it is.”

The Diocese of Syracuse said it had heard from people who were unhappy with the list’s release and others who were grateful.

“It is not surprising that there are mixed reactions to the list as it was and continues to be a divisive issue,” said Danielle Cummings, the chancellor and director of communications for the Syracuse diocese. She said the list was put together from a comprehensive review of allegations of abuse going back 70 years, but added: “If there is a name that individuals believe should be on the list, they can bring it forward to the diocese or the District Attorney.”

With no central reporting system and given the movement of priests around dioceses, it is hard to judge how comprehensive the lists may be, even by comparing them with previously disclosed numbers.

In Buffalo, a former assistant to the local bishop came forward to say that the list released by the diocese, with 42 names, was far shorter than the dioceses’ internal list, which had more than 100 names. Sexual abuse victims in Rockford, Ill., said the names of their abusers were nowhere on the list released there.

Among a laity distrustful of the church’s handling of sex abuse, there is a widespread sentiment that the only way to get the truth is through the subpoena power of law enforcement.

“The civil court system, that’s the new way the Holy Spirit moves,” said Patrick Wall, a former priest and canon lawyer who now works on behalf of abuse victims.

Advocacy groups suggest that bishops could invite the authorities to pore through all of a diocese’s files. Or the authorities could come in uninvited, as was the case when dozens of federal and local agents conducted a surprise search of the offices of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston last month.

Yet civil authorities have limits, too, as was made clear in a recent decision by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. In a Dec. 3 opinion, the court agreed with a group of unnamed priests who argued that the grand jury report did not allow them their right of due process to submit evidence and arguments in their defense. Their names remain redacted in the report.

The bishops who are trying to compile their own lists are wrestling with some of the same issues.

At a meeting of bishops in Baltimore in November, Bishop Thomas Paprocki, of Springfield, Ill., told his fellow bishops it was not as simple as deciding that an allegation was credible, or not credible. He asked: What if a priest was accused 20 years ago, but the diocesan review board that was supposed to judge the case never came to a conclusion?

“If it was inconclusive 20 years ago, it’s still inconclusive,” he said, “and I hesitate to come down on one side of that.”

In an interview this week, Bishop Christopher Coyne of the Diocese of Burlington, Vt., said he had long considered the downsides of lists like these greater than their upsides. No one was ever satisfied with them.

“If you had asked me a year ago if I were going to publish a list, I would have said no,” Bishop Coyne said.

But the times have changed. In September, a joint state and local law enforcement task force began looking at allegations of severe abuse decades ago at a Catholic-run orphanage in the Burlington diocese. The diocese says it is cooperating; officials are in the offices every week.

Since early November, a board of lay people, chaired by a non-Catholic, has been coming to the diocesan offices to examine files relating to accused priests. The board is expected to produce a list of names by the end of the year.

The mistrust underlying all this was earned, Bishop Coyne said. The bishops had proven over the last two decades that they had not been able to police themselves. But given the current atmosphere, self-policing might not be an option any more.

“Now I have a reason,” Bishop Coyne said of pushing for the publication of a list. “The list is going to get published anyway.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!