Rome vs. the Sisters

Commentators offer a range of explanations for last week’s Vatican “assessment” charging a group that includes the largest number of US Catholic sisters, the Leadership Conference of Women Religious (LCWR) with “serious doctrinal problems” and “radical feminism.”

One frequent explanation is that the report was issued in retaliation for support given the 2009 Affordable Care Act (ACA) by Network, a Catholic social justice lobby with close ties to the LCWR. For example, in a BBC News interview several days after the release of the assessment, Sister Simone Campbell, Network’s executive director, acknowledged “a strong connection” between Network’s challenge to the US bishops over the ACA and the Vatican accusations.

One frequent explanation is that the report was issued in retaliation for support given the 2009 Affordable Care Act (ACA) by Network, a Catholic social justice lobby with close ties to the LCWR. For example, in a BBC News interview several days after the release of the assessment, Sister Simone Campbell, Network’s executive director, acknowledged “a strong connection” between Network’s challenge to the US bishops over the ACA and the Vatican accusations.

No doubt there is some truth to this analysis. But it’s worth noting that the Vatican launched the investigation that culminated in this document in January 2009, more than a year before Congress passed the ACA. Given the speed with which Rome does things, it’s more than likely that while the sisters’ support for the ACA contributed to the harshness of the statement, it by no means caused it. Indeed, Pope John Paul II mandated a previous investigation of US religious in 1983, though the outcome of that process was less brutal than the current one has proven to be.

In point of fact, throughout the history of the Church, bishops and popes have struggled mightily to keep committed celibate Catholic women under control. Already in the early Christian centuries male church leaders forced virgins to describe themselves as “brides of Christ” rather than use the male martial imagery they had come to use during the Roman persecutions. The early equality between male and female desert monastics was likewise undercut when eighth century bishops began taking control of women’s monasteries and ordained monks to the priesthood for the first time (but not nuns, of course.) And as, throughout the following centuries, groups of dedicated Christian women came together—canonesses, Beguines, beatas, recluses—popes, bishops, and male theologians went to great lengths to rein them in.

In the 12th century, Aelred of Rievaulx forbade women recluses to so much as talk alone with their confessors; Gregory IX imposed cloister on all Franciscan sisters except those in the house led by their foundress, Clare of Assisi; and in 1917, after a century marked by the foundation of innumerable active (that is, non-cloistered) congregations of sisters dedicated to serving the needs of the sick and the poor, the new Vatican Code of Canon Law cloistered them all, imposing rigid rules that undercut their ministries.

As the century moved on, however, relations between the Vatican and the sisters seemed to improve. In its effort to respond to the horrors of the twentieth century, the Vatican ordered the sisters to become better educated, to update their rules and habits, and to begin meeting together for the sake of greater effectiveness.

Already in 1929 Pope Pius XI had stressed the need for better prepared Catholic school teachers; in 1950, Pius XII called a meeting of the heads of all religious orders for the purpose of further advancing their collaboration; and in 1952 he called a meeting of women’s superiors, during which he urged the sisters to update and educate themselves for the purpose of attaining attain equal footing with their secular counterparts.

The Vatican also called for the formation of the US Conference of Major Superiors of Women, the group that eventually morphed into the currently-maligned LCWR. Ironically, the American women’s congregations at the time felt no need for the Conference, but organized it out of obedience to the Pope. Finally, the Second Vatican Council called the sisters to renew their congregations, return to the charism of their founders, and revise their constitutions, a call Pope Paul VI seconded. The sisters embraced Vatican II renewal immediately, with all their hearts, more so than any other group in the church.

So how, you may wonder, did the sisters and the Vatican get into the current conundrum? In much the same way that the rest of the Catholic Church did in the decades after Vatican II.

Conservative commentators argue that the sisters misinterpreted the teachings of Vatican II, or didn’t study them at all, and abandoned the way of life to which they were vowed. More illuminating, I believe is a comment made in 2005 by Sister Mary Daniel Turner, an LCWR executive director who, in the 1970s, led the organization through some of its most significant transformations: “Each time the church takes a step forward,” she said, “it takes a step back.” At Vatican II, the church called its members to respond to the “signs of the times,” to recognize “the universal call to holiness” that made clergy, religious and laypeople equal, to respond to the “joys and hopes, the griefs and anxieties” of modern men and women.

But when the “People of God” began to do this, the Vatican and the bishops realized with a shock what it actually meant, and they didn’t like it.

In point of fact, according to papers released in 2011 by the moral theologian Germaine Grisez, papal buyers’ remorse had become evident even before the closing of the Council, when Pope Paul VI made clear that he would not reverse the church’s earlier condemnation of artificial contraceptives under any circumstances. And in 1968 he was true to that promise, absolutely forbidding, in his encyclical Humanae Vitae, the use of artificial contraceptives. In so doing the pope overrode the recommendations of the birth control commission formed during Vatican II, a commission that included married lay people. So much for the equality that came with the “universal call to holiness.”

US sisters themselves began slamming into the buyers’ remorse of the institutional church around the same time. Already in 1967, the rollback of the renewal the sisters had undertaken with such commitment began to come into focus. When the cardinal archbishop of Los Angeles forbade the Immaculate Heart Sisters there from implementing the changes agreed upon at their renewal chapter, including modernizing their habit and educating their young sisters before sending them out to teach, the Vatican backed the cardinal, although these were changes the Vatican itself had called for. Ultimately, a majority of IHMs abandoned their status as Catholic sisters under canon law.

When LCWR members proposed a motion protesting the treatment accorded the IHMs, the Vatican representative at their meeting prevented the motion from coming to a vote. In the years that followed, the LCWR protested to Rome repeatedly what appeared to them unjustifiable intrusions by the Vatican and the bishops in decisions over which the Council had given them discretion.

I could go on but you get the idea. The recent investigation of the LCWR and accusations of doctrinal infidelity and radical feminism against the group are one more sad chapter in the long history of popes and bishops attempting to bring Catholic sisters to heel.

There is one significant difference, however. In part because of the Vatican’s own demand that they become so, the sisters currently under attack are the most highly educated women in the history of the church.

And because of the sisters’ hard, able, for the most part financially uncompensated work, Catholic women in the US today are also vastly more educated, competent, and professional than Catholic women of any previous generations. Think here, if you will, of Nancy Pelosi, recent occupant of the highest position of power a woman has held in the history of the US government. Think of Kathleen Sebelius. Think, for that matter, of me. We Catholic women understand the enormous debt we owe our sisters, and we are not pleased to have their faith denigrated in such a vile fashion even as they move into old age.

To paraphrase Sister Simone Campbell, I don’t think the boys have any idea what they’re in for.

Complete Article HERE!

Bishops Play Church Queens as Pawns

COMMENTARY

IT is an astonishing thing that historians will look back and puzzle over, that in the 21st century, American women were such hunted creatures.

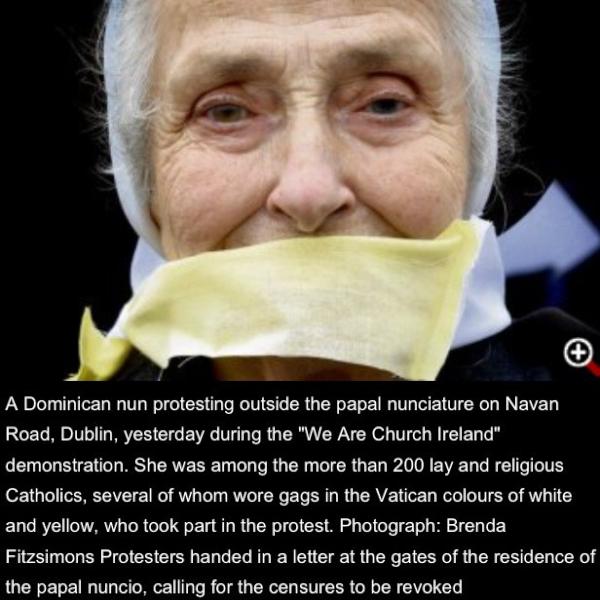

Even as Republicans try to wrestle women into chastity belts, the Vatican is trying to muzzle American nuns.

Even as Republicans try to wrestle women into chastity belts, the Vatican is trying to muzzle American nuns.

Who thinks it’s cool to bully nuns? While continuing to heal and educate, the community of sisters is aging and dying out because few younger women are willing to make such sacrifices for a church determined to bring women to heel.

Yet the nuns must be yanked into line by the crepuscular, medieval men who run the Catholic Church.

“It’s not terribly unlike the days of yore when they singled out people in the rough days of the Inquisition,” said Kenneth Briggs, the author of “Double Crossed: Uncovering the Catholic Church’s Betrayal of American Nuns.”

How can the church hierarchy be more offended by the nuns’ impassioned advocacy for the poor than by priests’ sordid pedophilia?

How do you take spiritual direction from a church that seems to be losing its soul?

It has become a habit for the church to go after women. A Worcester, Mass., bishop successfully fought to get a commencement speech invitation taken away from Vicki Kennedy, widow of Teddy Kennedy, because of her positions on some social issues. And an Indiana woman named Emily Herx has filed a lawsuit saying she was fired from her job teaching in a Catholic school and denounced as a “grave, immoral sinner” by the parish pastor after she used fertility treatments to try to get pregnant with her husband.

Cardinal Timothy Dolan of New York recently told The Wall Street Journal that only “a tiny minority” of priests were tainted by the sex abuse scandal. But it’s a global shame spiral. The church leadership never recoiled in horror from pedophilia, yet it recoils in horror from outspoken nuns.

In Philadelphia, Msgr. William Lynn, 61, is the first church supervisor to go on trial for child endangerment. He is fighting charges that he may have covered up for 20 priests accused of sexual abuse and left in the ministry, often transferred to unwitting parishes.

Somehow the Philadelphia church leaders decided that the Rev. Thomas Smith was not sexually motivated when he made boys strip and be whipped playing Christ in a Passion play. Somehow they decided an altar boy who said he was raped by two priests and his fifth-grade teacher was not the one in need of protection.

Instead of looking deep into its own heart and soul, the church is going after the women who are the heart and soul of parishes, schools and hospitals.

The stunned sisters are debating how to respond after the Vatican’s scorching reprimand to the Leadership Conference of Women Religious, the main association of American Catholic nuns. The bishops were obviously peeved that some nuns had the temerity to speak out in support of President Obama’s health care plan, including his compromise on contraception for religious hospitals.

The Vatican accused the nuns of pushing “radical feminist themes,” and said they were not vocal enough in parroting church policy against the ordination of women as priests and against abortion, contraception and homosexual relationships.

In a blatant “Shut up and sit down, sisters” moment, the Vatican’s doctrinal office, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, noted, “Occasional public statements by the L.C.W.R. that disagree with or challenge positions taken by the bishops, who are the church’s authentic teachers of faith and morals, are not compatible with its purpose.”

Pope Benedict, who became known as “God’s Rottweiler” when he was the cardinal conducting the office’s loyalty tests, assigned Archbishop J. Peter Sartain of Seattle to crack down on the climate of “corporate dissent” among the poor nuns.

When the nuns push for social justice, they’re put into stocks. Yet Archbishop Sartain has led a campaign in Washington to reverse the state’s newly enacted law allowing same-sex marriage, and he’s a church hero.

Sister Simone Campbell, executive director of Network, a Catholic lobbying group slapped in the Vatican report, said it scares the church hierarchy to have “educated women form thoughtful opinions and engage in dialogue.”

She told NPR that it was ironic that church leaders were mad at sisters over contraception when the nuns had committed to a celibate life with no families or babies. Given the damage done by the pedophilia scandals, she said, “the church’s obsession, at times, with the sexual relationships is a serious problem.”

Asked by The Journal if the church had a hard time convincing the flock to follow its strict teachings on sexuality, Cardinal Dolan laughed: “Do we ever!”

Church leaders behave like adolescent boys, blinded by sex. That’s the problem with inquisitors and censors: They become fascinated by what they deplore.

The pope needs what the rest of us got from nuns: a good rap across the knuckles.

Complete Article HERE!

Holy Wisdom Monastery provides church services for disaffected local Catholics

Alice Jenson’s faith took an irreversible turn six years ago.

It was Nov. 5, 2006, and she was contributing to Mass at St. Joseph’s Catholic Church in Madison as a lay person, reading Bible passages from the lectern.

The same day, Madison Bishop Robert Morlino required all priests to play a recorded message from him explaining his position on three issues state residents would vote on that week, including a ban on same-sex marriage, which he supported.

When the priest hit “play,” Jenson walked out.

“It was the first time I’d ever outwardly gone against what I was raised to follow,” said Jenson, 67.

She found a new religious home at Holy Wisdom Monastery, a former Roman Catholic monastery in the town of Westport, just outside Madison. Its Sunday service, offered by the sisters who live there, retains many elements of a traditional Catholic Mass but diverges in sometimes startling ways.

Women can lead the service and preach the sermon. Gay relationships are warmly embraced. All parishioners, not just Catholics, can consume the communion wine and bread because the service is ecumenical, meaning welcoming of all Christian traditions.

It’s an alternate universe of sorts — what some think a Catholic Mass might look like today if the liberal spirit of Vatican II in the 1960s had taken root and flowered.

“We’re doing what the hierarchical church was afraid to complete,” said Jim Green, a longtime Holy Wisdom parishioner who is gay and describes himself as “a Catholic in exile.”

The service, called Sunday Assembly, is attended by people from many denominational backgrounds but has become especially popular with Catholics displeased with Morlino or church doctrine in general. Membership doubled in five years to 335, and parishioners estimate a majority are Catholics who left their regular parishes.

Detractors say the parishioners strayed too far from Catholicism to warrant the label.

Approach evolves

Though many self-described Catholics attend Holy Wisdom, it’s no longer an official Catholic Mass.

A little history: In the 1950s, a group of Benedictine nuns opened a high school at the site for girls in the Madison Catholic Diocese. Benedictines belong to a monastic religious order regulated by the canon law of the Catholic Church. Masses at the site were led by Catholic priests, often provided by the diocese.

In 1966, the nuns closed the school and turned the buildings into a Christian retreat center. The sisters, spurred by the Benedictine tradition of hospitality, gradually made the service more inclusive to all Christians. Lay people, especially women, took on greater roles.

In 2000, the Benedictine sisters went a step further, welcoming a Protestant woman to live with them. “When we chose to open our community to Protestant women, it meant other doors closed,” said Sister Mary David Walgenbach, the monastery’s head.

The sisters sought independence from the Catholic Church, and the Vatican granted it in 2006. Consequently, they no longer are tied to the local diocese. They remain affiliated with a Benedictine federation, but they have a special status, not a full membership, because of their ecumenism.

Bishop’s request

When the sisters disassociated from Rome, Bishop Morlino asked them to no longer celebrate Mass at the site so as not to cause confusion, said Brent King, a diocesan spokesman.

“Many people had visited (the monastery) over the years, and the bishop felt it would take time for people to understand that it was no longer a Roman Catholic institution,” King said, adding the bishop “was in no way unfriendly toward their desire to start a non-Catholic ecumenical community.”

The sisters understood the bishop’s position and stopped calling the service a Catholic Mass in 2006, Walgenbach said. Priests ceased to lead the service.

Today, the sisters describe the Sunday Assembly as being “for the celebration of Eucharist,” a term most commonly used to refer to Catholic communion. However, Walgenbach said some Protestant churches also use it. To many people, the service still has the essence of a Catholic Mass.

“You wouldn’t know it wasn’t a Catholic church, except for the person officiating,” said parishioner Pat Hobbins-Kemps, 64. A lifelong Catholic, she said she left her regular parish partly out of a lack of opportunities for women to lead.

Finding a home

Trisha Day, 66, said she came to Holy Wisdom after growing tired of sermons that focused on politically charged issues such as abortion and homosexuality while saying little about social justice and the poor.

Jeanne Marquis, 68, found Holy Wisdom after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. “I needed someone to talk about forgiveness instead of retaliation,” she said. “I needed a place where I was encouraged to ask questions.”

Ann Baltes, 44, a lifelong Catholic, said she sought a place where she and her husband, Bill Rosholt, a Lutheran, could participate in communion together.

Are these parishioners still Catholic? The answers vary.

Jenson says she’s not. “Too much divides us.”

Day calls herself “a transitional Catholic,” unsure where she’ll end up. Green said his Catholic identity can’t be taken from him. “The church is the people of God, not the institution,” he said.

Joanne Kollasch, one of the three Benedictine sisters who live at the monastery, said she “is a Catholic and will remain a Catholic,” adding, “I don’t like to be thought of as less Catholic because I’m ecumenical.”

Said Walgenbach: “The Catholic spirituality is bigger than the Roman Catholic Church.”

Both sisters said they respect the Catholic Church and Morlino and don’t seek controversy.

Detractors

Syte Reitz, a member of Madison’s Cathedral Parish who blogs about Catholic issues, said disaffected Catholics are free to start their own churches, but they shouldn’t confuse people by suggesting they still are faithful Catholics.

“Does it matter whether they are errant Catholics or not Catholics?” asks Reitz. “No matter what we label them, the laws of right and wrong and of morality still stand, and they and others will suffer from the mistakes that they make.”

Reitz said because a male priest is not presiding over the Eucharist, the bread is not being turned into the body of Christ, thus depriving attendees of the Catholic Church’s central sacrament.

King, the diocesan spokesman, said for Catholics to fulfill their obligation to attend Mass on Sundays, they must attend a Catholic Mass validly offered by an ordained Catholic priest.

Does the Holy Wisdom service qualify?

“In charity, we must respond that it does not,” he said.

Complete Article HERE!

Jacqueline G. Wexler, Ex-Nun Who Took On Church, Dies at 85

Jacqueline G. Wexler, a former Roman Catholic nun who fought the Vatican’s authority and won, then found herself on the other side of the barricades when she became president of Hunter College in 1970, facing student demonstrators storming her office, died on Thursday in Orlando, Fla. She was 85.

Enlarge This Image

Her death was confirmed by her daughter, Wendy Wexler Branton.

While still a nun and battling the church on many issues, Ms. Wexler drew nationwide attention as a bellwether of the liberal reforms of the Second Vatican Council. She fought successfully against church control of Webster College, the small Catholic women’s college near St. Louis that she headed in the 1960s. She advocated greater participation by women in church leadership and criticized the church’s ban on birth control.

While still a nun and battling the church on many issues, Ms. Wexler drew nationwide attention as a bellwether of the liberal reforms of the Second Vatican Council. She fought successfully against church control of Webster College, the small Catholic women’s college near St. Louis that she headed in the 1960s. She advocated greater participation by women in church leadership and criticized the church’s ban on birth control.

Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen, the Catholic televangelist, referred to her as a “Benedict Arnold” in 1967, the year she won autonomy for Webster and simultaneously renounced her vows. Dick Cavett had her as a guest on his late-night TV talk show.

Ms. Wexler’s appointment in 1970 as president of Hunter, one of 11 colleges in the City University of New York system, coincided with a turbulent year in its history. Students, roiled by a combination of antiwar politics and local tensions caused by rising fees and a new university-wide open admissions policy, held demonstrations that shut down the campus repeatedly that spring.

Protesters blocked building entrances and elevators, forcing others to use emergency doors and stairways. Ms. Wexler, refusing at first to call the police, waded into angry crowds to talk, only to be shouted down. Barricaded in her office several times, she finally called the police.

A reporter for The New York Times was in the president’s office one afternoon that April when the phones rang, bringing news that students had blocked elevators and entrances for the second time that month.

“Here we go again,” Ms. Wexler said.

Outside her window, protesters chanted in rhyme, accusing her of colluding with “pigs,” the epithet they used for the police.

Ms. Wexler said that if anything had prepared her for the turmoil, it was having been a lightning rod for condemnation by conservatives in the church.

“Zealotry is the enemy,” she said, adding: “The far right called you every name, from daughter to Beelzebub on, and you learned to take it.”

She was born Jean Grennan on Aug. 2, 1926, the youngest of four children of Edward and Florence Grennan, who owned a small farm in Sterling, Ill. She later took the name Jacqueline in honor of an older brother, Jack, who died of a brain tumor at 21.

After graduating from Webster College, she entered the order of the Sisters of Loretto in 1949, and taught high school math and English in St. Louis and El Paso, Tex. She received her master’s in English from the University of Notre Dame in 1957, and returned to Webster in 1959 as an instructor and administrator.

Sister J., as she was known, was named president of Webster in 1965. She began initiatives aimed at raising educational standards and halting declining enrollment, then common among Catholic women’s colleges.

Sister J. made institutional separation from the church her first priority. “The very nature of higher education is opposed to juridical control by the church,” she said at the time.

She also led the transition to co-education, built new facilities, and started a social-justice program that sent students to work in the poorest neighborhoods of St. Louis, attracting the attention of the Kennedy administration.

She was appointed to the president’s advisory panel on research and development in education and to the original steering committee that developed Project Head Start, the federal program for low-income children.

After several years of well-publicized jousting with Sister J., the Vatican, in 1967, granted the Sisters of Loretto permission to put Webster under the control of an independent, secular board of trustees. It was one of the first Catholic colleges to cut its ties to the church. Asked for his reaction, Archbishop Sheen replied to a reporter: “No comment. I am more interested in Nathan Hales than Benedict Arnolds.”

In 1969, the former Sister Jacqueline married Paul Wexler, a record company executive, and adopted his two children, Wayne and Wendy. Besides Ms. Wexler Branton, Ms. Wexler is survived by her husband and son, as well as four grandchildren, two great-grandchildren and two sisters.

Ms. Wexler was known as a calming presence at Hunter. She led it through the rocky early 1970s and helped make it the city university’s premier center for health care education. Before stepping down in 1979, she brought Bellevue Hospital’s nursing school into the college, expanded health care training, raised money to start a gerontology program in the school of social work and inaugurated a women’s studies program.

From 1982 until 1990, she was president of the National Conference of Christians and Jews.

After receiving an honorary degree from her alma mater, now Webster University, in 2007, Ms. Wexler, then 81, was given a tour of the campus by the president accompanied by a reporter for The St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Many buildings had been added since she left. She was eager to see them all, the newspaper said, and seemed to grow impatient when the elevator in one building was slow to arrive.

Whether out of eagerness or habit forged in the crucible of 1970, Ms. Wexler proceeded to the stairs.

“Let’s walk,” she said. “I wore comfortable shoes.”

Complete Article HERE!