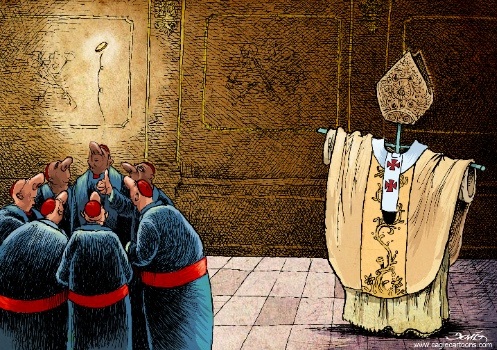

As a conclave gathers to elect a pope, many in the Catholic church want change

WANTED: man of God; good at languages; preferably under 75; extensive pastoral experience; no record of covering up clerical sex abuse, deeply spiritual and, mentally, tough as old boots. It is a lot to ask, but that is the emerging profile of the man many of his fellow-cardinals would like to see replace Benedict XVI as the next pope.

On March 4th the princes of the church began a series of preliminary “general congregations”, the first step to electing a pontiff. They have much to discuss. After four sessions, they had still not—as expected—fixed a date for the Conclave, the electoral college, made up of cardinals below the age of 80, which will actually choose the next pope.

The papal spokesman, Father Federico Lombardi, said the members of the general congregation, who include older cardinals, are not “hurrying things”. By March 6th, when they adjourned, the assembly had heard 51 speeches. As Father Lombardi tactfully put it, they spoke “freely and with rather effective colour”. That is code for candour—even bluntness. Indeed, given the crises the church faces, delicacy might seem remiss.

The procedure is usually to identify the main threats facing the church and then find the cardinal best able to deal with them. Of the subjects cited by Father Lombardi, half concerned the Vatican itself. Deeper questions include the loss of religious faith in Europe; the challenge from evangelical Protestantism in Latin America; persecution of Christians in the Middle East and clerical sex abuse. But none is as pressing as the turmoil in the Roman Curia, the church’s central administration.

Benedict, intellectually fearless yet personally timid, was unable to keep order. Many in Rome believe that was the true reason for his departure. The Curia has become a battleground. Prelates loyal to the secretary of state, Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone, who in many cases were appointed by him or come from his native region of Piedmont, are at furious odds with papal diplomats who resented the appointment of a secretary of state with no knowledge of their business. Other feuds abound too. The leaking of documents by the pope’s butler, Paolo Gabriele, though apparently motivated by genuine dismay at decisions taken in the Vatican, was entwined with this venomous plotting and squabbling.

Following the will of God

The findings of an investigative panel of three cardinals will cast a long shadow over the conclave. Last month an Italian newspaper wrote of a ring of gay prelates, some being blackmailed by outsiders. In the first general congregation, three cardinals—reportedly all Europeans—demanded (in vain) access to the findings. If the report will indeed be kept secret until it is handed to the new pope, it is unclear who made that decision. Secrecy fosters suspicions that the contents are dreadful.

The episode may also strengthen the resolve of the mainly English- and German-speaking cardinals who want a vigorous pope to clean up the Curia. This was last reformed under Paul VI, who reigned from 1963 to 1978. Cardinal George Pell, the burly archbishop of Sydney, said he wanted “a strategist, a decision-maker, a planner, somebody who has got strong pastoral capacities already demonstrated so that he can take a grip of the situation.”

For I have sinned

Among those watching the decision making in Rome with apprehension, fear and optimism is the Catholic priesthood. In many countries, their declining and ageing ranks are beset by the revelation of past scandals—both at the parish and at the top. This week Scotland’s most senior cleric, Cardinal Keith O’Brien, admitted that his sexual conduct at times “has fallen below the standards” expected of him. A radio interview by his former counterpart in England and Wales, Cardinal Cormac Murphy O’Connor, marked by a nervous laugh and opaque language, compounded the ire.

Victims of sexual abuse believe the reckoning has barely begun. They want not just proper investigation, but apologies and punishments—and in some cases cash. For them, Benedict exemplified the secretive, cautious response that aggravated the misconduct. It will be hard for any new pope to meet their expectations.

Along with frustrations of church politics and shame about misconduct, attendance at mass is falling. In America it has declined by over a third since 1960. In Britain data from the 2011 census show a similar trend, with numbers of Christians down 12 percentage points since 2001. Average Sunday attendance has fallen for the past 20 years. In mostly Catholic Italy only 39% attend on a monthly basis.

But parish life goes on. Timothy Radcliffe, the former head of the Dominican order, says priests are mostly happy, albeit overstretched. After a peak of 110 vocations in England and Wales in 1996, the figure dropped to a mere 19 in 2006. But this year 38 ordinations are expected. In a reversal of the old days of Western missionaries, many were born overseas. Father Stephen Wang, of Allen Hall seminary in London, counts men from Africa, India and Australia in this year’s cohort of 54.

Movements such as “Youth 2000” and World Youth Day encourage vocations through what has been called “evangelical Catholicism”, says Father Wang, in which the faith is “more confident” about presenting itself. Traditionalist groups such as the Priestly Fraternity of St Peter or the Institute of Christ the King are attracting younger members. The provost of the Brompton Oratory, a traditionalist church in central London, is Father Julian Large, a 43-year-old former journalist who draws a youthful following.

The brighter shore

In some respects the woes of the church in the West seem far away from the parts of the world where it is thriving. In a leafy sanctuary from the heat and frenzy of Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire’s biggest city, Father Aurel da Silva sits under a tree on the tidy front lawn of a monastery. On the wall behind him hangs an oversize portrait of Michel Nielly, who a half-century ago established it as a beachhead for the Dominican order. Today it houses some 30 seminarians from across the region and its small wooden chapel attracts Abidjan’s elites for Sunday mass.

Near the guardhouse, employees raise money for local charities by selling mushrooms that grow in the monastery’s garden. Ceramic water filters distributed to the poor are also displayed prominently. A pink leaflet posted on a bulletin board advertises job-training programmes for unemployed youth. When violence engulfed Côte d’Ivoire after its disputed 2010 presidential election, the towering St Paul’s cathedral in the heart of Abidjan sheltered nearly 2,000 people.

The rapidly growing African Catholic church, says Father da Silva, has great ambitions as a social force. But autonomy must be the watchword. The doctrinal debates and papal intrigue in Rome hardly concern him. “I haven’t spent time in Rome, but I don’t need to,” he says. “What I do here is more important.”

Some of his seminarians have softer attitudes to the Vatican, but they insist that the church’s social message is secondary: spirituality comes first. The African church is no hotbed of liberalism. Its leading contender for the papacy, the Ghanaian cardinal Peter Turkson, is widely regarded as a conservative in the mold of Benedict.

But one of Father da Silva’s older colleagues stakes out a more radical position. The church must evolve, he says. His priorities are: the end of clerical celibacy, women’s ordination, and, above all, greater tolerance for dissent: “You have to accept other people’s way of thinking.”

Those views chime across continents and oceans. In the beautiful, desolate west of Ireland is the village of Moygownagh, the home parish of Father Brendan Hoban. He is a co-founder of the Association of Catholic Priests, which aspires to represent the 2m Irish people who attend mass at least once a month. It is campaigning for an end to celibacy, “inclusive ministry” (code for women priests) and a rethinking of sexual teaching, especially on contraception.

Nearly a quarter of Ireland’s 4,500 priests (and probably a higher share of its able-bodied, energetic ones) has joined. It is in touch with similar bodies in Austria, where a grass-roots initiative among priests incurred a papal rebuke last year, as well as France, the Czech Republic, Australia and the United States.

The Irish association has special credibility. It speaks for a country where the hierarchy is reeling from horrific revelations about abuse in church-run institutions and clerical cover-ups, but where the population, despite the onrush of secularism, remains relatively pious by the standards of the rich world.

The village exemplifies both the crisis and strength of Irish Catholicism. Half of its residents attend weekly mass and most of the remainder look to the church for rites of passage, from first communion to anniversary masses for the dead. Despite the recession, generous donations are paying for church refurbishment.

Moygownagh belongs to a small diocese with 32 priests serving 22 parishes; that number sounds high, and it reflects a flood of vocations in the 1960s and 1970s. But only seven priests are under 55. Father Hoban is nearly 65. When he retires, he expects that the village will be left without a priest of its own for the first time in centuries. In his parents’ time, he recalls, a local farming family would be proud if a son joined the priesthood. Now, he says, even a “faithful Catholic family might panic” if a son announced a similar vocation. “They would feel he was embarking on a life of stress, isolation and low social prestige.”

Almost all the church’s recent woes can be ascribed, in Father Hoban’s view, to the top-down decision-making which has marked the past two papacies. Like many Catholic liberals, he feels that the trouble started when the church hierarchy hijacked the devolutionary reforms of the second Vatican council and blocked change or implemented it badly.

The result, viewed from an Irish village, is that “Rome doesn’t listen to the national bishops; the bishops don’t tell Rome the truth because Rome doesn’t want to hear it; the bishops don’t listen to the priests, the priests haven’t listened enough to the people.” With lay involvement, the child-abuse cover-ups would not have happened. He does not want the church to be “literally democratic”, but nor should it “preserve structures inherited from the Roman empire.”

What do priests of his school expect from the conclave? “In some ways we don’t hope for that much, because all the cardinals have been appointed under the present order. But we hope that some can see the dysfunctionality of the Vatican in its present form…the cardinals need to bite the bullet and appoint somebody who can challenge the Curia.”

Complete Article HERE!