A decade before Bayard Rustin became a chief organizer of the 1963 March on Washington, the civil rights activist was booked into a Los Angeles County jail on suspicion of “lewd vagrancy.”

On that night in January 1953, hours after Rustin had given a speech in Pasadena, Calif., police officers spotted him in a parked car, having sex with one of the other two men in the car. Rustin was sentenced to 60 days in jail and forced to register as a sex offender for the “morals charge,” which was often used to target gay people in those years.

Rustin would ultimately become one of the key leaders of the civil rights movement. He advised the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. on nonviolent tactics, helped organize the Montgomery, Ala., bus boycott and helped create the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. But the arrest remained a stain on his record, nearly exiling him from the movement he helped build.

Now, on the anniversary of his arrest, lawmakers in California are asking Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) to posthumously pardon Rustin and “right this wrong.”

“There’s a cloud hanging over him because of this unfair, discriminatory conviction, a conviction that never should have happened, a conviction that happened only because he was a gay man,” said state Sen. Scott Wiener, chair of California’s legislative LGBTQ caucus.

In a news conference Tuesday, Wiener joined with Assemblywoman Shirley Weber, chair of the state’s legislative black caucus, to formally ask the governor for the pardon.

While the state has repealed many of the discriminatory laws that targeted black and LGBTQ people such as Rustin, Wiener wrote in a letter to the governor, “we must acknowledge and make amends for the harm that California’s past actions have had on so many people. Pardoning Mr. Rustin will be a positive step toward reconciliation.”

In response, Newsom released a statement Tuesday afternoon saying he “will be closely considering their request and the corresponding case.”

“History is clear. In California and across the country, sodomy laws were used as legal tools of oppression,” Newsom said in the statement. “They were used to stigmatize and punish LGBTQ individuals and communities and warn others what harm could await them for living authentically. I thank those who are advocating for Mr. Bayard Rustin’s pardon.”

Wiener came up with the idea over a breakfast with longtime LGBTQ activist Nicole Ramirez, who has spent years seeking a postage stamp dedicated to Rustin. Ramirez said he has heard concerns from some officials that Rustin’s arrest record could get in the way of the stamp approval process.

The stamp, Ramirez said, would help honor a leader who paid a steep price for living authentically as a gay man at a time when he could be arrested, fired and even hospitalized for his sexuality.

“For him to come and speak out and be openly gay, can you imagine that?” Ramirez said. “He was subjecting himself to more than that arrest but to commitment to a state hospital.”

Ramirez met Rustin briefly during a march in Washington in 1987, shortly before Rustin’s death. But at the time, Ramirez didn’t know who Rustin was, he said.

For decades, Rustin has been overlooked as a key strategist of the civil rights movement, historians say.

“Early on, he wasn’t so well known because the civil rights leaders tried to keep him in the shadows … they were fearful of being tainted by Bayard’s gay sexuality,” said Michael Long, who wrote a young-adult book about Rustin and edited a collection of letters by the civil rights leader.

After his arrest in California in 1953, Rustin’s career nearly derailed. He was forced to cancel all upcoming speaking engagements and resign from his position with a pacifist organization, the Fellowship for Reconciliation, Long said. He struggled to find work, and even began doing manual labor as a furniture mover, said Walter Naegle, Rustin’s partner for the last decade of his life.

Naegle described the fallout from his arrest as a “very dark period.”

“I remember him saying he would be walking around in the streets and checking phone booths for loose change,” said Naegle, now 70.

Rustin had been arrested before, for nonviolent protests that included refusing to leave white areas of local movie theaters and restaurants. But it was this arrest that was used to humiliate him and tarnish his reputation. While Rustin never hid his sexuality, he was deeply aware of the way it could affect his work.

In a letter written in March 1953, about three months after his arrest, Rustin wrote: “I know now that for me sex must be sublimated if I am to live with myself and in this world longer.”

Rustin eventually landed a role with the War Resisters League, launching him back into the civil rights movement, Long said. But his sexuality continued to threaten to sideline him. In 1960, after threats from powerful Rep. Adam Clayton Powell (N.Y.), King pushed Rustin out of his inner circle, and Rustin resigned from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

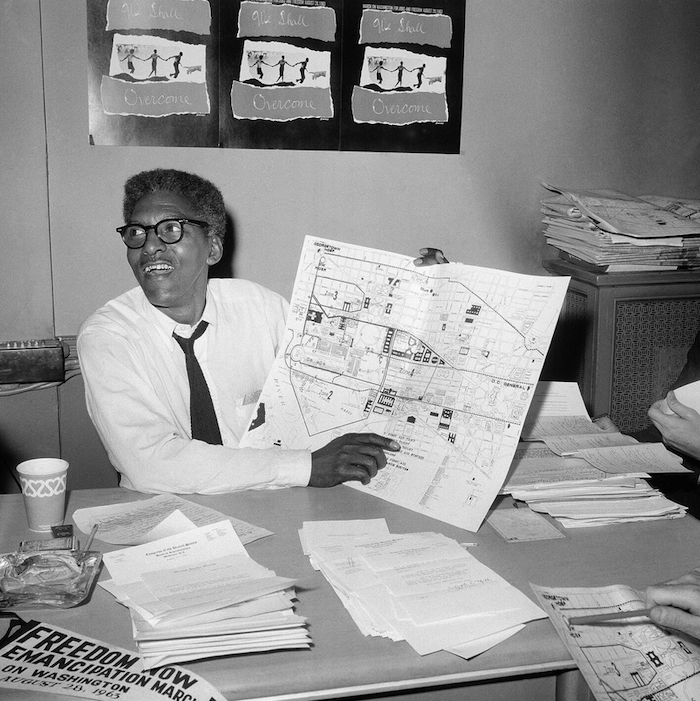

But then, in 1963, as leaders planned the March on Washington, Rustin’s longtime mentor, A. Philip Randolph, appointed him as a key organizer of the gathering. Rustin was tasked with steering the logistics of the massive event, coordinating between civil rights groups and recruiting off-duty law enforcement personnel to serve as marshals.

As the march approached, Sen. Strom Thurmond (S.C.) attacked “Mr. March-on-Washington himself” on the Senate floor, dredging up Rustin’s arrest record from Pasadena.

“The words ‘morals charge’ are true. But this again is a clear-cut case of toning down the charge,” Thurmond said on the Senate floor. “The conviction was sex perversion and a subsequent arrest of vagrancy and lewdness.”

But this time, the organizers of the march — including King — stood by Rustin. And even as his sexuality was repeatedly used against him, Rustin never shied away from it, Naegle said.

“They really picked the wrong guy,” Naegle said. “The thing that separated Bayard from many people was he wasn’t going to be silenced.”

In a recently released interview with the Washington Blade, Rustin said: “It was an absolute necessity for me to declare homosexuality because if I didn’t I was a part of the prejudice. I was aiding and abetting … the prejudice that was a part of the effort to destroy me.” He couldn’t be a “free whole person,” he said, living in the closet.

The week after the March on Washington, the cover of Life magazine featured not a photo of King, but of Randolph and Rustin, standing in front of the Lincoln Memorial.

More than two decades later, upon his death in 1987, Rustin’s obituary was featured on the front page of the New York Times, identifying him as a civil rights activist and chief organizer of the March on Washington.

But it barely mentioned his identity as a gay man. In the obituary, Naegle was referred to not as Rustin’s partner but as his “administrative assistant and adopted son.”

It wasn’t until recent years that Rustin began to receive recognition not only as a major civil rights leader but as a rare example of an openly gay leader at the time.

Ahead of the 50th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington, Naegle traveled across the country organizing programs dedicated to spreading the word of Rustin’s legacy. And in 2013, Obama posthumously honored Rustin with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, noting his role as an openly gay African American who “stood at the intersection of several of the fights for equal rights.”

A pardon from the California governor would represent much more than personal vindication for Rustin, Naegle said. It would recognize the injustice and damage done to scores of other members of the LGBTQ community who never received the same level of recognition as Rustin.

“He survived, he thrived, he did fine, but there were a lot of people that didn’t,” Naegle said.

To Long, a pardon would be “an affirmation of what Rustin knew all along: that he was not a criminal for being gay.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!