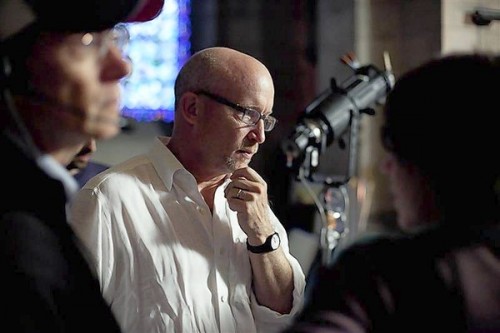

Robert C. Mickens, Vatican correspondent and columnist for “The Tablet,” speaks about The Vatican’s implosion and what it means for Catholics.

Film defrocks church hierarchy over handling of sex abuse

By Andrea Burzynski

Four deaf Wisconsin men were some of the first to seek justice after suffering childhood sexual abuse at the hands of a priest, and a new documentary about the Catholic Church’s poor handling of such cases stemming from the Vatican seeks to make their voices heard.

“Mea Maxima Culpa: Silence in the House of God” explores the impact of the Roman Catholic Church’s protocol as dictated from the Vatican for dealing with pedophile priests. It opens in U.S. cinemas on November 16, and will air on cable channel HBO in February.

“Mea Maxima Culpa: Silence in the House of God” explores the impact of the Roman Catholic Church’s protocol as dictated from the Vatican for dealing with pedophile priests. It opens in U.S. cinemas on November 16, and will air on cable channel HBO in February.

Though American media coverage about child sex abuse by clergy has been extensive since a slew of cases came to light in Boston in 2002, Oscar-winning documentary director Alex Gibney wanted to connect individual stories with what he sees as systemic failures stemming from the top of the church.

“A lot of individual stories had been done about clerical sex abuse, but I hadn’t seen one that really connected the individual stories with the larger cover-up by the Vatican, so that was important,” Gibney told Reuters in an interview.

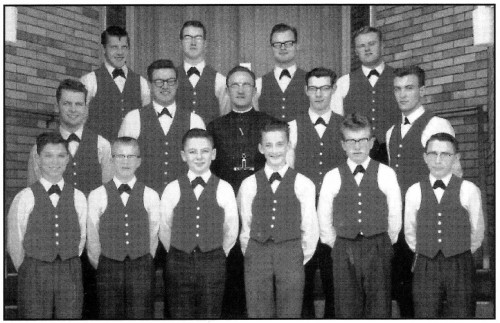

The film centers on the group of deaf men and their experiences as young boys attending St. John’s School for the Deaf in St. Francis, Wisconsin.

In a letter to the Vatican in 1998, the late Rev. Father Lawrence Murphy admitted abusing some 200 deaf boys over two decades beginning in the 1950s.

Murphy claimed he had repented, and asked to live out his last years as a priest, and was never defrocked or punished by civil authorities. He died in 1998.

In the film, the men communicate their frustrating attempts to bring their experiences to the attention of religious and civil authorities with effusive sign language and facial expressions, paired with voiceovers by actors such as Ethan Hawke.

The film also traces a convoluted bureaucracy – right up to the cardinal who is now Pope Benedict – to reveal a set of policies that the film portrays as often seeming more interested in preserving the Church’s image.

STRUGGLING TO BE HEARD

“These were deaf men whose voices literally couldn’t be heard, so there was a silence from them, and there was also this silence coming from the church, a refusal to confront this obvious crime, in part because they were covering it up,” said Gibney.

The Vatican has denied any cover-up in the Murphy case and in 2010 issued a statement condemning his abuse. It has criticized media reports about the Church’s handling of the cases as anti-Catholic.

Contrasting that, the film shows interviews with former church officials who talk openly of church policies to handle cases by “rehabilitating” abusive clergymen and snuffing out scandal.

Gibney said that all of the Vatican officials he contacted declined his interview requests.

Raised Catholic himself, Gibney no longer practices organized religion, but empathizes with Catholics who feel a sense of loyalty to the religion’s institutions and acknowledges that criticism of the church can feel like a personal attack.

“Mea Maxima Culpa,” a Latin phrase meaning “my most grievous fault” focuses on the failures of the Catholic Church’s hierarchy. But Gibney – who won an Oscar for “Taxi to the Dark Side” – said the film’s theme transcends religion and is also relevant for secular institutions.

“This is obviously about the church, but it’s also a crime film,” he said. “It’s about abuse of power and it’s about how institutions instead of reckoning with problems try to cover them up. It’s always the cover-up that creates the problem.”

He cited the Jerry Sandusky sex abuse scandal that rocked Penn State University recently, and the BBC’s poor handling of abuse allegations against the late British TV personality Jimmy Savile as examples of secular institutions brought low by similar issues.

“The thing about predators is that they tend to hide in plain sight,” Gibney said. “You’re seeing it now with Sandusky, you’re seeing it now with Jimmy Savile in Great Britain, and you saw it with Father Murphy in the film.”

Gibney thinks that the public’s stubbornly rosy perceptions of charismatic authority figures, including priests, is a major factor in such scandals.

“They’re often involved in charity or good works,” he said of high-profile abusers. “That seems to give you license to do unbelievable things because people cut you all sorts of slack that they wouldn’t normally do for other people.”

Complete Article HERE!

Quote of the Day

“When you rape children, cover it, rape them again, cover it up, rape them again, finally get caught, still cover it up, apologize, recant your apology, then blame the victim, you have zero moral authority to lecture others about their supposed sins.”

– John Aravosis at AMERICAblog, writing about the Catholic Church’s most current bit of pearl-clutching over marriage equality.

Six men suing the Catholic church for alleged sexual abuse

A group of men from a northwestern Ontario First Nations community are suing a Winnipeg-based Roman Catholic order and others to seek redress for alleged sexual abuse they suffered at the hands of their community priest as young boys.

The six men from the Lac La Croix First Nation near Fort Francis seek unspecified financial damages from the federal government, a Catholic diocese in Thunder Bay and the order of Les Oblats de Marie Immaculee du Manitoba, along with a priest who lived and worked on the reserve in the 1960s.

The six men from the Lac La Croix First Nation near Fort Francis seek unspecified financial damages from the federal government, a Catholic diocese in Thunder Bay and the order of Les Oblats de Marie Immaculee du Manitoba, along with a priest who lived and worked on the reserve in the 1960s.

The men range in age from 55 to 61.

In separate statements of claim, each alleges his life has been deeply and negatively affected by the aftershocks of sexual assaults he was subjected to — abuse the men say they felt powerless to speak out about given the priest’s position of power in their small community.

One man states that when he was 10 or 11 years old, the priest took him to his on-reserve home several times during the summer months and anally raped him. The behaviour continued until he was 13 or 14, the now-56-year-old says.

The other men make similar claims, one alleging he was abused more than two dozen times at the priest’s home and in a schoolhouse room. Another claims he was assaulted by the priest in a hotel room during a trip to Minnesota.

The priest died in May 1986.

The allegations have not been proven, and no statement of defence has been filed. No court date has been set to test the men’s claims.

The men state the Order and the Thunder Bay diocese should be held indirectly responsible for the actions of the now-late priest, who was a member of the order and an employee of the diocese, their lawsuits say.

“The Order and the Diocese held out (the priest) as an individual that embodied the values of the Roman Catholic faith such that it was implied that he could be trusted and that he would do no harm,” one lawsuit states.

The two organizations should have known there would be a “power imbalance” given the emphasis the faith places on obeying the wishes of its clergy, and the power the priest had over the “immortal souls” of the faithful in the community.

Complete Article HERE!

MEA MAXIMA CULPA SILENCE IN THE HOUSE OF GOD

Alex Gibney, an award-winning documentary maker whose work has focussed on Lance Armstrong, Julian Assange, and Enron, has found his most contentious topic yet.

His Oscar-touted exposé, Mea Maxima Culpa: Silence in the House of God, traces a sex-abuse scandal from a Milwaukee Catholic church to the Vatican.

Gibney also shot parts of the film in Ireland and Italy and received €50,000 from the Irish Film Board. The movie was banned by the Venice and Rome film festivals this year.

According to the New York Post, Gibney said of its rejection: “I was disappointed. The Vatican exerts a very strong influence in Italy. There is a palpable sense of fear there. This film takes on the Vatican’s complicity [in covering it up].”

The film won the best documentary prize at the London Film Festival last week.

It was co-produced by Belfast’s Below the Radar production company, and is in cinemas in the US from Nov 16.

It follows the story of Fr Lawrence Murphy at the St John’s School for the Deaf in Wisconsin, who molested 200 pupils for 24 years. He was never disciplined, even after his actions were brought to the attention of the Vatican. Instead, he was moved to other schools.

“The direct connection of the Vatican to this sheds light on the way they’ve shoved this stuff under the carpet,” said Gibney, who discovered a similar scandal involving deaf students in Verona in Italy while making the film.

Five students are interviewed in the film, and, as they use sign language, their words are voiced by actors.

Gibney said: “We play with the idea of silence in this film. How could this predatory behaviour exist with people so helpless?

“With the priests in Italy… there is very little sympathy for victims.

“Instead, there’s this resentment that people would attack the Church. What else is in this huge cache of documents in the secret Vatican archives that has been compiled for centuries?”