By Angus MacSwan

Ray Mouton was a successful young lawyer in Lafayette, Louisiana, respected in the community and blessed with a loving family, when he received a call from a vicar in the Roman Catholic diocese for a lunch meeting on a fateful day in 1984.

The diocese asked him to defend an errant priest, accused of abusing dozens of children in a rural community. Mouton reluctantly agreed to take on the task.

What followed over the next few years was the uncovering of an institution riddled with pedophile priests on a national scale and efforts at high levels in the Catholic Church to hide the problem away.

For Mouton, it meant the end of his law career, health problems, and anger, depression and guilt.

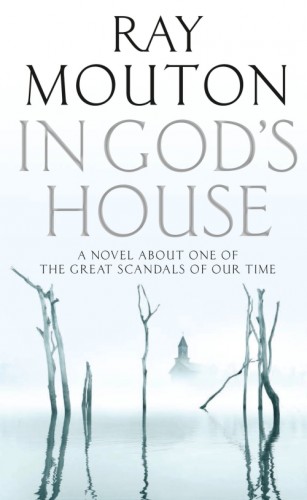

After many years of writing from his self-imposed exile in France, he finally tells his story in the novel “In God’s House“. It is a harrowing read laden with sickening detail, but also for Mouton, a work of atonement.

“There’s not a day I don’t think about the children. When I was writing the book, whenever I wanted to quit, I thought about the victims and their families,” he told Reuters.

“There’s not a day I don’t think about the children. When I was writing the book, whenever I wanted to quit, I thought about the victims and their families,” he told Reuters.

In person, Mouton, now aged 65, looks like a southern lawyer from central casting, with a head of thick white hair and a sonorous Louisiana drawl.

He chose to tell the story in novel form although the characters, from the lawyer to a senior Vatican official who proves an obstacle to addressing the scandal – are based on real figures.

“The novel is a dramatic experience. My experience was a traumatic one. Every day there were revelations. I didn’t want to believe, the country didn’t want to believe,” he said.

Mouton and his family – Cajuns whose ancestors came to Louisiana as part of the Acadian diaspora – were strongly Catholic. His family had donated land for the cathedral in Lafayette and built schools, churches and a seminary.

When he first agreed to defend the priest, Father Gilbert Gauthe, he believed he was dealing with an isolated case.

“I believed priests were somehow superior. I had never heard of a priest having sex with a child. I could not believe a Catholic priest could do this. I thought he was just one then it all unraveled. In that diocese alone there were a dozen more.”

The church preferred to deal with the problem by paying off victims’ families. But one family wanted to see justice done.

As a lawyer, Mouton believed Gauthe had the right to a fair trial. He soon realized the church was deeply compromised. It had known about Gauthe’s crimes since his days in seminary but had moved him around various parishes, where the abuses continued.

The church was in effect harboring criminals, Mouton said.

“I did start out on the side of the church. I couldn’t imagine they had foreknowledge,” he said.

Mouton joined forces with Father Tom Doyle, a canon lawyer in the Vatican Embassy in Washington, and Father Michael Peterson, a psychiatrist priest who treated sexually deviant clergymen. The two had heard many other cases across Louisiana and the United States – and attempts to bury the problem.

Believing they had the support of the church hierarchy, they set out on a crusade to bring it into the open and seek justice for the victims.

They spent a year working on a document detailing the scale of the abuse, the steps the church should take to address it and the consequences if it did not. It stated that there was a national crisis involving dozens, if not hundreds, of priests.

“It told them what the deal was – you’ll lose 1,000 priests and a billion dollars.”

They hoped to present the document to the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops for debate. But after a meeting in a Chicago hotel in 1985 with a cardinal, they were told to kill it.

“They put the reputation of the church above the value of the little children. They did all they could to avoid scandal.”

FALL FROM GRACE

“In God’s House” details a powerful apparatus at work involving local politicians, expensive lawyers, insurance companies and bishops. It also reached into the Vatican, which Mouton says considered the institution above the law.

It also shows the devastation of the victims and their families – shame, anger and frustration as well as physical damage. Many were told that to seek redress would be disloyal to the church, adding further conflict to their emotions.

Mouton himself suffered verbal abuse and even death threats in the community for defending Gauthe. He was accused of trying to extort the church for exorbitant fees.

He put up an insanity plea for Gauthe but the priest himself insisted he was sane. He was sentenced to 20 years.

However, a senior jurist in Louisiana involved himself personally in Gauthe’s case. Instead of going to a prison that was a treatment facility for pedophiles, the priest was sent to a prison where juveniles were held. He was released after serving only half of his sentence.

Gauthe was picked up in Texas soon after his release for molesting a 3-year-old boy, but put on probation rather than being sent back to prison.

Mouton’s marriage broke up and he became an alcoholic.

“It was a cataclysmic event. It broke me in half. I did fall from grace,” he said.

It took many years but subsequent events have vindicated Mouton as widespread sexual abuse by priests came to light across the United States and the world, from Ireland to Australia.

The church and its insurance companies have paid out more than $2 billion dollars in the United States, bishops have been disgraced, and its reputation has suffered to the point that the faithful have deserted in droves.

Mouton now lives in southern France close to the Pyrenees with his second wife Melony and travels frequently to Spain, Mexico and other countries.

He is still bitter about the cover-ups and that many of those responsible have never been brought to justice. Nor has the problem been eradicated, he believes.

“I don’t think we’ve reached critical mass on it yet. The question is what can the church do? The church needs to release all the documents and demand the resignations of those involved.”

The novel is dedicated to Scott Anthony Gastal, the first child to testify in court against a bishop, and to the victims and their families, who, he says, “were abandoned not by their God, but by their Church”.

“I was haunted by my experience. I felt I had to do something,” he said.

Complete Article HERE!