By Peter Smith

The day began with a 30-year-old witness describing how Franciscan Brother Stephen Baker befriended him and his family and repeatedly molested him from his early teens.

But even as prosecutors laid out their case involving the late friar’s molestation of as many as 100 youths at Bishop McCort Catholic High School in Johnstown and elsewhere, the attorneys for three of his former superiors launched a vigorous defense at a preliminary hearing here Thursday.

Their clients, former minister provincials for a Hollidaysburg-based Franciscan province, face charges of conspiracy and endangering the welfare of children for assigning Baker to Bishop McCort and other ministry posts where he had regular contact with youths between 1992 and 2010. The charges followed last month’s release of state grand jury reports about the order and the surrounding Diocese of Altoona-Johnstown.

The attorneys not only argued that the statute of limitations should preclude the Franciscans’ prosecution, but they also managed to exclude a crucial piece of evidence from the hearing — internal notes from 1992 referring to restrictions on Baker’s contact with minors — and to cast doubt on the timing of when the Franciscans learned of another allegation against Baker in 2000.

All this took place Thursday at a day-long hearing before Blair County District Judge Paula Aigner to determine the strength of the prosecutor’s case. With testimony still in progress at day’s end, Judge Aigner recessed the hearing until April 27.

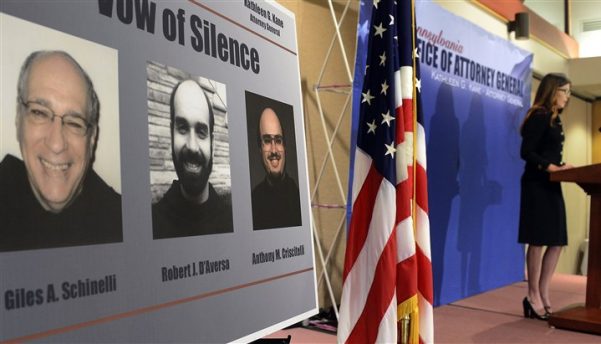

Charged are the Very Revs. Giles Schinelli, 73, who was minister provincial from 1986 to 1994; Robert J. D’Aversa, 69, who was minister provincial from 1994 to 2001; and the Very Rev. Anthony M. Criscitelli, 61, who was minister provincial from 2002 to 2010. They led the Franciscan Friars, Third Order Regulars of the Immaculate Conception Province.

All three sat impassively in dark clerical garb behind their lawyers.

Brother Baker committed suicide in January 2013 at the Hollidaysburg monastery when the enormity of his offenses became publicly known.

Deputy Attorney General Daniel Dye began the day by calling the 30-year-old witness, whose name was not disclosed.

The man said that Brother Baker worked as an athletic trainer and told Bishop McCort students to strip down and get on the training table, where he would fondle them and digitally penetrate them.

He said this practice was commonly known among athletes.

“After a while, it got normal,” he said.

He said that the nickname students gave the practice was “a bro job” because Brother Baker’s nickname was “Bro.” He said he was also abused by Baker in car trips and at the monastery.

But much of Thursday focused on what Baker’s supervisors knew and when they knew it.

Special Agent Jessica Eger of the state Bureau of Criminal Investigation testified about more than 30 documents seized from the order last year via search warrant.

The documents showed that Father Schinelli was aware of an accusation against Baker stemming from Baker’s work in Missouri and sent him for a 1992 psychological evaluation that found no evidence of any sexual pathology or risk to minors.

But handwritten notes by Father Schinelli indicated that the same psychologist recommended Baker have no ministry involving one-to-one contact with minors, nor to take any overnight trips with them — activities the earlier witness said were routine.

However, attorney Charles Porter, representing Father Schinelli, convinced Judge Aigner that these notes should be excluded because they were part of correspondence with the order’s lawyer and were protected by attorney-client privilege. Mr. Dye unsuccessfully argued that such privilege doesn’t apply under the “crime-fraud exception.”

“This is a crime in progress,” he said.

Mr. Porter went on to say Father Schinelli tried unsuccessfully to get more information to evaluate the Missouri allegation. Baker, he said, “duped” the psychologist that his client relied on.

Ms. Eger acknowledged there was no other documentary evidence that Father Schinelli, while in office, knew of any allegations against Baker.

Next up was attorney Robert Ridge, representing Father D’Aversa. Father D’Aversa himself had testified to the grand jury last year that he removed Baker from Bishop McCort after receiving a credible allegation in early 2000 of past abuse by Baker.

As Baker was being reassigned, Father D’Aversa wrote him: “Thank you for your efforts in the educational Apostolate. You have done an excellent job.”

Father D’Aversa put Baker in charge of vocations, through which he engaged in multiple overnight retreats with teens in mid-2000.

But Mr. Ridge questioned prosecutors’ reliance on his own client’s memory. He noted that there is no documentary evidence that Father D’Aversa knew of that allegation until November 2000, when he put Baker on more restrictions.

The hearing ended with testimony about Father Criscitelli’s tenure and conflicting claims about how well those restrictions were actually enforced.

Baker worked at a Catholic gift store known as the Friar Shop at the Altoona Mall. In 2006 when the order was seeking accreditation for compliance with safe-environment standards by an outside firm, the order was told it needed better controls on Baker’s access to children while at the mall. Father Criscitelli, in a document, sought ways to cushion the impact on Baker so as not to “alarm” co-workers.

And as late as 2006, Baker was still volunteering at St. Clare of Assisi Church in Johnstown, despite a 2002 Catholic Church policy against confirmed abusers being in ministry after 2002. The order took pains not to depict Baker’s Friar Shop work as “ministry.”

Some documents showed the order supervisors being sensitive to Baker’s feelings about his ministry restrictions, noting he got very defensive and would submit only when required to psychological care. Baker, according to one mental-health evaluation, felt “aggrieved and violated because of these allegations” and claimed one of his victims was “effeminate” and misunderstood his actions.

One letter from a minister provincial cited the need for restrictions to safeguard the integrity of Baker and the province, and “the resources of the province.”

Such comments infuriated Barbara Aponte of Poland, Ohio, who attended the hearing and who attributes her son’s suicide to his abuse by Baker when he worked at an Ohio Catholic high school.

The documents “always express concern for minimizing (damage to the order’s ) public image and financial liability,” she said. “There’s never a mention in these documents about the welfare of the kids and the safety of the kids.”

Complete Article HERE!