By

Shaun Dougherty’s story begins on page 66 of the grand jury report into widespread child sexual abuse in the Altoona-Johnstown Diocese.

That page – one of 147 pages in the report detailing accusations against more than 50 religious leaders, priests and teachers – begins the account into the investigation of George Koharchik, a longtime priest, who among other diocesan assignments, was pastor at St. Clement Church in Johnstown for a decade.

That’s where Dougherty, then an altar boy, attended school and Mass with his parents.

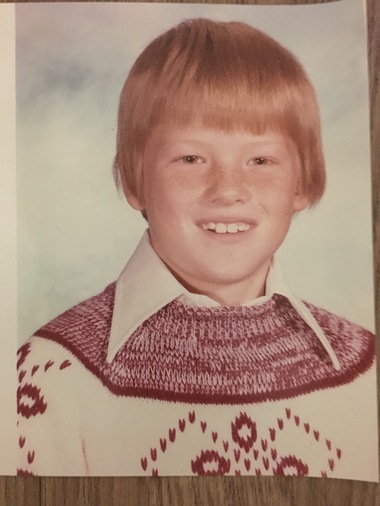

The second youngest of nine kids, Dougherty was 10 and a fifth-grader at St. Clement School when he met Koharchik in 1980. Koharchik was his basketball coach and his religion teacher. The priest spent an inordinate amount of time with the boy.

By the time the priest had finished “grooming” him, Dougherty was allowed to “drive” the priest’s car. Koharchik would sit the boy close to him — or on his lap — and give him control of the steering wheel. Whether Dougherty, or one of his friends in the car, whoever had his hands on the wheel could count on Koharchik’s hands to grope their body and eventually their penis, Dougherty said.

“My first erection was at the hands of Koharchik,” he said. “My first memory of an ejaculation was with Father Koharchick.”

Dougherty played racquetball, cycled and played soccer with the 40-something priest.

“Any activity that required a shower afterward,” Dougherty said. “He bathed me. He cleaned my entire body.”

What began as tickling led to fondling and by the time Dougherty was 13 to digital penetration, he said.

“I remember shooting him a look,” Dougherty said. “But nothing was said, nothing was ever discussed about it.”

Koharchik sexually molested him for three and a half years, Dougherty said.

A preferential sex offender

Koharchik on March 17, 2015, testified before grand jury investigators that he had sexually molested boys while at St. Clement. In a contentious exchange, Koharchick told investigators how he had for years slept and showered with minors, how he had children sit on his lap and how he “patted” the buttocks of young boys.

Koharchik offered only clipped answers to the aggressive questions from investigators.

“I didn’t think of it certainly as predatory,” he told the investigators. “I don’t know that I would speak of it as acts of love.”

Investigators in March concluded Koharchik was a “child predator” who molested children after “desensitizing” them to sexual topics for his own sexual gratification.

A special agent from the FBI assigned to investigate the allegations designated Koharchik as a “preferential child sex offender,” who was able to use the trust and authority of the priesthood to “secretly engage in molestation, digital penetration and anal sex with children.”

Koharchik had normalized the conduct, nudity and contact to “confuse and condition” the boys for sexual assault, investigators concluded. Koharchik also groomed their families. He bowled with Dougherty’s parents every Thursday night for years.

Now 46, Dougherty is married and a successful chef and owner of the Crescent Grill in Long Island City, N.Y. He splits his time between homes in New York and Johnstown.

Gone is the mop of red hair that framed his freckled face as a boy. Gone is his faith in his religion, and most of his faith in God.

Dougherty says he is no different than other victims of child sexual abuse. He has endured the pain, the trauma, substance abuse, a suicide attempt. But he counts himself among the lucky ones who have negotiated the ravages of abuse to forge a life.

The torment and the pain are just beneath the surface, though.

In recent months, the venom of his abuse has resurfaced amid the reports from the investigation by the Attorney General’s Office into systemic child sexual abuse and its cover-up in the Altoona-Johnstown Diocese. Investigators combed the secret archives of the diocese and heard testimony from victims, as well as church officials and priests, concluding that hundreds of children across the diocese had been sexually molested by priests and church officials from the diocese starting as far back as 1950.

The grand jury report could not recommend criminal charges against any individuals associated with the diocese as all criminal statute of limitations had expired. The same was true for civil cases.

“None of them are registered sex offenders. None of them,” Dougherty said. “They can move next to anybody. They can move next to any school. Plus the Senate just gave them a green light said: ‘Here you go. Here you go. You are free. We are on your side.'”

Dressed in jeans, a Polo plaid shirt and blue jacket, Dougherty was in Harrisburg this week, primarily to try to understand the looming fate of a bill that could, after 36 years, allow him to seek justice against his predator.

For the past several months, Dougherty has been following the reports on House Bill 1947, the reform legislation that is poised to overhaul Pennsylvania’s child sex crime laws. The bill – which sailed out of the House in April by a 180-15 vote – passed the Senate last week, but only after being stripped of the retroactive measure that would have allowed Dougherty to seek legal recourse against Koharchik.

“Whoever is in this report that’s molesting a child today, we won’t know about it for 20 years,” says Dougherty slamming his hand on the thick grand jury report. “We have them … today. We have the system, today. We have them admitting it, today. We’re just going to open the door and let them all out. ‘Here you go.’ No sex offense charges.”

Like almost all victims of clergy sex abuse, Dougherty blames the church for the fate of the bill. He said the church, and its powerful legislative arm, the Pennsylvania Catholic Conference, have the ear of lawmakers in the General Assembly .

“I struggle with a belief in God but I have a belief in our government system,” Dougherty said. “I don’t believe it was fairly done.”

Dougherty railed against Senate President Pro Tempore Joe Scarnati, R-Jefferson County, who introduced the amendment to stripped the retroactive measure from the bill. Scarnati argued that it was unconstitutional to revive expired statute of limitations, the conclusion delivered by the state Solicitor General Bruce Castor during a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing on the bill.

“That is his interpretation,” Dougherty said of Scarnati’s opinion on the constitutionality of the bill. “He is not a judge. He is a legislator. It should have gone to the Senate floor clean. Let the courts decide.”

PennLive submitted a request to interview Scarnati. The request has not been granted.

The Pennsylvania Catholic Conference notes that the Catholic community “has consistently enforced strict safe environment policies” and offered assistance to survivors and their families. To date, dioceses across the state have spent more than $16.6 million on victim/survivor assistance services to provide “compassionate support to individuals and families.”

“The Catholic Church has a sincere commitment to the emotional and spiritual well-being of individuals who have been impacted by the crime of childhood sexual abuse, no matter how long ago the crime was committed,” reads the conference’s official statement.

A priest defrocked

In 2012, contacted by detectives investigating allegations of child sex abuse against Koharchik, Dougherty provided information to the Cambria County law enforcement officials. Dougherty is convinced his responses were read to Koharchik in front of the grand jury.

“I believe with all of my heart that my name is one of those redacted,” Dougherty said. One week after speaking with detectives, Dougherty was contacted and told the information was being turned over to the state.

Koharchik was placed on leave in August 2012 amid accusations of sexual misconduct involving minors dating back more than 30 years. At the time, he was pastor at St. Catherine of Siena in Mount Union, Huntingdon County.

“At that time those accusations had just been presented. It was not like an old case that was being reviewed,” Tony DeGol, the spokesman for the Diocese of Altoona-Johnstown said. “When accusations were brought, (Bishop Mark Bartchak) immediately placed George Koharchik on leave.”

On Jan. 22, 2016, Koharchik was defrocked.

“The Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith in Rome requested that George Koharchik seek laicization,” DeGol said, reading from the former priest’s file. “When he did, it was granted by Pope Francis.”

Koharchik lives in Johnstown as a private citizen. His home is less than a 5-minute walk from Johnstown Public Middle School on Garfield Street.

PennLive on Thursday reached Koharchik at his home. He declined to answer any of the questions to put to him. “I have no comment,” he repeated on the phone.

Dougherty, who retains a youthful spark in his eyes and fills a room with his voice, succumbs to tears recalling how his father told him he finally believed him before he died. He chokes up recounting the call from his mother, now 83, a few years ago telling him she believed him. Koharchik was all over the local paper. The diocese was taking action against him amid accusations of child sex abuse.

Koharchik bears no hard feelings for his parents. They were devout Catholics living within the teachings of the church, he said.

“Give us our shot”

On Monday evening, Dougherty read PennLive’s report on the suicide death of Brian Gergely, who like him, was one of hundreds of victims of clergy child sex abuse from the Altoona-Johnstown Diocese.

Dougherty said that even though he never met Gergely, he felt as if he had lost a relative. He checked into a hotel and bawled his eyes out.

“I felt so absolutely defeated and so absolutely pissed off,” Dougherty said. “Just exactly the way Brian felt. They are doing it again … except this time they did it blatantly in the paper. They publicly (expletive) us again, they just did it publicly.”

A successful businessman, Dougherty said he would not sue to seek money, but rather for moral principle.

“If I was a sitting senator for 30 years, I would be standing on my Senate desk on the floor screaming at the top of my lungs, ‘Help me please! They have duped all of us. The children in my district are being raped by people who were supposed to teach them the teachings of Jesus Christ … show some teeth, senator.”

He implored lawmakers to salvage the retroactive measure of the bill, which moved from the Senate last week back to the House for a concurrence vote. If, down the road, the courts rule the bill unconstitutional, Dougherty said, he’ll take that loss and move on.

“Give us our shot,” he said. “Give us our shot.”

Complete Article HERE!