— Only 25% are on archdiocese’s credibly accused list

The number of abuse claims – 310, spanning several decades – have been kept from public as archdiocese undergoes bankruptcy proceedings

More than 300 people employed by Roman Catholic institutions in the south-eastern US city of New Orleans have been accused of sexually abusing children or other vulnerable people whom they met through their work over the last several decades, secret documents obtained by the Guardian reveal.

Though New Orleans’s 230-year-old archdiocese has spent a significant portion of its recent history managing the fallout from its association with the worldwide Catholic church’s clerical molestation scandal, the organization has generally sought to keep hidden the exact number of priests, deacons, nuns, religious brothers and lay staffers – such as parochial school teachers – under its supervision who have been named in abuse claims.

A memorandum which attorneys for victims of clerical sexual abuse prepared and handed to law enforcement in the latter part of last year arguably gives the clearest idea yet of the number of accused abusers working over the last five decades or so in a region that is home to about a half-million Catholics. The brief summarizes evidence of what its authors believe are crimes that could still be prosecuted.

And while the 48-page document has not led to any substantial action from authorities, it shows how the archdiocese itself only finds roughly a quarter of the allegations against its clergymen to be credibly accused, which is well below what research estimates is the norm for sexual abuse claims to be found false or unprovable.

The memo additionally asserts that the archdiocese has referred fewer than two dozen of its accused clerics to law enforcement, on average waiting nearly two decades to do so.

The memo alludes to secret internal archdiocesan records that were handed over after the local church sought federal bankruptcy protection in 2020 in response to a wave of abuse-related lawsuits. Because confidentiality rules govern the bankruptcy, both church officials and advocates for molestation victims have worked to keep the memo hidden from public view.

The Guardian, however, obtained a copy of that memo.

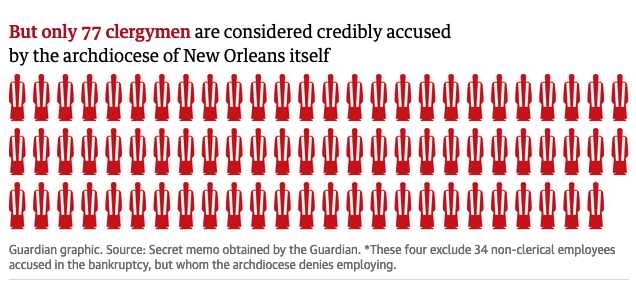

For nearly five years now, the New Orleans archdiocese has curated a list of 77 priests and deacons whom the organization considers to be credibly accused. Officials maintain that the roster, first released by Archbishop Gregory Aymond in 2018, resulted from an extensive, ongoing internal review of files concerning the careers of more than 2,300 clerics, which was meant to fulfill promises of transparency spurred on by the abuse crisis.

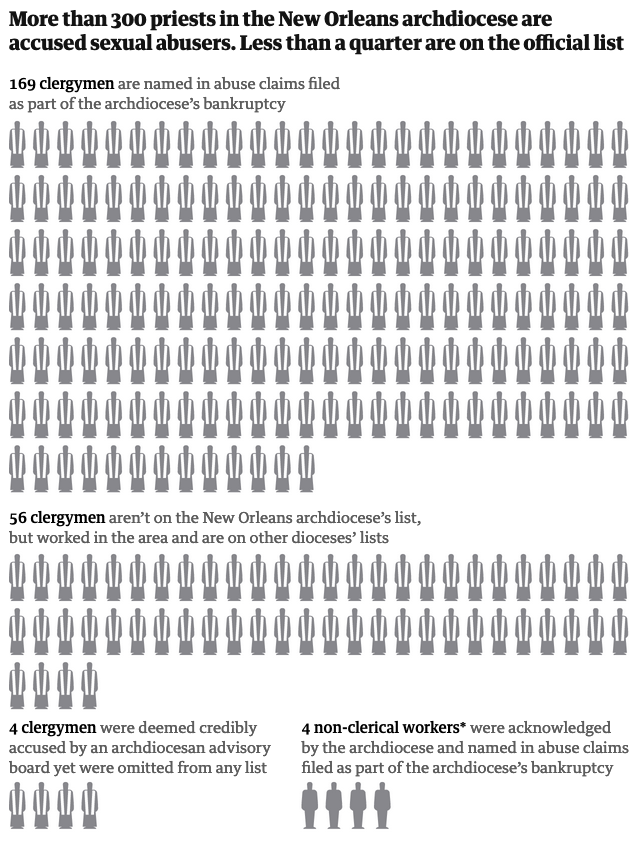

But there are at least 56 other priests and deacons who worked at institutions overseen by – or at least within the boundaries of – the archdiocese of New Orleans who are not on its credibly accused roster. Those individuals have, however, landed on similar lists published by other dioceses or religious institutions across the country, according to the authors of the documents seen by the Guardian.

The memo’s authors found another four priests whom an archdiocesan advisory board found to be credibly accused yet were still omitted from any list.

And an additional 169 priests and deacons as well as four non-clerical workers acknowledged by the New Orleans archdiocese were named in abuse claims filed as part of the organization’s bankruptcy case. (Another 34 non-clerical workers were accused in the bankruptcy, but the archdiocese has apparently argued that they were not technically employed by the organization, and the disagreement hasn’t been litigated.)

The difference is stark between the sheer number of abuse complaints and those whom the organization has named on its credibly accused list, which has always made it a point to exclude non-ordained employees.

From the 310 Catholic priests, deacons and acknowledged non-clerical workers – living and dead – in the New Orleans area who appear on a suspected molester list or who are fully named in an abuse claim in bankruptcy court, the archdiocese has judged just 24.8% of them to be substantially accused.

Despite that figure, research cited by the National Sexual Violence Resource Center finds that just between 2% and 10% of sexual assault reports are “false”. The center has found that even those low rates are almost certainly inflated because some reporting agencies draw no distinction between a false report and one that lacks what they consider to be enough evidence to substantiate.

Experts say there is an immense difference between a report that is false and one that is not able to be proven as true.

Additionally, the memo reveals other numbers that were of concern to the document’s authors. They found evidence that the archdiocese had referred only 23 allegedly abusive clerics – as opposed to non-ordained employees – to law enforcement as of the beginning of 2022.

Such referrals have helped lead to convictions recently.

On 12 July, Patrick Wattigny – the former chaplain of a Catholic high school in the nearby Louisiana city of Slidell – pleaded guilty to molesting two minors whom he met through his work and received a five-year prison sentence.

Late last year, VM Wheeler III pleaded guilty to charges that he sexually abused a preteen boy two decades earlier, before his ordination as a deacon. Wheeler, who had agreed to serve five years of probation in exchange for his plea, died in April.

Also last year, former Catholic school teacher Brian Matherne – who pleaded guilty in 2000 to molesting 17 boys – was mistakenly released from prison early before questions from his victims and local media outlets prompted authorities to re-incarcerate him.

Nonetheless, most of those 23 clerics who were referred to law enforcement investigators have not been prosecuted, convicted or even listed as credibly accused.

Wheeler is not among those whom the archdiocese lists in the credibly accused list which it curates. Neither is Matherne, who is not an ordained clergyman.

The memo’s authors also make it a point to say that – by their calculations – the archdiocese waited an average of 17 years from first learning of clerical abuse complaints to the point where it referred any information about them to law enforcement.

The memo names at least four clergymen whom a predecessor of Aymond saw fit to report to two separate regional district attorney’s offices in 2002 for possible prosecution but who were omitted from the credibly accused list 16 years later. They have also been omitted from subsequent expansions of that list.

The New Orleans archdiocese’s bankruptcy remains pending.

The organization did not respond to questions from the Guardian, citing the bankruptcy’s confidentiality rules. But Aymond issued a statement that – in part – promised that the archdiocese “would continue to look for ways to strengthen programs” which the church has said are meant to protect both children and “vulnerable” adults.

He also said the archdiocese was meeting with clerical abuse survivors “to review and enhance … protocols for responding to allegations”.

After his administration struck 132 settlement agreements with clerical abuse claimants during a 10-year period beginning in 2010, Aymond wrote a letter to global Catholic leaders in the Vatican estimating that it would cost the archdiocese less than $7.5m to resolve the rest of its mounting liabilities through bankruptcy court.

But, as the local news outlet WWLTV recently reported, the archdiocese which Aymond has headed since 2009 has paid about $25m in bills to attorneys and consultants so far in the case. None of that money has gone to those who have filed unresolved abuse claims in the bankruptcy.

Adding to the frustration from many abuse survivors and their advocates is the fact that a top Aymond adviser earlier in the case testified in open court that the archdiocese did not need bankruptcy protection to remain financially solvent.

“If the archdiocese was not in bankruptcy, would it be solvent?” an attorney asked the organization’s chief financial officer, a priest named Patrick Carr, during that hearing.

“Yes,” Carr replied, according to a transcript of the hearing.

Yet Carr maintained that bankruptcy was the method that best positioned the archdiocese to fully pay off abuse victims and others owed by the organization. And Aymond echoed that in his recent statement to the Guardian.

“My focus is bringing the bankruptcy proceedings to their conclusion so that the survivors can be fairly compensated,” Aymond’s statement said. “I know that there is no amount of money that can bring healing to those who have been hurt. I only hope that my prayers and the pastoral support the survivors are able to receive will help them and bring them peace.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!